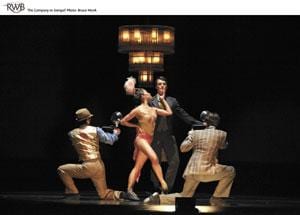

Harrison James dances in Svengali. Credit: David Cooper nac-cna.ca

Credit: David Cooper nac-cna.ca

Despite what you may hear in the conservative media, having a domineering mother is not what makes you gay. Royal Winnipeg Ballet soloist Harrison James knows that for a fact.

“My mother was great, not overbearing at all and totally supportive,” he says. “Growing up in ballet you see a lot of kids trying hard to make their parents proud but unable to meet impossible standards. I feel lucky to have come from an environment where I was supported in doing what I loved but in a way that meant I enjoyed it.”

James will have to mine memories of other people’s militant stage moms to tackle the title role in Svengali, a man hell-bent on manipulating women to compensate for his iron-fisted matriarch, reimagined here as a stern ballet mistress.

The role is an exciting turn, since James joined the company only a year and half ago after emigrating from New Zealand by way of San Francisco. As anyone who has seen Black Swan knows, the internal politics of ballet companies can be fierce, with steadfast hierarchies when it comes to the assignment of roles. James isn’t considered a principal dancer (a company’s senior artists who typically take the juiciest parts), so winning the role is a huge opportunity.

“It’s a great chance for me to prove my worth to the company with such a choice part,” he says. “It’s a quite emotional and psychologically complex character, which makes it a big challenge. These are the kinds of roles you live for as a dancer.”

Staged by choreographer Marc Godden, the piece is a sort of adaptation of an adaptation, based originally on French writer George du Maurier’s hugely popular 1894 novel Trilby, then remade as a film by Winnipeg native Guy Maddin. (The work will eventually become a dance film, the company’s second; it did the same with 1998’s hugely successful Dracula.)

As a young man, Svengali begins practising hypnosis and, in retaliation for his mother’s persistent desire to malign him, woos one of her students into burning herself on the ballet studio’s wood stove. After fleeing home, he meets Trilby (Amanda Green), a maiden of the streets going nowhere fast. Using his newfound knack for mind control, he turns her into a world-class dancer, the catch being she can perform only while under his spell.

Numerous textual liberties have been taken: the action has been relocated to pre-Nazi Weimar Germany from Paris; Trilby’s forcibly given talent has been changed from singing to dancing; and Svengali’s Jewish identity (the original work is often seen as deeply anti-Semitic) has been removed. But questions around gender roles and societal expectations of women remain.

“Svengali’s mother is obsessed with superficial ideas of perfection, which he takes on, as much as he wants to rebel against her,” James says. “He tries to change Trilby into his version of a perfect woman, even though it’s not something she wants. It illustrates how problematic moralities can be passed from one generation to another, even when we think they’re not.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra