Remember the first time you noticed a national advertiser openly cater to gay audiences? If you’re like most of us, you probably felt a little pride in being acknowledged as a valued member of society. Depending on your age, it may also have been an emotional moment, as decades of invisibility and negative portrayal finally began to fade away. Your perception of that brand probably became much more positive, making you more likely to buy products sold under it.

But that’s only if you’re gay. If you belong to a group that’s antagonistic toward gay people – like some self-described Christian organizations – your reaction might be totally different. You might be outraged enough to accuse the corporation of legitimizing degenerate behaviour. You might even band together with some like-minded people to launch a boycott.

That is exactly how gay people react when we see a company that embraces anti-gay positions, like in the 1970s when brewer Coors fired all the gay employees its managers could identify. That resulted in a decades-long boycott of Coors’ beers by gay people.

Then there was the 1997 episode of Ellen in which the comedian was widely expected to come out as gay. Both Chrysler and JCPenney pulled their advertising after the American Family Association threatened to boycott the show’s sponsors.

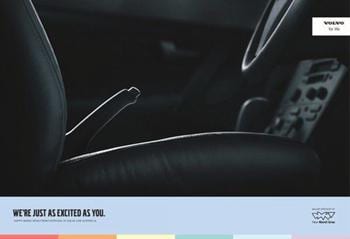

In 2003, Volvo, then a Ford subsidiary, ran an ad for the Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras in Sydney, Australia. The visual was playfully phallic, but US Christian groups were not amused. They found the ads offensive and in 2005 called for a boycott of Ford. Within months the company announced its subsidiaries would no longer advertise in gay publications.

Now, back to Ellen and JCPenney. When the retailer finally came to its senses this year and named Ellen its spokesperson, a group called One Million Moms urged the company to drop her or face a boycott. But this time JCPenney stuck with Ellen and a counter-boycott was organized to encourage people to shop at the store.

Why do major advertisers take sides at all when it so often leads to protests and boycotts? It rarely has anything to do with morality. Corporations aren’t people; they don’t have feelings. These are business decisions crafted to win customers, attract employees, earn higher revenues or all three.

Advertisers don’t embrace the gay community because it’s the right thing to do. They do it because we’re increasingly visible, have above-average disposable income and tend to be on the leading edge of new trends. Advertisers don’t embrace the Christian right because God tells them to. They do so to appeal to a large base of aging, non-urban customers who respond well to such points of view.

Ultimately, it’s a numbers game. Company managers choose whether the customers it gains are worth more than the customers it stands to lose. In the case of JCPenney in 1997, that calculation led to dumping Ellen. In 2012, the same calculation made her the public face of the company.

But let’s be clear. It’s not that JCPenney, eBay or Microsoft love us; they are starting to treat us like they’ve always treated everyone else simply because they want our money.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra