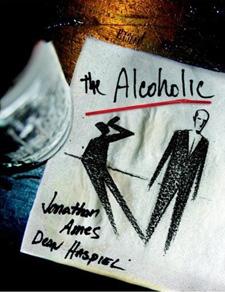

Jonathan Ames’s first novel, 1989’s I Pass Like Night, spurred no less a luminary than Philip Roth to call him a cross between Jean Genet and Holden Caulfield. His latest, a foray into graphic fiction, tops Ames’s 20-year reputation as an utterly candid author of the naked self. Cover blurbs from noted authors ramp up the adjectival competition, calling the book hilarious, wrenching, brilliant, enthralling, awesome, devastating and (from Bret Easton Ellis) “pitilessly funny and often horrifying.”

Ames’s voice, whether pitched as fiction or in the real-life tales of his New York Press columns, reads like personal revelation. This inspired collaboration with artist Dean Haspiel kicks off with a literally seminal teenage memory. Jonathan A and his friend Sal live in a small New Jersey town in 1979. They have been inseparable best buds since they were toddlers. At 15 both are sporty but semi-nerdy and still helplessly stuck on each other in a boyish bond that has kept them well outside the usual erotic marketplace of adolescence. Introduced to alcohol, they quickly become hooked on getting blasted every weekend — always with each other. We know where this is headed, but Ames and Haspiel’s magical words-and-pix synthesis makes the drunken sexual initiation and its painful aftermath feel completely new and incredibly touching.

Haspiel’s rendering of facial expressions and body language is uncannily expressive. It seems to go to the heart of what each guy is feeling, with a freeze-frame authenticity that film would need an entire scene to express. The morning after the consummation when Sal says, “Let’s never talk about it again,” the tortured evasion in his face and the acquiescent hurt in Jonathan’s is heartbreaking. You see a future of unspoken regret for a love that could have been. The pinprick from jaded tear ducts, over a comic-book image, was definitely a first for me.

Jonathan tells his story in retrospect, ranging back over his life from the vantage point of a midlife bender triggered by his first drink in 13 years. Ames’s story is not just illustrated by Haspiel’s images, but is actually driven forward in part by the dynamism of the drawings. Past and present merge and split off from each other with the help of literal splits and time-bending merges in the images. Nagging memory, as seen through the surreal lens of a dozen drinks, is stunningly represented.

The surface story shows Jonathan making a visible “success” of himself (graduating from Yale, moving to Manhattan, having casual girlfriends) while his inner voice remains all about the desperate teen, a boozer by night and whiz kid by day, still without a solid sense of self, still wondering what happened with him and Sal.

After six years of no contact, thinking all along that Sal hates him, Jonathan hears that he’s in New York. He looks up Sal’s number and they meet. We learn that Sal is now openly gay and broke off contact because he was sure Jonathan was straight and he didn’t want to “wreck” Jonathan by affirming his love. It’s a reconciliation of sorts, but the spinoff is just more complication between them. It’s clear the old bond can’t be rekindled.

Is Jonathan straight, bi, gay or what? One of the virtues of the book is that it doesn’t belabour these questions. Jonathan’s orientation takes a back seat to his basic, deeper issues of reclusiveness and loss. He’s never been a social gadfly, and he’s never had a love like the one he had for Sal. The purity of their bond is impossible for him to forget. A whirlwind romance with a hot young gal makes him briefly giddy with the love-and-sex combo he’s never had, but it fizzles when she moves to the west coast and stops returning his calls.

Meanwhile we watch him drive a cab for a living as he begins to build a career as a writer. He endures the loss of his parents. The moment when he must clear out their clothing from the family home is intensely moving. Working through his grief, he reconnects with his one remaining relative, Aunt Sadie. Their chatty visits at her apartment grow into an enduring friendship. By now we’ve reached the summer of 2001. With millions of New Yorkers, Jonathan finds his personal traumas subsumed by the horrors of 9/11 — but when the dust settles and the public memorials fade from calendars, the personal hurts remain.

This being a review, I’m supposed to list some flaws. I can’t find any worth mentioning. The story consistently achieves what the finest storytelling always does: It links your memories and emotions intimately with the world of a stranger, and in the process you know yourself better.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra