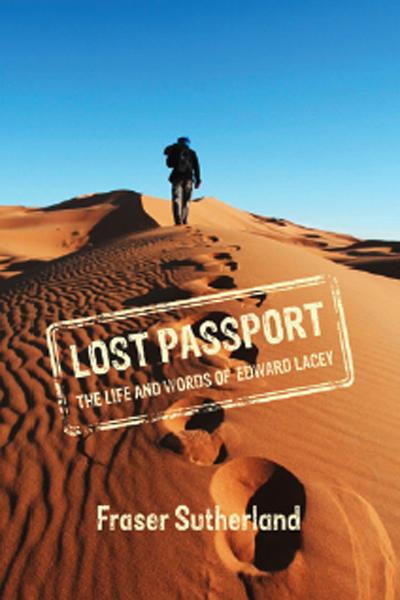

At the recent launch of his 16th book, Lost Passport: The Life and Words of Edward Lacey, author Fraser Sutherland began his remarks with an admission: “This is exactly the kind of event Edward Lacey would not attend.”

According to Sutherland, Lacey “always put life and living ahead of literature.” Lacey was, at times, a poet, teacher, academic, drunkard, vagabond and unrepentant explicator of gay sex. His wanderlust took him from a middle-class childhood in sleepy Lindsay, Ontario, to the US, Mexico, Trinidad, Brazil, Thailand and Indonesia. Since his 1995 death in a squalid Toronto rooming house, the man Sutherland describes as “a fascinating loner” has become one of the few in the exceptionally rarefied world of Canadian poetry to achieve an international reputation.

Sutherland is an accomplished poet himself, as well as a widely published journalist. He grew closest to the subject of Lost Passport after Lacey suffered the horrific accident in Bangkok that led to his repatriation to Canada. Even through the fog of the mental and physical damage of the accident, Sutherland claims Lacey maintained “a certain kind of charisma

. . . He was a kind of legendary wanderer, and some traces of that still lingered.”

I meet with Sutherland at his home in Toronto. As we chat – his friendly cat curled on my lap – Sutherland thoughtfully puffs on a pipe, the smoke hanging in the air before dissipating.

“I think Genet was a real intellectual influence on him,” he muses. “His whole conception of homosexuality . . . was a rebellion against bourgeois patterns.”

Like Genet’s, Lacey’s work is “a rebellion against the family, against social norms.” Sutherland believes that what tied Lacey’s love of travel to his appetite for promiscuous sex was the “recurring theme of a hunger, a yearning for intimacy.” For Lacey, sometimes, “it wouldn’t even be sex,” Sutherland explains. “He would meet a stranger and wanted nothing more than to be taken home [to] meet the family.”

However, Lacey’s outsider nature always led to loneliness eventually. Sutherland explains that “when he was offered intimacy . . . he would flee.”

As his smoke rings hang in the air, Sutherland speculates about the object of Lacey’s search. “He was looking for the great-good place . . . the great-good boy. But then it hardened into this attitude that there was no great-good place and there was no great-good boy.” Eventually, Sutherland says, “it became a kind of nihilism . . . Maybe,” he concludes, Lacey “was running away from the person he thought himself to be.”

Genet said, “The fame of heroes owes little to the extent of their conquests and all to the success of the tributes paid to them.” While there are no real heroes in Lost Passport, Sutherland pays worthy tribute to Lacey with meticulous attention to detail and a prose style that marries the journalistic to the poetic. In one scene, during an athletic sexual encounter, Lacey’s bed springs “creaked chaca chaca like a puritan protest.” Sutherland’s portrait of Lacey – at times the lugubrious drunk, the academic firebrand, the lover of language, the sexual consumer and always the nomad – may well contribute to exposing Lacey to a new generation of Canadians.

Ultimately, Edward Lacey’s quest for intimacy – and transgression against his bourgeois roots – delivered to the country he hated a body of work worthy of being shared with the world.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra