UNDETERRED. Tatou, Eva, Gogo at an activist gathering in Copenhagen last week (pictures are printed with permission and pseudonyms are used to ensure the safety of the activists). Credit: Ariel Troster photo

Just one day after participating in the Outgames human rights conference in Copenhagen, Denmark, a group of Chinese lesbian activists got the news that the magazine they publish had been raided and all of the copies had been confiscated by the Beijing police.

According to Eva, a bisexual activist from Beijing, queer people in China always find a way to circumvent government censors — even if it means exposing them to police raids or condemnation from other authority figures. She said that this most recent obstacle would not deter activists from spreading the word about queer human rights — even if it means converting the magazine to an online format using foreign servers.

Speaking at an activist gathering in Copenhagen, Eva, Tatou and Gogo (all pseudonyms) spoke about the burgeoning queer women’s movement in Beijing and the challenges associated with publishing an underground magazine in a country where such activities are closely monitored and censored.

Gathering in one of Copenhagen’s oldest squats called “The People’s House” last Thursday, the three women were taking part in a free human rights gathering following the main Outgames human rights conference.

The alternative gathering was organized by Danish queer activists, to protest against the fact that the main conference cost hundreds of dollars and was largely inaccessible to the local community. It also gave international delegates a chance to engage more deeply with local activists, mapping out strategies for how they might show solidarity across international borders.

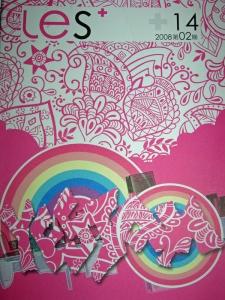

Eva, Tatou and Gogo spoke about Les Plus Magazine — a politics and sexuality journal that they have been publishing since 2005. The magazine — unlike officially sanctioned media — contains graphic descriptions of queer sexuality paired with provocative photos and political analysis.

Until last week, their primary method of distribution was through the Beijing LGBT Centre. Since the majority of the copies have now been seized, the women will have to figure out how to continue publication under more intense scrutiny.

But Chinese queers are used to getting creative.

“We cannot just parade on the streets and ask for our rights,” said Eva.

According to Eva, the gay, lesbian and transgender rights movement in China is still in its early stages and must use innovative strategies to get their message across.

Speaking over snacks and coffee prepared by local volunteers, Eva described the development of the first wave of open gay activism in China. From her description, the community really started to develop in the late 1990s, with a small profusion of dating websites, largely featuring same-sex personal ads.

This led to a series of magazines and radio shows — all underground, none officially sanctioned by the government. This, combined with an injection of HIV/AIDS funding directed largely at gay men, led to the development of an underground queer network, based primarily in Beijing.

According to Eva, the lesbian scene really started in the late 1990s, after a British dyke moved to Beijing and started throwing house parties. At first, the parties focussed on socializing and sex, but participants soon began to collaborate on community projects. One major development was a lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans help and resource phone line. But as resources were increasingly directed toward gay men in the face of the AIDS crisis, queer women began organizing their own projects and activities. The first lesbian bar opened in Beijing in 2005 and queer women’s activism took off shortly afterwards.

This culminated in the organizing of a major lesbian activist training camp called “Lala Camp.” In 2007, the camp brought more than 100 lesbian, bisexual, transsexual and queer-identified women together to share their experiences and strategize resistance activities. According to Tatou, this included providing basic media training to the participants, in an effort to capture the oral history of the burgeoning queer women’s movement.

The Lala Camp was so successful in 2007, that they held four similar camps in different parts of the country in 2008, and plan to do the same this summer. Their goal is to include a completely new group of women each year, aiming to plant activist roots in different communities across China.

Before coming out as bisexual, Eva produced the first Chinese language version of the Vagina Monologues in China — that was in 2004, and a production has been mounted at Fudan University in Shanghai every year since. The university started a course on Homosexuality Studies two years after the first production of the Vagina Monologues — Eva sees this as a direct result of the students’ determination to stage the Eve Ensler’s famous play, with its frank depictions of sexuality.

While it’s illegal to depict homosexuality, violence or pornography in public spaces, Chinese queer activists have found ways to slyly pass on their message. For the last couple of years, they’ve handed out roses on Valentine’s Day, with the stems wrapped in gay rights pamphlets.

And according to Eva, activists are much more technologically adept than the official government censors. When the Chinese government blocked Facebook, she and her friends had the code to get back in within hours.

“We always manage to get our websites back up,” she said.

For more info, check out Queer Comrades — a Chinese website featuring a webcast on queer issues.

Queercomrades.com.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra