From 1994 to 1998, I made a film about Paul Bowles, Let It Come Down, which was released last year. While I was editing the film – spending months with a virtual Bowles in the edit room, trying to find the man in all of that footage – I was afraid he would die before I had finished and not see it. I was also, almost equally, afraid to take it to him and face his reaction.

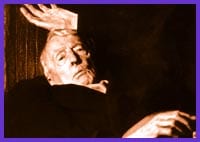

I travelled to Tangier last November with a VHS cassette and the screening met with grudging approval, much to my surprise and relief. It was the last time we saw each other. But somehow, the film’s ongoing life in the world required the thread which stretched back to that frail, elegant figure who lay in bed in a cluttered room, smoking kif and lost in reflection.

When I was told of his death, reportedly from a heart attack, the severed thread created an identity crisis: The film’s content underwent a shift from historical record to something resembling an elegy.

Now, when I reread the interview or watch specific scenes, they are charged with a different meaning, have a different weight. But those of us who loved or admired Bowles would be utterly misguided to succumb to the maudlin: He eschewed sentimentality about death, unwaveringly, right up until he faced it himself.

What follows is an excerpt from my interview with him.

JENNIFER BAICHWAL: Are you afraid of death?

PAUL BOWLES: No. Afraid of it? I’m afraid of suffering, yes. But not of losing consciousness forever. No. How can you be? You may regret the idea of dying – you probably would wish that you could go on and see what happened tomorrow. But that’s impossible, it’s written that you should die today, and that’s that. I feel there’s no such thing as death.

BAICHWAL: What do you mean, “There’s no such thing as death”?

BOWLES: Well, one can’t be dead. I think that’s what I mean. It’s impossible to be dead, because to be is quite the opposite of death.

BAICHWAL: That’s true. If death is nothing, then you can’t be it.

BOWLES: That’s right.

BAICHWAL: But you can be dead for other people. When you die, your death has enormous repercussions for those who love you, who know you.

BOWLES: You don’t think about that. You’re dead!

BAICHWAL: They think about it.

BOWLES: But you don’t care, you’re dead. I’ve always agreed with Gertrude Stein, who said once in her inimitable way, “When a Jew dies, he’s dead.” And that means a lot. ‘Cause when a Christian dies, he’s not dead. And when a Muslim dies, he’s not dead. But when a Jew dies, he’s dead. And I think that’s a very sensible remark and a very religious remark.

BAICHWAL: And you think the same? When you die, that’s it.

BOWLES: Well of course. Naturally. How can one think anything else and subscribe to logic? Isn’t death logical?

BAICHWAL: Yes, but there is a part of us that goes on every day as though we are immortal.

BOWLES: As long as we’re alive. But when we stop being alive, that doesn’t go on, does it?

BAICHWAL: Well, who knows? Maybe that part continues. If we were conscious of our mortality all the time, we’d be unable to achieve anything. We’d just sit around thinking about death. So we go on without the consciousness of our death.

BOWLES: Well, I don’t know what that proves, beyond what’s in the consciousness. People think of immortality as a goal to be attained. Why not? I mean, to think of it that way is fine. But to believe it will be that way… that’s something else.

BAICHWAL: What do you think you have to do to achieve the goal of immortality?

BOWLES: Well, it’s impossible, you can’t achieve it.

BAICHWAL: [Novelist William]Burroughs said that he thinks immortality is worth striving for.

BOWLES: But why?

BAICHWAL: Well, would you like to be alive for eternity?

BOWLES: Never! Awful idea. That’s what’s so good about life, that it comes to an end. That, one can approve of. The inevitability of its end is something that’s worth appreciating in life. The idea of being condemned to an eternal life is, I think, the idea of hell.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra