A scene from Where the Wild Things Are.

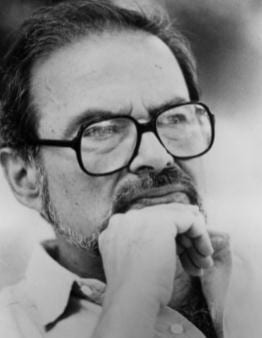

Gay American writer and illustrator Maurice Sendak died from complications following a stroke on the morning of May 8 in Danbury, Connecticut. He was 83.

Sendak came out publicly at age 80 in a 2008 New York Times interview, revealing a secret his parents never knew. “I just didn’t think it was anybody’s business . . . All I wanted was to be straight so my parents could be happy. They never, never, never knew,” he said.

Sendak lived with his partner, psychoanalyst Eugene Glynn, for 50 years. Glynn died in 2007 from lung cancer.

The prolific artist illustrated more than 100 books and wrote 20. Best known for Where the Wild Things Are, which had sold more than 19 million copies as of 2009, he also created opera and ballet sets and TV shows. He worked on the Canadian TV co-production Little Bear and with the National Film Board on a short film.

Collaborators throughout his career include Tony Kushner, Jim Henson and Spike Jonze. For his body of work he earned the National Medal for the Arts, the highest arts honour in the United States.

Born in Brooklyn on June 10, 1928, to immigrant Jewish parents, Sendak spent much of his childhood in bed with health problems. It was there that he developed his love of storytelling and illustration, in part from hearing stories of his father’s Polish homeland that bridged fact and imagination.

These moments made him focus on mortality. As his extended family was dying in the Holocaust in Europe, his father’s mythical tales became foreboding and haunting to the bedridden son. Even the Lindbergh baby kidnapping was an obsessive source of anxiety — if that could happen to a child of privilege, what about him?

He expressed his youthful sense of delight, mystery and sadness through his art, as reflected in influences as varied as Disney’s Fantasia and Pinocchio, Emily Dickinson and William Blake.

These interests allowed Sendak to escape his limited Brooklyn experience. He told journalist and author Jonathan Cott that he was “miserable as a kid . . . I couldn’t make friends, I couldn’t play stoopball terrific, I couldn’t skate. I stayed home and drew pictures. You know what they all thought of me: sissy Maurice Sendak.”

With the support of his elder brother Jack — they collaborated on stories growing up — Sendak got through this period. But coming out in pre-Stonewall New York was not in the cards, particularly for a children’s author.

Sendak got his start doing technical illustrations for textbooks and window displays for New York toy store FAO Schwarz. At the fabled store he spoke with the book ordering manager and was put in touch with an editor at Harper Row. It became his publisher for the next 60 years.

As his career took off, Sendak maintained his generous spirit toward children. He made a policy of answering every letter received from his young fans, often with ornate drawings on the envelope. Kids devoured his work, sometimes literally. In an interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, Sendak described one of the best compliments he received, when a child got a postcard from the author with a drawing of a Wild Thing and ate it. “That to me was one of the highest compliments I’ve ever received. He didn’t care that it was an original drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it.”

University of Florida professor Kenneth Kidd, a specialist in children’s literature, argues that the unique and queer imagination of Sendak fostered the same sensibility in a mass audience. “Where the Wild Things Are has a curious status, belonging to everyone and celebrated as a universal story, but with an intensely personal origin . . . (Max) is queer to some degree – hard to manage, independent, animal-identified.”

This universal sense of individuality inspired other artists and creators. On Twitter, author Neil Gaiman wrote, “He was unique, grumpy, brilliant, gay, wise, magical and made the world better by creating art in it.” Children’s author Judy Blume added, “I cannot put into words what I am feeling, what he and his work meant to me.”

Sendak leaves behind no immediate family, one dog and millions of readers ready to continue his wild rumpus.

Maurice Sendak tribute

Fri, May 18, 7:30pm

Glad Day Bookshop

598A Yonge St

gladdaybookshop.com

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra