“Please tell me I matter.” Poignant and honest words from the play Pterodactyls, written by Nicky Silver. This blackest of comedies anchors its biting wit in the universal quest for approval, with exhilarating and riveting results. Opening Fri, Jun 4 in the mainspace at Tarragon Theatre, Pterodactyls is set to explode onto the Toronto scene with a hilarious vengeance reminiscent of Brad Fraser’s finer theatrical moments.

Like Fraser and Unidentified Human Remains And The True Nature Of Love, Silver plumbs the depths of destructive behaviour in Pterodactyls, examining the corrosive roots of personal history in an attempt to illuminate the despicable actions of frequently unsympathetic people.

Silver has written an unlikable but understandable central character, Todd Duncan (played by Ross McKenzie) who returns home and announces he has AIDS. We are introduced to members of Todd’s WASP family, each with their own distinct mechanism of dysfunction: his neurotic hypochondriac sister Emma (Charlotte Gowdy), her fragile fiancé Tommy (Paul Dunn) and the emotionally corrupt parents Grace and Arthur (played by Sarah Dodd and Don Allison).

Todd acts as a merciless sword, tearing deep into the lies surrounding his family. As the play unfolds, we are drawn into his steely manipulation of the other characters, as he challenges them to examine the truths behind their dysfunctional behaviour. With chilling calculation, he seduces his sister’s fiancé and purposefully breaks his heart. Todd’s callous treatment of Tommy is hard to experience, but illustrates perfectly his own inability to connect emotionally with others.

While his family reels under his Machiavellian actions, Todd remains detached and analytical – far more intent on piecing together some bones he has unearthed in the back yard. This particular metaphor is played through to an amazing revelation, as each character’s skeletons emerge from the closet.

“I think it’s a fantastic part to play,” says McKenzie. “I’m having the time of my life.” He readily acknowledges that Todd is a difficult character, but relishes the element he brings to the text. “It’s all about truth, and how things can go horribly wrong when you don’t face or speak it,” he says. McKenzie serves double duty as the play’s co-producer; he recently produced the sold-out run of Seven Stories at Theatre Passe Muraille.

The action in Pterodactyls starts with Todd’s sister Emma returning home with Tommy to inform her family of their impending marriage. Fighting to be acknowledged by her whirlwind of a mother, while avoiding her physically effusive father, Emma revels in imagined diseases and afflictions designed to attract attention. As her own relationship spirals downwards, Emma withdraws further from reality – perhaps the most obvious victim of abuse in the play.

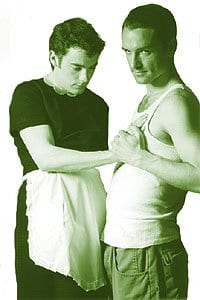

Orphaned, poor and homeless, her fiancé Tommy is given the recently departed maid’s job in order to secure housing and employment – lacey apron and all. He’s a study of apologetic neediness, desperate to carve out a space for himself within this new family. Excelling in his new job, he takes great pride in contributing to the domestic scene, finally discovering a place where he feels a sense of belonging. Once seduced by the predatory Todd, the confused naïf falls desperately in love with him, and begins revealing his bleak upbringing.

“He’s looking to matter,” says Dunn, of his eager-to-please character. “But when he finds the love he’s looking for, he finds all the bravery in the world.” Dunn’s open and innocent face perfectly reflects Tommy’s child-like search for affection and security, and his surprise at the sexual awakening engendered by Todd.

A frequent feature of the Stratford Festival, Dunn is a respected playwright in his own right. Stratford’s Studio Theatre mounted a production of his play High-Gravel-Blind in 2002, and Theatre Direct produced his one-man show Boys in 2000.

Then there’s Grace Duncan. As matriarch and proverbial rich bitch, Grace boozes her way through a privileged life, determined to ignore the undercurrent of hostility rising to the surface of her “perfect” family. Her razor sharp one-liners are devastatingly witty, and do much to wilt the already erratic Emma. Grace is a sort of Martha Stewart doyenne, with loads of cash to further create an illusion of perfect domestic bliss. Her home reflects a ruthless attention to fine detail, and she directs that same unwavering resolve to commandeering her hapless daughter’s nuptials and her son’s anticipated funeral. “I love planning a party the occasion is piffle!”

Todd’s father, Arthur, longs to recapture his fantasy of father-son camaraderie, but dwells in a foggy fiction of baseball outings and friendly games of catch that never existed.

While avoiding the reality of his son’s sexuality and illness, Arthur still attempts to reach out to the resolutely distant Todd. His relationship with Emma is a murky one, with allusions of inappropriate affections and favouritism.

The great strength of the play is its uncompromising look at Todd’s motivations and manipulations. As playwright Silver puts it in the liner notes, “Todd is no more heroic than the other characters.” He is an enormously unlikable character, but intensely compelling to observe as he destroys the last vestiges of a fabricated and stunted childhood. Todd has not come home to die; he has returned to avenge and inform.

Though his acts occasionally seem cruel, we are allowed glimpses into his tortured and raging soul. “There’s so much dysfunction underneath the surface,” says director Mathew Kutas. “They each have their denial mechanisms.” For Kutas, it’s all about taking responsibility for mistakes made, and he likens Grace and Arthur’s emotional stone-walling to the parents of the Columbine shooters. “They [the shooters’ parents] didn’t change their names, and they live in the same town,” he says in disbelief. “They won’t take any responsibility for it.”

It’s this kind of deliberate denial that Pterodactyls examines and ultimately condemns. Each character is forced to confront their own culpability in damaging each other and, in doing so, find their own way of escaping the vicious cycle. “At the end of it, they’re not terribly likable,” says Kutas, “but they’re also not wrong they’re just messy.”

Silver manages to be provocative and surprisingly funny, without being overly maudlin. As Kutas says: “It has this absurd comedy aspect at times, and then this underneath, straight-ahead drama.”

The set, by Laird MacDonald, is a static sixth character in the play. It evolves throughout the show, reflecting the changes in the family as secrets are excavated and hearts are broken. Using found objects, MacDonald has created an incredible focal point for the plot – but I won’t spoil the surprise.

Evan Tsitsias is co-producing Pterodactyls, alongside McKenzie’s Shakti production company. Tsitsias brought Pterodactyls to Kutas and McKenzie, after having seen a smaller production back in the early 1990s. The 1993 Broadway premiere garnered raves and marked a break-out for the playwright; it went on to numerous subsequent productions and prizes. Follow-up plays by Silver include Raised In Captivity and Free Will And Wanton Lust.

“I think Toronto’s ready for these kinds of different shows,” says Tsitsias, “this show can be very commercial, though some people think it can be sort of taboo.” He and Kutas have worked together previously on the play Burn This, and he’s pleased with the easy collaboration between the three. “We’re all coming from the same place on this,” says Tsitsias.

While often bleak, Pterodactyls is full of scathing wit and survivalist humour – those moments of hilarity we find even in the darkest human struggle. In revealing the troubling truths behind every front door, Kutas reminds us that, “What you see outside the house is never what you see inside the house – ever.”

PTERODACTYLS.

$28. Fri, Jun 4-20.

Tarragon Theatre.

30 Bridgman Ave.

(416) 531-1827.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra