A new gay film from China. That’s not a phrase one hears very often, no matter how many film festivals (gay or otherwise) you might attend.

Occasionally, despite efforts by the Communist government, the rest of the world is afforded a rare glimpse into how gay men and lesbians live their lives in mainland China. Both the 1996 film East Palace, West Palace and the recent Man Man, Woman Woman were bold examinations of homosexuality in that country and were acclaimed for, among other things, the fact that they existed at all.

Now Hong Kong-based director Stanley Kwan ups the ante with Lan Yu, a frank, unflinching gay love story set in Beijing that makes its North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival.

“It’s true that it’s all but impossible to be openly gay in China,” says Kwan, “and that the issue remains more or less taboo in public discussions. But once you get past the surface reticence, you find that mainland Chinese gays are actually very confident and secure in their sense of their own sexuality.”

Along with Wong Kar-Wai (acclaimed for Happy Together), Stanley Kwan is widely considered to be one of the most original and inventive filmmakers working in Hong Kong today, evoking the glory days of Shanghai cinema of the 1930s and ’40s in his lush reworking of genre pictures. His earlier films, including Rouge, The Actress and Red Rose, White Rose, saw Kwan labeled as a director of “women’s pictures” for his focus on female protagonists and melodramatic stories.

That all changed with the 1996 release of Yang And Yin: Gender In Chinese Cinema. Commissioned by the British Film Institute to mark the centenary of cinema, the documentary was remarkable for two reasons. First, it was a groundbreaking examination of the way gender and sexuality have been represented in Chinese cinema (including the mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan), arguing that it had been freer and more inventive in portraying a range of sexualities than much of Western cinema. Second, it marked Kwan’s public acknowledgment of his homosexuality, revealed in the film during a conversation with his mother.

Uncomfortable being labeled a gay filmmaker – “I am more likely seen as a filmmaker who is also one of the few token gay men in Hong Kong,” he says – Kwan has nonetheless included gay themes and characters in his recent films Still Love You After All, Hold You Tight and The Island Tales. It is with Lan Yu though, that Kwan finally makes the “gay film” many of his fans have been waiting for.

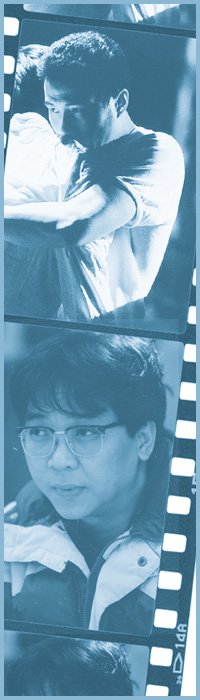

Lan Yu (newcomer Liu Ye) is a poor boy from the country, new to Beijing and desperate for money. Willing to prostitute himself so he can stay at university studying architecture, his first customer is Chen Handong (Hu Jun, who also starred in East Palace, West Palace) a rich businessman from an important family. After a night of intense passion that surprises them both, they begin a relationship that the older Handong considers a fling and Lan Yu believes to be much more.

Handong showers the younger man with gifts and money while Lan Yu wishes for the only thing he can’t have: Handong’s love. Over the ensuing decade, the two men break up, lose contact and reunite against a backdrop of political and social upheaval in China that includes the Jun 4, 1989 massacre in Tiananmen Square (where the demand for democracy ended in death), widespread government corruption and numerous twists of fate.

The story behind Lan Yu would make a great movie itself, a triumph-against-the-odds thriller. Shot in secret in Beijing without official clearance, the footage was smuggled out of China and the film had its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May. Kwan is understandably evasive (he still lives and works in Hong Kong) when asked about this, saying only: “I can’t tell you how or where we shot it, but it’s true that we needed to use some ingenuity.”

Considering that homosexuality still does not officially “exist” in China, the danger of shooting such a provocative film under the nose of the government must have been extraordinary.

The film is based on the Internet novel Beijing Story, which was published anonymously in 1996 and spread like wildfire among China’s gay population, becoming the most widely read text ever to emerge from the underground there.

The novel is a sexually explicit, unapologetic gay love story and unlike anything that had ever been publicly available in China before. Its author adopted the ironic moniker Beijing Comrade (the Chinese word for comrade, “tongzhi,” having become a slang term meaning gay) and Beijing Story pioneered the idea of publishing illicit Chinese fiction on the Internet, setting a precedent that has since been copied by others.

Kwan became aware of the novel when Zhang Yongning (who plays Handong’s brother-in-law in the film) brought it to his attention. He wasn’t sold on it at first, finding himself “mildly shocked by the novel’s explicitness about gay love-making, and not in any way a great piece of writing.”

Upon reading it again, however, Kwan began to relate to the novel, seeing some of his feelings about his own relationship reflected in the characters.

Along with screenwriter and frequent collaborator Jimmy Ngai, Kwan set out to, in his words “tell a story of two men who start a relationship on a sexual/ materialistic basis that, as time goes by, transforms itself into one filled with love.”

Kwan also faced accusations that he was an outsider telling a story that is very specific to Beijing, and he recognizes that “the original author may not be too satisfied with what I’ve done in the film – the author uses the central relationship to reflect 10 years of changes in society and social attitudes.”

He admits that “if a mainland director had made the film, probably that social dimension would have survived quite strongly,” but says that for him, Lan Yu “is not a film that deals with issues but a film that tells a simple story of two men who have no control over their ambivalent environment.”

But Kwan does not ignore the political context of Chinese society, and is able to convey very different aspects of life in China through the two lead characters.

Handong is a product of traditional China. From a respected family, he regards his male lovers as “playmates” and has no doubt that he will marry and have children as all “mature” men must. In business, he is a product of the Communist system, involved in bribery and illegal activities that are ignored by the government as long as it benefits from them.

In contrast, Lan Yu represents a more modern view of Beijing – open, honest and willing to live his life as a gay man. His integrity is reflected in his choice of career. As an architect, he can literally redesign and rebuild China.

It is in his presentation of the Tiananmen Square massacre that Kwan demonstrates his subtlety and skill as a filmmaker. There are no crowd scenes or archival news footage of tanks rolling through the square. Instead, in the privacy of their room, Handong tightly holds Lan Yu while the younger man sobs uncontrollably, trying to understand what just happened and how it could have ended so badly. Lan Yu’s tears are “an offering to all those who died that night,” Kwan says simply.

Lan Yu is also a risky venture for the actors involved. After all, they remain in China and are the public faces of the film. “To say the least, I have nothing but the utmost appreciation and gratitude for both Liu Ye and Hu Jun,” says Kwan, “offering their best in dealing with the circumstances and consequences.”

What those consequences are, he doesn’t say.

Despite the pressure, the actor’s performances are exceptional. Hu Jun plays Handong as an arrogant man of privilege, refusing to soften his characters edge’s to make him more likable, while Liu Ye imbues Lan Yu with a wounded intensity that is magnetic. The scene where the two lovers break up after Handong decides he must marry a woman is a superb example of minimal acting yielding maximum emotional impact.

Kwan attributes their performances to chemistry, professionalism and what he calls a mainland Chinese approach to acting. “They take the characters they play as fictional and don’t make connections between the fiction and their own lives.”

This approach is directly opposite to the live-your-character method acting favoured in Hollywood. Kwan contrasts his mainland cast against actors in Hong Kong, saying “Hong Kong actors are almost neurotically concerned about their public images; most would be terrified about playing a gay role in case their fans would get the idea that they’re really gay.”

As for being one of the few openly gay artists in Hong Kong, Kwan takes it in stride, noting that since he came out, “stud actors are more prompt to flirt with me, socially speaking.”

Lan Yu screens on Wed, Sep 12, 6:15pm, Cumberland 2 (159 Cumberland); and Fri, Sep 14, 6:45pm, Varsity 3 (55 Bloor W). Tickets are $13.

TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL.

$13-$23.55.

Thu, Sep 6-Sep 15.

Various locations.

(416) 968-FILM.

www.e.bell.ca.filmfest/2001/.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra