A Mar 19 ruling from Quebec’s Court Of Appeal means that 75 percent of queer Canadians now have the right to marry in their own province.

The unanimous decision means same-sex wedding applications can be processed immediately – although the province requires a 20-day waiting period before the actual ceremony.

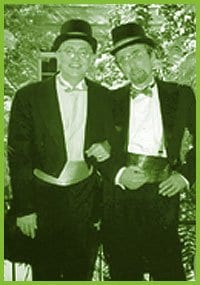

Michael Hendricks and René Leboeuf, the couple at the centre of the case, were ecstatic with the decision and shocked that nothing else seems to be standing in the way of them finally marrying after more than 30 years together.

“We were beginning to wonder whether it would be the funeral chapel or the marriage chapel that we make it to first,” jokes Hendricks, 62.

Sitting in a dingy little courtroom with their lawyer, Colin Irving, the couple couldn’t believe that the decision was so positive. Hendricks says they expected anything but a simple quash.

“First of all, we didn’t believe what happened. If anything can go wrong it will go wrong in the Hendricks-Leboeuf case. If anything gets fucked up it will get fucked up.

“Our second reaction was: Now we have to actually do it after talking about it for five and a half years.”

The decision upheld a September 2002 decision by Superior Court Of Quebec Justice Louise Lemelin, tossing aside the request to appeal by a coalition of religious organizations which wanted that positive ruling overturned. The feds gave up their appeal in the midst of similar rulings last summer in Ontario and British Columbia.

“They agreed with our lawyer that the religious groups did not have adequate standing as a representative of public interest,” says Hendricks. “There were no grounds to appeal once the federal government was gone.”

While Lemelin’s decision delayed implementation of same-sex marriage until September 2004, the Court Of Appeal granted it immediately.

Armed with a court order, and accompanied by their lawyer, Hendricks and Leboeuf, 48, headed over to the civil marriage office that afternoon to pick up their licence. They took a number, 63, and waited in line for their chance to apply. After being rejected in 1998 and again in 2000, the third time was the charm and the licence was approved.

“We were accepted as absolutely equal including the 20-day waiting period,” Hendricks adds. “That’s the irony of it. We asked for exceptional treatment and we didn’t get it. We didn’t win that one little thing.”

At first. The couple later received a waiver of the standard 20-day waiting period and scheduled their wedding for Thu, Apr 1, a date that commemorates the first civil marriage between two persons of the same sex in the Netherlands in 2001.

“Everybody [family and friends] is just delighted. They know the strain and how much it cost us financially. You all got married and we couldn’t. Now we’ll shut up about it and get on with our lives.”

Hendricks ponders the irony of a new class of couples who now have the legalized right to marry in Quebec, Ontario and British Columbia, but for whom no divorce laws have been written.

“We’re the only people who are married, literally, for better or worse, for richer or poorer, ’til death do us part. No one can get unhitched until they change the Divorce Act.”

He thinks it will be interesting to see what happens over the next month as the 20-day waiting period is reached. Already he knows of couples who said they would never get married but who are now considering it, given the change in legal status.

“We’ll find out how many homos are getting married in two months.”

As for the rest of Canada – the Supreme Court will rule on the constitutionality of same-sex marriage next fall, after which Prime Minister Paul Martin has promised a free vote in Parliament.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra