Mattilda B Sycamore. Credit: James Loewen

Credit: James Loewen

Mattilda B Sycamore thinks it’s time for an intervention.

Gay culture has become obsessed with normalcy, sanitized by assimilation and increasingly soulless, Sycamore says.

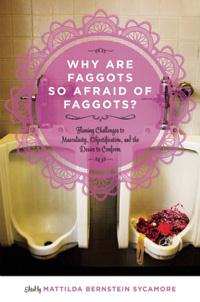

For a community founded by desire, this decline is particularly discouraging. “Desire is what started us — in terms of our love and our community building and our visions of intimacy,” says the editor of the new anthology Why Are Faggots So Afraid of Faggots?

Not to mention the desire “for full self-expression” in a world that often wants gay men to simply disappear. “There was a sense of communal struggle,” Sycamore says, especially in the 1990s, when being a gay man meant being surrounded by death.

But that struggle has since been muted by shifting desires.

“The nature of the gay movement has made desire into a dead end,” Sycamore says. “The desire just means buy this cocktail, wear these clothes, go to these bars, look like this — it’s all about creating a consumer identity.”

How could our desire have veered so off-track?

Sycamore blames the desire itself.

“Desire is what brought us to this sort of gay culture that either is obsessed with normalcy at any cost or this sort of close-the-blinds . . . lack of accountability or communal care,” she says.

“It’s now about fighting for the right to kill or get hitched,” she says, referring to the gay marriage battles and the push to end the US military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy. “I think there was a little more space in the early ’90s for flamboyance and for challenging political decisions. In San Francisco, there is a history of radical alternatives to community, family and sexuality. And since then, those cultures [and radical ideas] have been marginalized.”

Today’s focus, she argues, is shaped by mainstream ideas of family and marriage. These ideals have become so dominant that there is no room for any alternative.

“Now, you turn on the TV and you see vapid, hyper-consumer, pointless representations of gay identity, and you’re supposed to relate.”

For Sycamore, that’s worse than turning on the TV and seeing no gay representation at all.

“In the early ’90s, gay identity was represented by straight homophobic representations, but now we have gay people articulating straight, homophobic representations. Is that better? We’ve internalized the emptiness and violence of straight normalcy and we project that as our own goal and representations,” she says.

“The question for me is what would be an intervention for that kind of morass.”

As alarming to her as the sanitization of our healthy desire is the hyper-calculated, almost brutal, desire that smoulders underground, callous and unchecked.

Go into any chatroom and you’ll find that scorn has become “just a preference,” lack of respect is assumed, and lying is a given, Sycamore says.

“Under 30 only, no blacks or no Asians, or no femmes or fatties — these are universally articulated norms. In so many ways, our gay culture has become about who is excluded.”

As someone who grew up being called a “sissy” and a “faggot,” Sycamore knows what it’s like to feel excluded, particularly from an aggressively masculine world.

“What I find so tragic about mandatory masculinity in gay culture is that gay men are desperate to embrace the exact same thing that oppressed, and continues to oppress, so many faggots and sissies growing up — not to mention women, queers, trans people and yes, even straight men, the ones who can’t or aren’t willing to measure up either.”

Gay men are increasingly citing strong, hairy, tall, muscular men as their type and eschewing the wispier, willowier among us.

The modern gay man must be fit, wear the right clothes, know the right people and, of course, be “straight acting,” Sycamore says. “Anyone who doesn’t fit into these moulds falls into the margins.”

“So gay neighbourhoods are defined by who is not allowed,” she continues. “It’s sad because gay neighbourhoods started because gay men were trying to find ways to express themselves openly, where you can hold hands in public. And now, gay neighbourhoods are more based on — like San Francisco, where gay people have become part of the power structure. And you see gay people evicting people with AIDS, and gay people voting against the construction of a queer youth shelter . . .”

This hyper-consumer norm pervades gay male sexuality, as well, she believes. “In the sexual realm, it’s about what you can get, how you can get it, and throwing it in the trash. That norm, that hyper-consumer norm, is so dominant that it’s overwhelming.”

Sycamore would like to see gay culture re-broaden itself to welcome femininity and flamboyance — and risk.

Risk leads to growth, she says, whereas risk-aversion leads to stagnation. Or worse.

“What if the risks people are avoiding are the risk of femininity, or talking to someone who has HIV, or the risk of intergenerational contact?” she asks. “Those are the risks that are going to give us the answers to the questions that we need, to find the connection that we’re hoping for. Those are the risks that gay culture is afraid of.”

The possibility of a successful intervention lies in honest discussion, she believes.

“For me, the hope lies in opening up the possibility for an honest conversation that talks about the places where we failed, that talks about messiness, that talks about the problems, that talks about the places where our dreams become nightmares, the places where what we thought was going to lead to greater possibilities for intimacy or love or community . . . leads into walls.

“We’re never going to get anywhere else unless we can talk about these complicated spaces of failure, which also lead to more dreams,” Sycamore says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra