When George W Bush recently accepted the Republican nomination for reelection many viewers were troubled by his convention speech. Violently opposed to abortion, determined to prevent gay marriages, raging against science that does not meet religious tests, placing his trust in churches to administer social welfare, Bush’s speech aimed to please the fundamentalist Christians in today’s Republican Party.

Surely among those watching him speak in New York were many readers of Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale, a futuristic story which now seems far too close for comfort.

Atwood’s book concerns a time in the near future after a revolutionary version of Christian fundamentalism has been imposed on the United States. At a time of social unrest and environmental degradation a determined group wrested power from the government, partly by using the fear of Islamic terrorism – an eerie forecast of present day reality.

The society described in The Handmaid’s Tale is one whose main goal is the dependant status of women. Restrictions on clothing, the deliberate denial of schooling, literacy skills and freedom of movement, and above all a pervasive and horrific system of sexual subjugation: These are the main functions of government in Atwood’s Republic Of Gilead.

The same cataclysmic events that recently have aided the religious right in the US have made others more aware of the denial of women’s freedoms in countries such as Afghanistan, Iran and Saudi Arabia. Atwood’s vision of life in a future American gulag for women makes her novel required reading for informed citizens of the world.

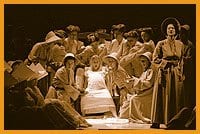

Opening in Toronto this month is an operatic version of the novel – the Canadian Opera Company is mounting The Handmaid’s Tale by Danish composer Poul Ruders and British librettist Paul Bentley. The opera was first produced for the Royal Danish Opera in Copenhagen in 2000 to raves and has since been seen in London and Minneapolis. Opera companies have to plan years ahead, so by interesting happenstance, the COC finds itself bringing the opera to Toronto at an extraordinary moment in history.

Associate director Michael Walling made the point that most opera-goers should be pleased by the careful yet exciting way in which the ideas, characters and actions that make the novel such an important experience have been reproduced on stage.

Of course, in writing for the operatic stage, Bentley had to employ different storytelling methods from those that a novelist can use. In Atwood’s version, the world of the Handmaid and the horrors of Gilead are slowly revealed, layer by layer. “The authorial voice used by Atwood’s narrator gradually points us toward the truth,” says Walling. “On the stage, events have to have more immediate meaning.

“In an opera, the audience experiences the story emotionally, so plot details must be clear from the start.”

One simple example is the way in which Bentley’s libretto has an explanatory prologue to complement his version of Atwood’s epilogue. Also, in order to match the novel’s flashbacks, he has come up with the concept of doubling the title character – two singers who represent the Handmaid now and in a happier past (Canadian mezzos Stephanie Marshall and Krisztina Szabó). The two versions of the same character illustrate the fact that we become different people as we age and as our social contexts change. Walling says the duets between these two versions of the Handmaid show us, “How nothing is new, only time and places change.”

He is sure that Atwood readers will appreciate the highly literate nature of the libretto, which he thinks has skillfully retained the plain speaking style of the original; moreover, “Ruders’ music carefully underlines the simple conversational style of the libretto.” Other commentators have used terms like “sumptuous lyricism” “dramatic… with the instinct of great film music” and drawn comparisons to Verdi and Richard Strauss to describe the range of Ruders’ music.

Finally, Walling points out how this highly sophisticated production uses colour to mark off the various members of society by the costumes they wear. “This is a society codified by colour, the costumes illustrate the hierarchies of the designed world of Gilead.”

The Handmaid’s Tale promises to change the minds of all those who decry opera as an out-of-touch art form. While Hollywood and the TV networks feed us jingoistic pablum, the COC is making controversial art out of today’s headlines.

* Beginning Sat, Sep 25, the COC is also presenting Donizetti’s story of love, power and madness in the Scottish highlands, Lucia di Lammermoor starring soprano Marina Mescheriakova (who was an amazing Norma in 1998 with COC).

$18 to $29 tix available for those aged 18 to 29.

THE HANDMAID’S TALE.

$40-$75. 7:30pm. Thu, Sep 23, 29, Oct 1, 5 & 9.

2pm. Sep 26.

Hummingbird Centre.

1 Front St E.

(416) 872-2262.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra