Few people could help us appreciate intersectionality more than Abbas Kardar.

Abbas Kardar is a pseudonym for an Ottawa resident who spoke to Xtra on the condition of anonymity. Kardar is Muslim, queer, gender fluid and uses the pronouns “they” and “their.” Their family emigrated from Pakistan to the United States when Kardar was 14. Life in small-town USA was hard.

“In high school I was bullied, my sister was bullied, and there was just general Islamophobia in the town,” they say. “It was hard for my parents to get a job, and I know it affected our immigration status a lot. We were denied immigration and our visa several times, and I know my parents had to spend a lot of resources and time to try to keep us in the US.”

Being called a terrorist because you’re Muslim isn’t an experience restricted to post-9/11, small-town America. Universalist Muslims, a not-for-profit organization, works to dispel anti-Muslim stereotypes while promoting peace and understanding. Shahla Khan Salter, the co-founder of Universalist Muslims, says Muslim youth, particularly those who are queer, often face oppression from multiple sources.

“I do get calls from queer Muslim youth, and they are in such incredible pain,” Khan Salter says. “They are having a very hard time with their parents and with a society that has a lot of bigotry towards Muslims.”

For Kardar, being queer felt overwhelming, but their uncle recommended reading about progressive Muslim scholars whose interpretations of the Quran embrace LGBT people. Kardar’s uncle never asked if his nephew was queer, but reading the books made a big difference.

“It wasn’t until I read those scholars and read those books that I started seeing that being Muslim and being queer weren’t exclusive,” Kardar says.

While the books helped, finding community took longer. Already targeted by xenophobia, racism and Islamophobia, Kardar didn’t feel safe talking about sexual orientation and gender identity during high school. Bullied at school and living in a home where homosexuality wasn’t accepted, they didn’t find support and community until university.

Mego Nerses, a mental health counsellor at the Centretown Community Health Centre, understands the power of community in breaking isolation. He says being a Syrian immigrant who is fluent in Arabic helps to establish a sense of trust with clients who are newcomers to Canada.

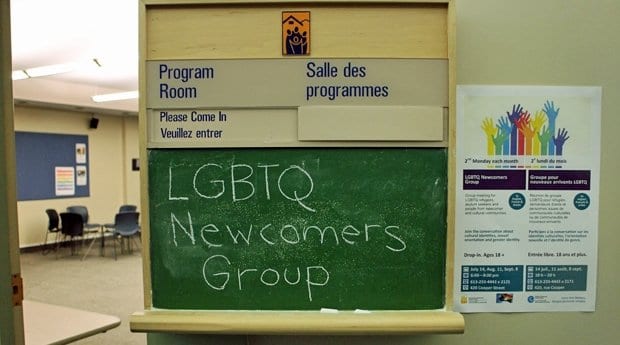

“For queer Muslims, what I’ve seen in my practice is a lot of isolation, a lot of barriers,” Nerses says. “That’s why we created the LGBTQ Newcomer Program, so we can start something. There’s so much need out there, and we need to get to people who are really isolated and reach out to them.”

The group, which meets on the second Monday of each month, is co-facilitated by Ernie Gibbs, a mental health counsellor for LGBT youth. Drop-in participants must be 18 or older, but individual and family counselling is available for LGBT youth 12 and up.

Kardar, who moved to Canada in 2008 and has lived in Ottawa since 2013, hasn’t been to a group meeting, but they applaud outreach initiatives like this. Another encouraging development is El-Tawhid Juma Circle’s “gender-equal and queer-friendly” mosques in Toronto and Vancouver. The group is expected to open a new mosque in Halifax.

Creating safe spaces and encouraging open, respectful dialogue will help queer Muslim youth, Nerses says, but he stresses that everyone has unique challenges created by their family dynamic, culture, language, beliefs and needs. As well, many Muslim newcomers face immigration issues, a topic the newcomers group discusses, he says.

Kardar, who is in their late 20s, isn’t yet out to their parents, adding that immigration issues complicate the already intimidating situation of coming out. “My family is still undocumented in the US, so I guess part of the reason why I haven’t [come out] is because they have — I don’t want to say bigger things to worry about — but more immediate things to worry about.”

Being undocumented, their parents can’t travel to Canada, and Kardar, who came to Canada on a student visa, can’t travel to the US. Deported from the US at age 25, Kardar can’t apply to return until age 35.

“It was a combination of being undocumented and the US government’s racial profiling against Muslim immigrants post-9/11,” Kardar says of being deported. “After a couple of years fighting them in court, I ended up being deported by the government.”

Kardar spoke to Xtra on condition of anonymity partly because they don’t want readers to see one person’s experience as a template of being young, queer and Muslim.

“I didn’t want to put my name out there in a place where I might collectively represent something because I don’t think that voice necessarily exists,” Kardar says. “But there’s a multitude of voices, and I’d like to be one of those voices.”

LGBTQ Newcomers Group

Mon, Sept 8, 6–8pm

Centretown Community Health Centre

420 Cooper St, Ottawa

613-233-4443

In English, French & Arabic

centretownchc.org

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra