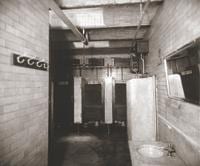

Allan Gardens lavatory, 1928. Credit: City of Toronto Archives

Urinals and compartments at Ward's Island lavatory, 1926. Credit: City of Toronto Archives

April 29, 1921. 10:45pm. A man enters the public washroom in Allan Gardens. According to the police constable patrolling the park that night, here’s what happened next: “I was looking into the lavatory. I saw Thomas S and another man, Harold F.

“Thomas S was sitting on the closet seat and peeping through a small hole in the partition. I saw Harold F put his penis to the hole and Thomas S commenced to suck it after a few minutes. I was watching. I went to the door of the lavatory, opened the closet door where Harold F was — he was pulling away from the hole and sitting back on the seat. I then arrested them.”

Long before Squirt and Grindr came along to guide us, men in Toronto discovered the potential of the lavatory as a site for sex. Lavatories were a central fixture in the sexual underworld of early 20th-century Toronto. I say “underworld” because several of Toronto’s early public lavatories were actually built belowground. From street level, you descended stairs into their dark, dank depths.

More commodious “comfort stations,” as they were sometimes called, could be found in the city’s central parks. Allan Gardens, as we’ve just seen, was popular. So, too, was Queen’s Park. But men also had sex in the washrooms of Union Station, the YMCA, and those in amusement areas such as Sunnyside and the Toronto Islands.

Men met up in a number of ways. Some found each other first on the street before repairing to a restroom. Other men waited with anxious perseverance inside the lavatory for another man to come into an adjacent stall. Once inside adjoining stalls, connected by a hole in the partition, men employed a variety of means to signal their interest. One might put his hand through the hole, or, as we learn from Henry B’s court case file, the other man “looked through a hole in [the] partition and then took his penis out and put it through the hole,” after which “he put his hand through the hole and grabbed my penis and took it in his mouth and sucked it.”

Another method was the straightforward proposition. In August 1919, Frank B recalled meeting Charles B when he came into the Central Y on College St. He “asked me to go to the toilet with him and he said he would give me a dollar. I went there and [he] started to open the front of my pants.” Unfortunately for Charles, the encounter ended at this point, and Charles found himself before the Police Court charged with attempting to procure Frank for an act of gross indecency. It’s not entirely clear from the case file whether Frank turned Charles in because he was shocked to discover Charles’s intentions or, more likely, because Charles failed to produce the promised $1, offering instead the less-than-acceptable sum of 50 cents.

Most often men ended up in court because they were caught by the morality department of the Toronto police. Long before the advent of video surveillance, police kept a close eye on what went on in the city’s toilets.

On May 11, 1922, just before midnight, Thomas P and James C were inside the lavatory at Allan Gardens. Thomas “was sitting on the toilet and his pants were unbuttoned and down and there was a hole cut through the partition between the compartments. He was looking through the hole then he put his hand through . . . to a man on the other side . . . James C was also sitting on the toilet at the same time with his pants unbuttoned and down. When Thomas put his hand through, James stood up, putting his rectum against the hole in the partition and Thomas then stood up and put his penis through the hole and started working towards James.”

Eventually, police officers came into the lavatory, catching Thomas and James in the act. The two men were arrested, found guilty of gross indecency and sent to jail. During the trial, one of the first questions concerned how it was that the police could see Thomas and James. The answer was to be found in the washroom’s architecture. As the court heard, there were two basic designs: the “open lavatory,” a space with urinals, and lavatories that also had compartments with doors.

As the two officers explained, “there is a hole in the wall at the back of the lavatory [and from the outside] you can look down into all the compartments . . . we have a platform built at the back so that we can.” The officers climbed up onto the platform using ladders. From this platform, “you could see both [compartments] at the same time.”

When caught by police, men improvised a number of ways to avoid arrest and its potentially devastating consequences. When Howard and Thomas were arrested, the police noted, “Howard F denied it [and] Thomas S said nothing.” Silence and denial were both common strategies; so, too, was giving a false name. Others expressed indignation. “It is absurd,” proclaimed one man to the charge that he had let another man suck him.

When Thomas P was first arrested, he said, “I am too excited to tell you anything.” But later Thomas came up with what he thought was a plausible explanation. He said that “he saw a hole in the partition and he got up just to see if his penis was big enough to go through the hole.” To explain why he required a helping hand from another man in the lavatory, Norman T said that “he had been under medical treatment and that he could not properly urinate.”

Many of these stories and strategies ultimately failed. But if we focus on that outcome, we will have missed the point. Even under the oppressive conditions of police surveillance and what must have been the frightening experience of arrest, men were not passive. Many talked back to the police. These were brave, early forms of resisting arrest. Remember, these men challenged the police in a period before the rise of an organized gay community.

Researching and writing about our pasts has important political uses. Following the bathhouse raids in 1981, for example, a group of historians working in the community-based Toronto History Group pored over old newspapers and compiled a long list of the bathhouses police had raided over the previous few decades. By doing so, historians were able to counter the police claim that the 1981 raids were an anomaly by demonstrating that, in fact, they were only the most recent and most brutal moments in a long history of police harassment.

History is also a humbling reminder that, clever as we post-Stonewall, post-bathhouse-raid generations are, we were not the first to boldly claim public sexual space in this city.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra