Most queers have a soft spot for Pflag — formerly Parents, Familes and Friends of Lesbians and Gays. Since the 1970s the organization has offered hope to homos who are alienated from their families, providing a resource to point struggling friends and family members toward for queer- positive support, and forming marching contingents at local Prides that brim with seemingly unconditional love.

But that fondness hasn’t necessarily translated into financial and volunteer support, particularly in urban centres.

“We’re certainly noticing that,” says Cherie MacLeod, executive director of Pflag Canada. “I think part of the challenge is a national challenge…. Pflag is largely still viewed as a gay group or a GLBT group or a parents group and so we’re looking to combat those stereotypes so that people see that no, we’re here for everyone.”

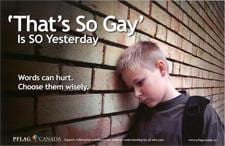

One of Pflag Canada’s current national projects is a poster campaign targeting young teenagers. The poster, which shows a picture of a preteen boy and includes the text “‘That’s so gay’ is so yesterday,” was designed to be used as a starting point for teachers to discuss all kinds of diversity.

“We’re working with teachers who are leading their students in creative writing assignments to tell this boy’s story,” says MacLeod. “They’re presenting this with the understanding that this boy is experiencing the pain of prejudice for a wide variety of reasons, and we have to work with teachers on this because even teachers don’t see this and understand that this child is not necessarily questioning…. This boy maybe struggling for a wide number of reasons including preferring a type of music that isn’t well supported and being called ‘gay’ because of it.”

MacLeod says the poster project, which Pflag is working to get into schools across the country with the resulting students’ stories to appear on the Pflag Canada website, goes above and beyond combating homophobia.

“It’s about understanding that this is not just about kids who are eventually going to come out themselves,” says MacLeod. “When I talk to kids I talk about, ‘What would your school look like if there were no issues around what you were supposed to be? Not just around homophobia and transphobia but how you were supposed to be.’ Without that risk involved with freedom of expression you would have kids with talents who would feel free to develop those talents. People would feel more comfortable taking risks of all sorts which would lead them to a greater awareness of who they are.

“I say, ‘If you look at that within your classroom then think of what that might look like in your school. Then think about what it would look like in your entire community… think of what Canada would be like.’ And the kids get it.”

At the same time Pflag hasn’t outgrown its peer-support roots, particularly in rural communities.

“In the rural communities we tend to be a catchall for everyone,” says MacLeod. “We see in those communities more of an integrated chapter dynamic where we have parents and we have allies — allies are very prominent in our rural communities — and we have LGBT people all working together. We’re finding that these chapters are really beginning to thrive because in that dynamic there’s a great opportunity for everyone to learn from each other.”

And they mean everyone. The Pflag philosophy, as described by MacLeod, is that all Canadians suffer from homophobia and transphobia and so all are entitled to Pflag’s support. That includes religious zealots who call up looking to argue the finer points of Leviticus.

“We had the dialogue on our board about who Pflag Canada supports and of course it came up, well, what about people who call quoting from religious scripture? Where do we fit them in with how do we allocate our time?” says MacLeod, “and that’s always a very challenging discussion… whenever you’re encountering someone who is bringing this belief that there’s an absolute truth out there and wanting you to atone or reckon with that belief system.

“I felt very strong that we needed to support these individuals, and someone said, ‘You know they could call anybody and have someone support how they feel and yet they’ve called Pflag… maybe at a subconscious level they want to be challenged on those issues, maybe they do want to have a dialogue.'”

With 70 chapters and contacts across the country MacLeod notes there’s still room to expand.

“Canada’s a big country. We have a lot of communities, we have vast numbers of people in huge spaces of geography that are not being served by anyone… and some of the stories coming out of those communities are just horrific, very upsetting, very frightening. Parents calling from communities of 5,000 people who are sure their child is the only gay child in the entire town and, ‘What’s going to happen to my kid?’ And that still seems to be the major point of fear for parents… ‘What’s going to become of my child? I’m so frightened for them.'”

The mother of two, MacLeod found Pflag after her own family was hit hard by homophobia.

“We had a cousin who was very close to our family,” says MacLeod. “In fact he had lived with us for a period when I was just a young girl. He was a very special young man in that he was really giving and always had time for everyone. He was my first mentor in my life where I was aware he was mentoring me.

MacLeod says that her cousin was desperately in need of support at the time that he came out to them — his partner was dying of AIDS.

“In our family there wasn’t even a discussion of whether we were going to support him. It was just so far removed from anything that we were thinking that it wasn’t even part of our consciousness. However in his family that was the main focus.”

After years of painful estrangement between the two families, MacLeod’s cousin became terminally ill.

“A couple of weeks before my cousin died of cancer… he asked my mother to call her sister and let her know that he was dying,” says MacLeod. “We had lived in this hope that there would be this reconciliation for nine years and when he authorized my mother to tell his mother that he was going to die we all expected that they would go to him and they didn’t… our hearts just broke. The entire family, we were a mess.”

When MacLeod’s aunt and uncle didn’t organize a funeral for their son, she says her family stepped in.

“The ashes did not go to his family they went to my mother and his partner brought them down from Ontario and we spread them at the gay beach,” she says. “It was beautiful in that we were this group of straight, dressed people walking through this gay nude beach to spread these ashes and say our goodbyes.”

Her cousin’s death — and his parents’ failure to reconcile with him — changed the course of MacLeod’s career.

“At that time in my life I was getting ready to send my four-year-old to school and looking at what I was going to do in my career,” recalls MacLeod, “and it was like this light opened up in the sky and the path lit up and it was calling.”

She says her commitment to Pflag and its work is just as strong today.

“Heart and soul, blood and bones, I’m still there.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra