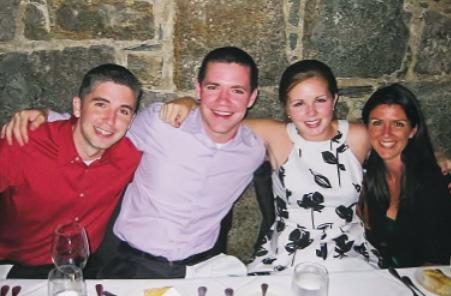

A FAMILY TORN APART: The Burke siblings, Patrick, Brendan, Molly and Katie. Brendan was killed in a car accident in 2010. Credit: Courtesy of Patrick Burke

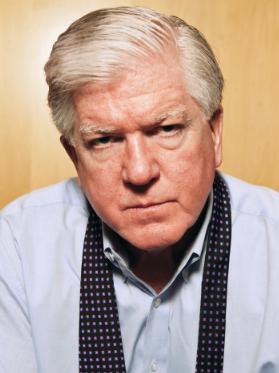

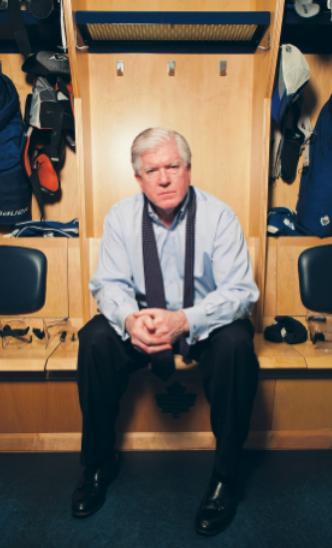

The president and general manager of one of the most popular teams in the National Hockey League is an unlikely activist. Credit: Steve Payne

Before his youngest son came out in December 2007, Toronto Maple Leafs president and general manager Brian Burke didn’t know a single gay person. That was about to change.

The following summer, Brian and Brendan attended the Toronto Pride parade together. The famous father and son were just two faces among thousands of revellers in the crowd: cheering, laughing and watching the rainbow-decorated floats pass by. Like other dads, Burke worried he would embarrass his son. “I asked him, ‘Who is more embarrassed here? The GM of the Leafs or a kid at the Pride parade with his dad?’” he recalls. “He said, ‘Dad, are you kidding? I’m more embarrassed.’”

The experience left an indelible impression on Burke and helped cement a bond with his son that would shape the next four years of his life.

Publicly, Brendan was still living with a secret. With the support of his family, he made the decision in 2009 to come out to the world. While the act of coming out, especially under such unwelcoming pressures, was itself an act of rebellion, he went even further, proudly and naturally stepping into the role of advocate for gays in sport.

Burke was behind his son every step of the way, appearing on ESPN and challenging anyone who dared contest Brendan’s declaration.

Then, in 2010, the unthinkable happened. Just two years after Brendan came out privately to his family, Burke lived through every parent’s worst nightmare. Brendan, just 21, was killed in a car accident in Indiana.

Burke’s journey since then is the tale of a man who now desperately wants to make his gay son proud. Brendan did not die in vain and Burke is making sure of that. Brendan, a former goalie for the Miami (Ohio) University hockey team, is now widely credited as the highest-profile player connected to the NHL ever to kick the locker-room door wide open, forcing professional hockey to address its deeply ingrained homophobic culture.

To honour Brendan’s memory, Burke and his eldest son, Patrick, a scout for the Philadelphia Flyers, now carry on that legacy.

Patrick recently founded the You Can Play project and produced a moving video featuring NHL stars. The message is a simple one: it doesn’t matter who you fall in love with. When a player steps onto the ice, it matters only how they skate, how they shoot, how they score. If you can play, you can play. Period.

Burke and Patrick say it’s only a matter of time before the first gay NHL player comes out.

“I think the first athlete that comes out will have a much easier time than he thinks,” Burke says. “The young generation gets it. It’s my generation that has to change their thinking.”

Over the last two months, I had met Brian at two public appearances: a Toronto PFLAG awards ceremony and a Canadian Safe School Network luncheon. He calls me “kiddo” and is always happy to speak with Xtra. But trying to get Brian Burke one-on-one was challenging. He is a busy man.

However, true to his word, after eventually agreeing to an interview, Burke came through, and I had the chance to sit down with him at his Air Canada Centre office. The week I met him, Burke and his son Patrick were all over the media launching You Can Play. Burke was also in the news for other reasons.

The day of our interview, Don Cherry was calling for Burke’s resignation in the Toronto Sun. The two were engaging in a very public war of words about former Toronto Maple Leafs coach Ron Wilson and whether there are too few Ontario players on the team. Another interview with Newstalk 1010’s John Moore ended abruptly when the tough-talking GM hung up the phone following an unexpected question: Moore asked about speculation that Burke might be fired after failing to get the Leafs into the playoffs.

But unlike Moore, I wasn’t going to ask Burke many questions about the playoffs. Our interview ended differently when, standing in the locker room, the sour smell of sweaty hockey socks lingering in the air, Burke leaned in and gave me a big hug. Beneath his rough exterior, I felt a softness, something he rarely shows publicly — and never at a hockey rink.

Burke is gruff — he calls himself a “big Harley-riding, sports-playing, tobacco-chewing tough guy.” But underneath is a warm intensity. The graduate of Harvard Law School is humble and chooses his words carefully, pausing when tears well in his eyes. He softens when he speaks about his children, especially Brendan, who Burke nicknamed “Moose.”

“Brendan was a big kid, six foot four, and a good athlete. Patrick has an edge to him, more like his dad,” Burke says. “But Brendan was a sweet kid. Not a judgmental bone in his body. No temper.”

Burke is an unlikely activist, but it’s a title he now wears with pride. PFLAG Toronto’s Irene Miller remembers the day Burke asked her for an application form.

Miller, who did not know Brendan personally but had followed his story, says Burke’s message is incredibly powerful, mostly because he doesn’t really consider his work activism; it’s just what every parent should do. “Brendan was someone special, and that’s a testament to Brian,” she says. “He is a loud and wonderful voice that is spreading such a positive message. The sports world is one of the last bastions of society where it’s okay to be homophobic. Brian is saying, No, it is not. It’s not accepted.”

Influenced by Burke and his sons, an “all-star team” of straight-ally players is also advocating this message. The You Can Play campaign includes players such as the Columbus Blue Jackets’ Rick Nash and the Maple Leafs’ Dion Phaneuf. Homophobic locker-room bullies, beware.

Burke applauds the players and hopes more follow suit. “This is not a popular cause. You can get anyone to march for breast cancer. You can get anyone to march to save baby seals or to fund the United Way. There are all kinds of popular, sexy charities. The gay community hasn’t had that kind of support. I think this is important and that’s why I support it.”

While most have heard the story of Brendan’s death, not many know how deeply it affected the Burke family. The father-son relationship, which was on the threshold of a newer, stronger bond, was suddenly ripped apart.

As he recalls those difficult days, Burke hunches with his elbows resting on his knees, his tie casually draped around his neck, as if he’s too busy to bother tying it up.

He struggles when it comes to discussing his son. “I can’t talk publicly about Brendan too much yet, but I’ll do the best I can,” he says, looking down. The pain is still fresh, and probably always will be.

When he speaks about Brendan a wistful sadness washes over his face that forces him to look down at his feet. Burke describes Brendan as gentle, outgoing, cheerful and patient — “nothing like me.” Magnetic and handsome, talented and smart, Brendan was a great hockey player who Burke says probably would have gone into politics. “He wanted to make the world a better place.”

That’s a mission Burke now carries on. He is beloved by his team and has their support in his advocacy work, but, in speaking to players, the enormous mountain Burke has set out to climb becomes clear. The willingness to accept a gay player is overshadowed by a hesitation to discuss sexuality, a topic still very much off-limits in the locker room.

“As far as athletes are concerned, everyone has their own thing, their own belief. Some choose to keep it personal,” says Leafs’ alternate captain Mike Komisarek.

While Komisarek’s heart may be in the right place, his conviction that being gay is a belief illustrates the difficulty of Burke’s task and the battle his son would have faced if he’d lived. But that’s a battle Burke is prepared to fight.

Leafs’ defenceman John-Michael Liles admits that the first gay NHLer will face enormous challenges, both on and off the ice. “I think it could be tough. You never know. There are a lot of people in sports that have opinions and some aren’t very welcoming, and that’s not just players.”

When Brendan was young, Burke says, he was taught to respect all people. “There was no racial humour tolerated, no homophobic jokes. There were no religious judgments that some kids had to deal with — parents telling them they are going straight to hell. So there was no big adjustment for me. When he came out, I said to Brendan that night that it changes nothing. So I was especially proud I didn’t have to take anything back.”

Two years after coming out to his dad, Brendan, who was a manager of the Miami University hockey team, revealed his sexuality to his team. Coach Enrico Blasi supported him, telling ESPN at the time that having Brendan as part of the team was a blessing.

Burke doesn’t conceal his anger when he remembers the advice he felt he had to give Brendan when he came out. “It took a lot of courage,” Burke says. “I told him, ‘For the next couple months, you have to be careful; keep your head on a swivel . . . I don’t want any Matthew Shepard story here.’ That’s the sickest part of this entire story — I had to give him that advice. That’s the advice a father has to give a gay son. That’s pathetic.”

Burke just wanted to keep his son safe. “The pioneer is usually a lonely guy,” he says.

While Brendan received immediate acceptance from his father, that’s not the case in all families. “I get these gut-wrenching letters from parents asking me how to deal with their kid’s sexuality. I also get heart-wrenching letters from kids. It’s very upsetting,” he says.

He recalls one letter from a fellow hockey dad. In it, the father described driving with his son, who suddenly asked his dad to pull the car over. The son took a deep breath and came out. “The father turned to his son and said, ‘If it’s good enough for Brian Burke, it’s good enough for me.’”

Patrick hears them, too: tough stories of kids kicked off sports teams, kicked out of homes. Some contemplate suicide. It’s rapidly improving, but not fast enough. Even one story is too many. “We are losing young athletes; some because we scare them off with homophobic slurs, some because they never get into sports in the first place,” he says.

Patrick says the You Can Play project is actually fighting both a reality and a stereotype. The reality is that homophobia has become deeply embedded in the hockey culture. It’s how players bond. Many don’t even realize what they’re saying is offensive: “fag,” “homo,” “sissy.”

The stereotype is that players don’t care. “Many people think athletes are these big meatheads who walk around beating people up, never thinking twice. So we are battling that as well. Over the years, straight athletes have been conditioned to think they should not support gay rights. We need to give them a means to support gay players. The vast majority of them do,” Patrick says.

The education starts at home with the hockey parents, he says. The cycle can end in the home. How parents raise their sons will be where the culture of homophobia will finally be broken.

Burke maintains he would have become involved in the cause even if Brendan hadn’t died.

In 2011, the year after Brendan’s accident, Burke was back at the Toronto Pride parade, this time marching with PFLAG. He even tried unsuccessfully to convince Mayor Rob Ford to join him. At his side were Rick Mercer and numerous fellow parents and family members. It was a moving experience, he says.

In January, Burke was honoured with the Ally Award from PFLAG Toronto. A man of few words, he choked back tears on stage and muttered, “I’m honoured,” softly into the microphone, before stepping away.

PFLAG’s Miller applauds Burke because he is helping young gay athletes feel validated. She hopes that a young athlete in some small Canadian town, who sees Burke standing up to homophobic bullies, may decide to follow his dream into sports. He may come out sooner. He may decide not to commit suicide. “For Brian Burke to be on the cover of Xtra is huge,” Miller says. “That 15- or 16-year-old kid who is questioning and wondering who his role models are, seeing Brian on Xtra tells him he will be okay.

“It will also shake up the rest of the sports world. It says he doesn’t give a damn what people think. He only gives a damn about changing pro sports.”

Since the release of the You Can Play video, more and more NHL stars are adding their voices to a growing chorus of players pushing to end homophobia in hockey. Patrick predicts the NHL will see its first openly gay athlete in the next two years. “We have hit the tipping point here. We are getting closer and closer to that moment.”

When the day comes and a player enters his office to come out, Burke knows just what he will say.

“I never had a chance to rehearse this the first time for my son, but I’ll get it right the second time,” he says. “I’ll just say, ‘Welcome aboard.’”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra