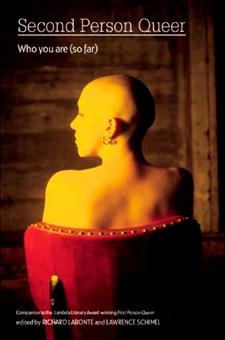

In 2007 we were treated to a delightfully eclectic and candid anthology, First Person Queer, offering intimate queer voices drawn from pretty much every personal camp and socio-political niche. It remains an essential document of in-your-face diversity. Editors Richard Labonté and Lawrence Schimel now offer the inevitable sequel, Second Person Queer, shifting the tone from soul-baring personal “I” to the more challenging — and more oracular — “you.”

Browse through the author bios and you’ll find about an even mix of US and Canadian writers, with a soupçon of off-continent voices. Settle to reading and the flood of queer identities quickly negates borders and national distinctions.

“Dear newly bisexual gay kid,” begins Daniel Allen Cox’s feisty defence of muff-diving fags and cock-loving dykes. “It sucks, you think to yourself, that someone would have to come out twice in one lifetime.” The worst of it, he notes, are the queer friends who think you’ve embraced the enemy, closely followed by “the gloating parents” celebrating your return to normalcy. “You fled the small-town nightmare a queer and came riding back a corrected heterosexual.” Closing advice: “Never issue a statement. The trick is to keep them guessing.”

Like many here, Stacia Seaman goes for the how-to approach. She advises the shy “visible femme” in a bar full of unimpressed butches, “You’ve got the power here. Use it.” The lesson in confident cruising is bare-bones motivational, spun with some evocative details: “the faded outline of a wallet in the back pocket, the black Harley boots… the faint scent of motor oil.”

Clarence Wong’s essay on his first (highly acrobatic) fisting experience ought to be required reading for any who imagine fisting to be a kind of consensual torture. Maybe those who deeply know its pleasures are the best teachers.

Roz Kaveney addresses a letter to her trans “brothers and sisters in hiding.” At issue are the “stealth” lives of women who bury the male part of their past (or present) by building lives of cookie-cutter suburban femininity. Her point that such denial only hampers the trans-lib cause seems right on the mark, but the second-person voice here comes across as bit of a harangue, the “you” all accusation. It demonstrates the built-in weakness of this editorial gambit: Writers are forced into the role of tough-talking life coach or advice columnist, while readers encounter sermons and judgments that have the tilt of personal criticism, regardless of whether it applies to them.

Do the words “ze” and “hir” mean anything to you? If not, you’d better update your gender jargon. S Bear Bergman lets us know in hir bio that ze lives with hir fiancé. Agreed, we must shed oppressive gender categories, but how many readers, queer or not, can penetrate the code? It doesn’t matter what Bergman’s gender identity is. What matters is that ze assumes we’re already inside the “ze” and “hir” language loop.

Ze indicates that hir spouse-to-be is a guy — otherwise he’d be a “fiancée,” sporting the girly extra “e.” So we’ve got a mix of both hidden and revealed gender, plus an open advertisement for old-fashioned marriage categories. Is all of this a deliberate layering of ironies? It feels more like gobbledygook, especially when placed next to Bergman’s essay, a forthright and gently touching apology from a trans child to a loving mother whose conventional expectations were dashed.

Maybe the sort of gender label-swap we can all relate to is a girl named Andy. We encounter exactly this in Sean Michael Law’s piece of advice to 13-year-old Andy, his daughter, who has just announced she’s bi. Law, like some other contributors, finds a way to sneak in the “I,” telling a story of how he taught himself to play the piano without recourse to standard theory or pedantic teachers. Andy, he implies, will have to dance to her own music, and not bow to pressures of convention. Generally it’s the “I” stories here that pull you inside, while the “you” ones tend to come off as pushy or simply unforthcoming, the writers’ personalities obscured by all the pointing at others.

Sky Gilbert’s how-to piece offers brisk wisdom on the ways to achieve total slut fulfillment — and still snare a life partner. “Two sluts are often a perfectly matched set, as long as they’re completely honest with each other. (If people tell you sluts never have partners, it’s because they’re jealous that you’re getting so much sex, and want to see you suffer.)” Gilbert matches erotic voracity with smartly pitched tips on staying safe and sane.

Viet Dinh movingly addresses his own community: young Asian men who must learn to negotiate both the seductions and rejections of insensitive or outright racist white guys. We learn that the blunt “Sorry, I’m just not into Asians,” is all-too common. Against such oblivious hurtfulness, the jowly legions of “rice queens” are seen almost as a blessing: “It’s nice to be desired… even if Edward Said rolls in his grave when he sees you together.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra