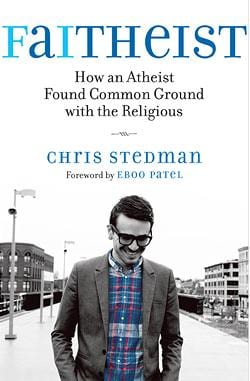

Credit: Alex Dakoulas

What do you think of when you hear the description “gay, atheist 20-something”? Images of a future seminary student talking intently with Christian street preachers outside the neighbourhood gay bar probably aren’t the first that come to mind.

But Chris Stedman is not your average gay, atheist 20-something. The author of Faitheist has already earned two university degrees, created the popular blog NonProphet Status, and become assistant humanist chaplain at Harvard — all before most of his peers have finished filling out their job applications at The Keg.

In other words, Stedman is the kind of high-profile, pro-religion atheist who has a couple stories up his sleeve. So people started asking him when he was going to write a book. “I said, ‘Oh, you know, if I do it, it’ll be in five or 10 years.’” But a friend wasn’t buying the time line. He told Stedman to just start writing and see what happened. “And before I knew it, I had a lot of the book done.”

Faitheist is partly a call for interfaith cooperation. But it’s also, for the most part, a memoir.

Stedman starts with his nonreligious childhood. After becoming a closeted evangelical Christian, he is nearly driven to suicide by his own homophobic thoughts. His mother finds a gay-positive pastor, however, who helps bring him from the brink of his own self-hatred. Stedman starts doing queer activism in the church before eventually becoming an atheist. The atheist community he finds, however, is hardly the space of tolerance and pluralism he was yearning for.

Today, Stedman travels widely for speaking engagements about secular social-justice activism and religious diversity. “Often I’ll also lead a workshop . . . and the first thing I’ll do is I’ll ask the people in the room to share what words, ideas, phrases, images come to mind when they hear the word ‘atheist.’”

“Mean-spirited,” “arrogant,” “anti-religious”: the words that usually get thrown back to him don’t bode well for secularism’s reputation. Stedman credits part of the anti-atheist sentiment to messages from the media, including vocal atheist bloggers and pundits. But perhaps more importantly, he points to “negative interpersonal experiences with atheists.”

“One way to combat a lot of these negative ideas out there,” he says, “is in interfaith contexts.”

Stedman’s not naive. His family was asked to find a new church when he was a kid because of his activism. He’s been attacked in a Chicago train station while sitting with a friend waiting for the next ride home. But he holds on to an unflinching — even religious — faith in the possibility that people can change.

We’re about to wrap up our interview and Stedman stops. He wants to tell me a story that’s not in his book. “It was on Valentine’s Day,” he remembers: Feb 14, 2011.

He was speaking at the University of Illinois about inter-religious cooperation. At the end of his presentation, a woman walked up to him. She stood in front of him, shaking, “and told me that I had a demon inside of me that was making me gay.”

The words were a trigger. He remembered the junior-high lunch hours he spent fasting in repentance of his character. He remembered the afternoons after school, when he went home to be alone, writing in his journal and marking his Bible obsessively with highlighters. He remembered being 13 years old, holding himself back in the shower from taking his own life.

Stedman had no idea how he was going to react. Looking back, he says, he would have been well within his rights to ignore her or even break down and cry. He might have mocked her or dismissed her entirely, he says: “Interfaith dialogue is contingent on a two-way street. There has to be a mutual respect there . . . and she clearly wasn’t showing me that.”

But instead, he paused and spoke back softly.

“Thank you for being honest with me,” he said to her. “I know it can be really hard to tell someone something that they really need to hear but maybe they don’t want to, and that’s brave of you to do.”

Originally expecting a confrontation, the woman was taken aback, Stedman remembers. Instead, the pair began to talk about their beliefs and their values. He walked her through what it felt like to be a young kid who believed that he did have that demon inside of him. He told her about how he accepted himself for the person he is.

As a storyteller, Stedman says, he’d love to be able to tell me that she walked away changed. “I can’t say that.”

“But I can say that because she had the opportunity to hear me out and get to know me a little bit, now she has another point of reference,” he tells me. “When she hears a minister preaching about it, when she sees the news and there’s a ballot initiative up for a vote — now, when she hears the word ‘gay’ or ‘LGBT’ or what have you, she has to connect it with a person.”

Is he hopeful about her, I ask? “I am. I am, yeah. And I would rather try to respond to acts of hate or ignorance with love . . . and inject some humanity into that moment.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra