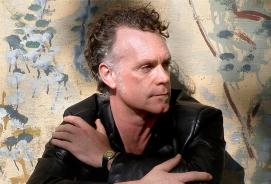

Toward Light includes Odetta's Songs and Dances (1964), choreographed by Rachel Browne and performed by WCD dancers. Credit: Leif Norman

The world of dance has frequently offered queers a safe space to come out. But in the case of Brent Lott, it was seeking a space to come out that accidently brought him to the world of dance. Lott, who is the artistic director of Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dancers, says his first inkling that he might be suited to the art form came while he was trying to cruise guys on the lawn of the Manitoba legislature.

Lott had been sent to the well-known pickup place by his then-wife. Having recently departed the Evangelical Christian church, the couple had come to understand their marriage was no match for his same-sex desires, and she’d pushed him to visit the popular sun-tanning spot in the hope he’d meet a nice guy. Everything changed when a handsome hunk decided to flirt by commenting on his arches.

“He walked up and said I had beautiful feet for a dancer and my heart stopped,” Lott says. “I’d wanted to be a dancer as a child, but my father thought it was too gay. The guy was at the ballet school and he pushed me to try out. Two days later I was doing an audition in clothes I’d borrowed from him.”

The chance meeting catalyzed a career spanning two decades. After two years at the ballet school, he moved to Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dance School, founded by Canadian dance icon Rachel Browne – who also launched the company he now heads. WCD’s current turn is Toward Light, an expansive tribute to its founder, who passed away last June. Ranging from Browne’s earliest work (an excerpt of 1964’s Odetta’s Songs and Dances) to the last piece she made before her death (2012’s Momentum), the evening paints a picture of an artist unafraid to push her dancers to their absolute limit.

“I remember being terrified of her the first time I took class with her,” Lott says. “It’s funny because she was this tiny woman with a huge head of grey hair. She set the bar so high you didn’t want to disappoint her. But I quickly learned even though she was incredibly demanding she had the biggest of hearts.”

While Browne never formally came out, hints of queer identity percolate through some of her pieces included in the program. My Romance (1990), a solo about a failed relationship for one woman, was rumoured to have been made for a female love interest. Freddy (1991) follows a woman as she dons male drag and descends into a Berlin lesbian bar for the first time.

Despite lacking overt queer content, Browne’s work had a distinct feminist sensibility from her earliest days, when it was radical for women to dance with bare feet and free-flowing hair instead of pointe shoes and slick buns. Starting a company in 1964 also represented a radical shift in what was still a male-dominated industry.

“There were no other women running dance companies in Canada,” Lott says. “There was no one for her to look up. She had no mentors. She was doing it entirely on her own.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra