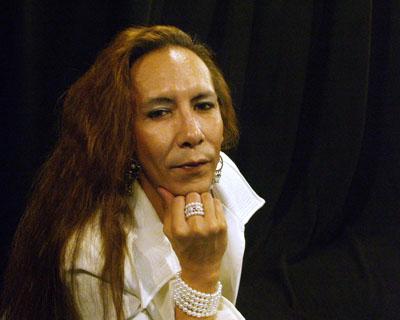

Gary Kinsman, co-author of The Canadian War on Queers and a professor at Laurentian University in Sudbury, compared G20 mass arrests with the 1981 "Operation Soap" bathhouse raids. Credit: David P Ball

Police across the country are seeking closer ties with gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender communities, but speakers at a recent international conference on policing questioned whether cops and queers make good bedfellows.

While noting that major police departments – most notably in Toronto – have developed queer community liaison programs, march in Pride parades and seem to take incidents of gaybashing more seriously, a number of prominent activists and researchers highlighted the costs of cooperating with law enforcement at the International Copwatching Conference, held in Winnipeg from July 22 to 24.

“LGBT and women’s movements getting into bed with the police has not made women and trans people of colour safer,” said keynote speaker Andrea Ritchie, from the group Incite: Women of Colour Against Violence. “In fact, working with the police has made us less safe.

“Policing is a system predicated on violence and sexual harassment. They’re constantly engaging in the policing of gender and sexuality – of classifying people as male/female, racial categories, class. Queer people are seen as disorderly and become objects of suspicion. Gender-nonconformist people are often stopped on the street, questioned or detained.”

Speakers recalled the police crackdown on the G20 protests in Toronto last summer, emphasizing that the shocking images of mass arrests and tear gas and reports of police misconduct are nothing new in Canada.

Gary Kinsman, a sociology professor at Laurentian University in Sudbury and co-author of The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation, spoke about organizing against the Toronto police raids on bathhouses in the 1980s. Those raids culminated in what was then the largest mass arrest in Canadian history. The mass-arrest record was unbroken until more than 1,000 were arrested during the G20 in Toronto last June.

During the G20 protests, queer protesters reported being segregated into special holding cages, facing verbal abuse from police and being threatened with rape. These allegations are currently under investigation, but the Toronto Police Service has so far not responded.

“We’ve seen an incredible mobilization of state power,” Kinsman said. “National security has always been targeted to expel some people from the fabric of the nation.”

Kinsman railed against claims that incidents of misconduct were the work of a few “rogue” police or mistakes of communication. The same excuses, he said, were made following the 1981 bathhouse raids.

“[The raids] were blamed on individual homophobia in the police, or a rogue unit of cops,” he said. “But if you base your activism on these sorts of perspectives, you don’t get at the root cause.

“We have to look at how the police are organized. After the G20, members of the queer community rallied against the police chief [Bill Blair] speaking at The 519 – but that’s not seen as part of what queer activism is about. It needs to be central. We need to work both within the law but also beyond the law.”

The conference explored police accountability from a variety of perspectives, bringing together organizers from across Canada and the United States. The event was hosted by Winnipeg Copwatch, a civilian police monitoring group that films police on patrol, educates people about their rights and protests against police brutality.

Racial profiling and racism against indigenous people featured prominently, as did discrimination against sex workers. In Canada, despite comprising only four percent of the population, indigenous people make up more than a quarter of the prison population. Those numbers are as high as 79 and 70 percent imprisoned in Saskatchewan and Manitoba respectively.

Alexus Young, a two-spirited Metis filmmaker from Winnipeg, spoke of being abandoned by police outside Saskatoon on a winter night in the 1990s as part of the notorious “starlight tours” — which came to prominence after the freezing death of Neil Stonechild in 1990. Young said police left her without shoes or jacket in sub-zero temperatures, and she was saved only when an elderly white couple stopped to offer her a ride.

“The police just decided I was a target,” the transgender artist said. “They just opened the door and said, ‘Get in.’

“I didn’t ask to be driven out of the city or sexually abused or beaten. I’ve lost three transgender sisters to violence. I never know if I will be attacked. But I won’t let that silence me. I now have a voice and I’m silent no more. As citizens we have to say, ‘That shouldn’t be happening.’”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra