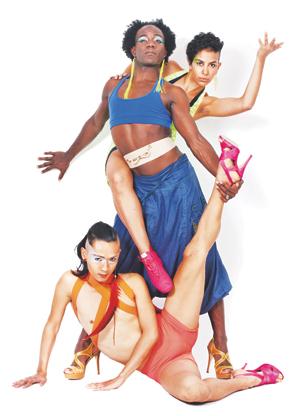

An Ill Nana performance can be like a ’90s R&B video gone drag: synchronized superhero posturing, aggressive femininity in masculine packages. It can also be tender and honest, telling stories of loss and friendship from a deeply personal place. It’s political, titillating and a middle finger to the exclusionary culture of mainstream dance. Naturally, the group will be doing numerous performances over the course of this year’s Pride festivities.

When Foxy Brown dropped her album Ill Na Na in the mid-’90s, it was a rare moment in the history of pop music. Fierce, sex-positive female MCs were all over the radio; Lil’ Kim, Missy Elliot, Da Brat and Left Eye were part of a movement that hasn’t been replicated since. The members of the Toronto dance company Ill Nana came of age during this era, and by taking the name of the Foxy Brown album, they unintentionally gave themselves a liberation manifesto.

“At the time we were exploring our feminine energy,” says Sze-Yang Ade-Lam, “because as a male dancer you’re not really allowed to do that. IIl Nana was the first time we wore heels and the first time that we had lipstick or wigs on. It was the first time we explored that at all. It was taboo for us.”

In recent years, Ill Nana’s founding members — now married — Sze Yang Ade-Lam and Jelani Ade-Lam, and new-blood Kumari Giles, have taken their lush hybrid dance performances from Toronto’s queer club scene to big mainstream stages while staying unapologetically themselves.

Between them, the three have spent decades rigorously pursuing professional dance careers. Ill Nana, which started in 2007 as a way to make dance fun again, has evolved into an equally rigorous rejection of that mainstream dance scene.

“I was still doing a lot of ballet,” Sze-Yang says of their genesis, “navigating the dance world and finding that we didn’t have a lot of opportunities even though we were highly trained dancers. I think that’s partly due to homophobia and to racism and just not fitting into the cookie-cutter image of what a dancer is supposed to be like and look like.”

From 2007 to 2009, Jelani, Sze-Yang and a rotating cast of friends performed in clubs and refined their vision. They were a dance crew in the hip-hop mould with an increasing sense of social responsibility. Then they landed a commission from the Art Gallery of Ontario to do a performance celebrating the work of Edward Steichen, the legendary high-fashion photographer. Things were getting serious.

On January 12, 2010, an earthquake hit Haiti. Like millions of people around the world, the sheer injustice of the devastation prompted the crew to act. They chose dance as their method of raising relief money.

“Until this point,” Jelani says, “we had left contemporary dance for a while and we were doing stuff with heels and hip hop and club dancing. It was amazing and really fulfilling for us, but for the relief fundraiser we decided to take off the heels, go back to contemporary and do something really heartfelt.”

The performance, sans props and makeup, resulted in an emotionally honest work that touched the audience and ended with the dancers in tears onstage. They’d reached a turning point. The loose collective of friends that danced as Ill Nana decided to stop wasting time trying to fit into a dance world that didn’t want them and do it for themselves.

“We figured out a structure,” Jelani says. “We figured out grants. We put together a mandate and a vision.” In 2010 they became Ill Nana the dance company.

“Before 2010 we were doing this for fun and still looking for the real job outside of Ill Nana. In 2010 it became ‘We can be the real job,’” Sze-Yang says.

Training to be a dancer as a queer person of colour can mean checking yourself at the studio door. For Giles — a queer South Asian woman — her years training in ballet and contemporary dance made her feel she was being erased: “My stories and my life while dancing in those spaces didn’t matter.”

Now, says Giles, “our lives come into the studio with us, and it is very much a political act to be in traditional dance spaces as ourselves, telling our stories and not leaving ourselves at the door when we walk onstage.”

Part of that inclusiveness means being open to many different styles. Along with ballet and contemporary, which they all share, the group has experimented with all kinds of movement, from Afro-Caribbean to Ukrainian to martial arts.

Though they don’t consider themselves part of the Toronto ballroom vogue scene, they are close friends with local vogue dancers and count the form as one of their great influences. For Ill Nana, voguing connects the dots between genres in a form that was created wholly within the queer community.

“When people are being homophobic and they call you a fag and a sissy and whatnot, it’s usually like gays are weak or gay people are effeminate or not strong. And to me, when I first saw voguing, I was like, Holy, they’re both effeminate and so powerful and so strong,” Sze Yang says.

“Because we’ve faced so much violence and negativity we needed to figure out how to be superheroes,” Jelani says. “We needed to figure out how to put out an image of what we wanted to be even if we weren’t that image: a superhero is the heels and the bright colours and being, ‘Hey, we’re here and we’re powerful and you can’t touch us.”

The two male members credit the recent addition of Giles to the company with tempering their club-land personas and moving them forward. Says Jelani, “The other side of being a superhero is Kumari’s humanness. It’s super powerful to be vulnerable onstage.”

Performing is only a small portion of what the company does: they run Right to Dance, a free drop-in class at The 519 for queer people who might feel uncomfortable in a conventional dance class; they offer a two-month intensive class that guides dancers through the process of creating group and solo pieces, ending in a performance of new work; and they’re working on getting annual funding to create a space “where LGBT people can put their own stories and experiences onstage.”

They’re also the winner of this year’s Spirit of Will Munro award, a $10,000 grant meant to establish a local arts project for queer youth. The company plans to use the money to organize a conference this fall consisting of classes, discussion and performances that will bring queer participants together with dance professionals in an affirming space.

This year’s Pride weekend will see Ill Nana performing at minimum four different events in what should be a range of styles, from hard-hitting hip hop to jazz and contemporary.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra