In one of the essays in their new collection, Mega Milk, Megan Milks imagines inhabiting the character of Mickey, the protagonist of Maurice Sendak’s classic children’s book In the Night Kitchen. In that book’s most memorable scene (I can still picture it now, decades after reading it), Mickey flies around in an airplane made of dough and then dives naked into a gigantic bottle of milk and swims around. The scene is both zany and strangely sensual—which isn’t a bad description of Milks’s writing. The essay probes Sendak’s book from various angles, touching on Sendak’s queer coming out late in life; the book’s censorship over the decades and what Mickey’s dive into dairy might mean. “Is Mickey returning to infancy,” wonders Milks, or is he expressing autonomy by finding and enjoying milk that is not from his mother?

Mega Milk’s essays focus, with surgical intensity, on different aspects of milk, in conversation with autobiographical inquiries into Milks’s own family, working life, sex life and relationships. One of the main tensions in Mega Milk is Milks’s desire to be an active part of their family of origin (they grew up in white, middle-class, semi-rural Virginia), while also needing to make family elsewhere, because of the important parts of themself (queerness, transness, leftism) that some members of their family don’t tolerate. They dive into this difficult material with honesty, some resentment and a refreshing curiosity. This curiosity endeared me to the book and kept me engaged, even when I grew tired of the overwhelming amount of dairy facts in some of the essays. “I’ve fallen in,” Milks writes, to describe the way in which they tend to plunge into a specific topic obsessively and exhaustively. Like Mickey, they don’t hesitate to swim around in the milk, and their friendly, matter-of-fact approach to their material beckons us to join them.

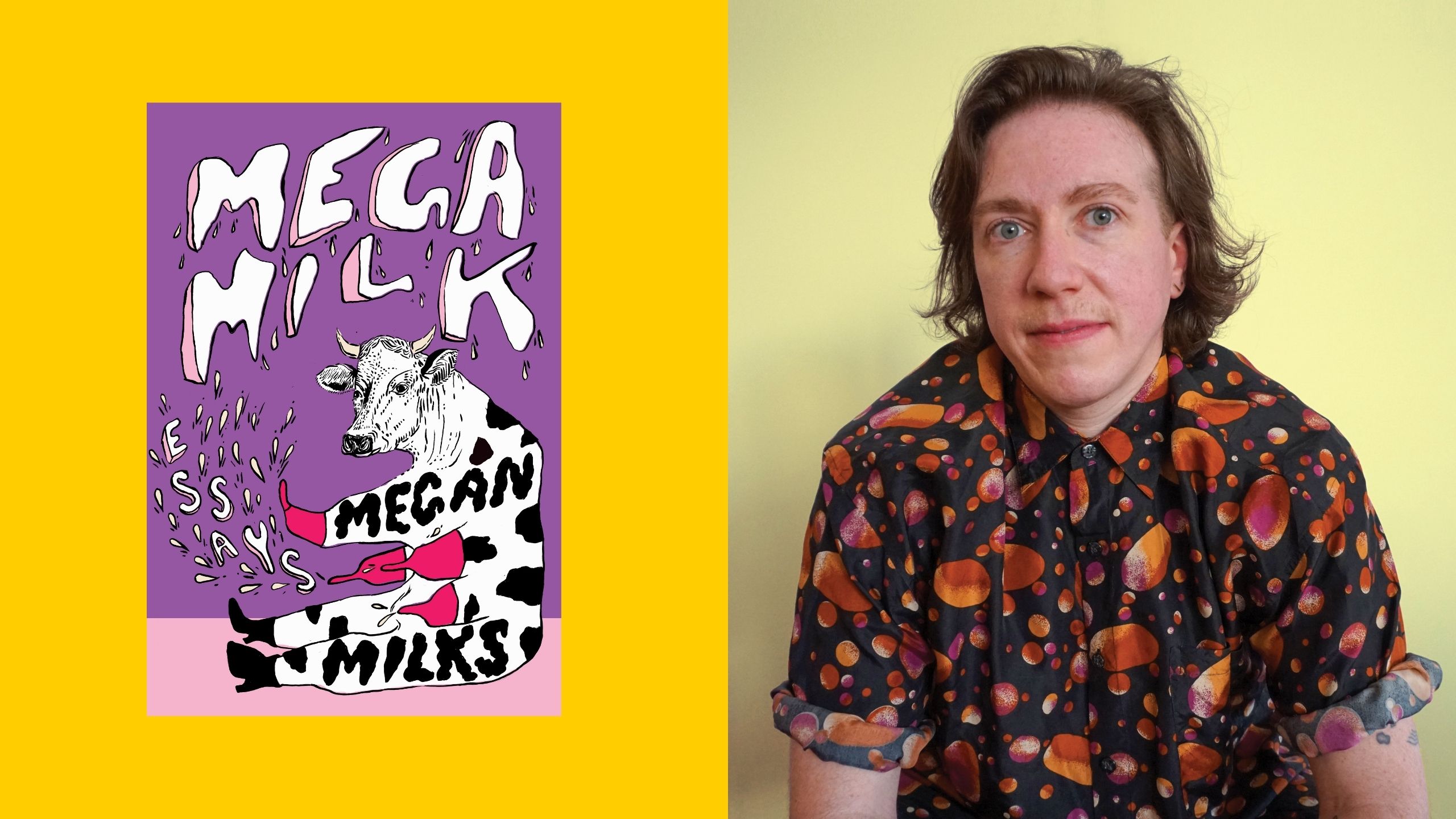

Mega Milk is Milks’s third book and first collection of essays. They are also the author of the novel Margaret and the Mystery of the Missing Body, and the short story collection Slug and Other Stories. Given that Milks is known for their weird fiction, dedication to writing queer and trans sex and interest in the surreal and the gross, milk might seem like an unlikely topic of interest for them—overly safe, perhaps boring. Milk is a substance so ubiquitous, at least in North America, that it feels difficult to be curious about it. It’s everywhere, it’s in everything, it has been marketed to us ad nauseam—what more could there be to say about it?

Milks themself has an ambivalent relationship with milk: They have always been associated with it because of their last name. They have also often been associated with cows, due to their unfortunate, possibly fatphobic, nickname as a child, “Megan Milks the Cow.” But they aren’t against milk or the drinking of it, they clarify. And as it turns out, they have found plenty to say about milk, both what it is and what it symbolizes. Mega Milk interrogates milk through a vast array of subtopics: changing cultural narratives about breastfeeding; the milking of cows; the artificial insemination of cows; the history of baby formula; the realities and constraints of dairy farming; milk and its associations with “wholesome” whiteness; milking as a euphemism for sex and masturbation; milking as a compelling theme for sexual roleplay; and the association of milk with parenting, family and genealogy.

“I have often used fiction as a space for processing (trauma and everything else),” Milks told BOMB in 2022. “I see it as a tool for invention, fantasy, revision, flattening, compartmentalizing, cross-identification and general interrogation of the self and experience.” Now that they have moved into non-fiction with this collection, these preoccupations are perhaps even more overt. The essays in Mega Milk have them processing difficult moments and relationships, often with their family, almost in real-time. In “MAGA Milk,” they reach out to their estranged brother, a Trump supporter, to try to interview him for the book, and include the thwarted attempt at communication, as well as their own feeling of guilt about the estrangement, in the text. In one of the standout essays, “Skim Milk,” they reflect on the need to bring a “skim milk” version of themself to family gatherings, which means downplaying their queerness and transness, so as not to create conflict. They contrast this with a friendly and open exchange with their parents about their portrayal in the book, after accidentally sending an unedited version of the essay to them. Throughout the book, they ask us to consider: What do we owe to those who raised us, fed us, who gave us milk?

Of course, not everyone is fed by the milk of their parents—many babies have been and continue to be raised on formula, cow milk. Milks chooses to lean into their old, resented nickname: they set out to learn about milking, in order to get to know dairy cows. In a recurring series that punctuates the collection, “Dear Dairy,” they visit a host of dairy farms and meticulously record what they notice and learn. They listen to farmers’ justifications for the automation of milking, exploitative migrant labour and the limited grazing time of cattle on industrial farms. During an informal internship on a small, organic dairy farm in New York, which prioritizes animal care, they get intimate with the cows, learning to milk them by hand, learning to hug them the right way in order to calm them down. “Cow time is different, slow,” they write. “Consumption and digestion are an ongoing process.”

Reading Mega Milk is an exercise in slow, curious contemplation. It is both hyper-focused on milk as a recurring subject, and surprisingly diffuse, moving in various directions, each essay a grab bag of milky ideas. These ideas usually come together in satisfying ways, though some essays feel a little loose, as in “MAGA Milk,” in which Milks tries to tie the history of white supremacy and milk to their own brother’s right-wing politics. There is something missing in this essay, I felt while reading, a hole in the middle—because the estranged brother is not willing to talk to Milks, not about his politics, nor about his relationship with them; he barely exists in the essay, and his white supremacist beliefs mainly have to be guessed at, or recalled from decades prior. Elsewhere, as in the final essay, “Squeeze,” Milks is able to form connections between seemingly disconnected topics: the manual squeezing required to milk a cow; the cow-squeezing machine that calms cattle on their way to slaughter; and their own sense of being a cow in capitalism, squeezed dry, their many literary and teaching jobs barely making ends meet: “I’m producing as much milk as my body can make.” At the essay’s conclusion, they squeeze the essay itself, rewriting it as a hyper-compressed block of prose, and then as an even more compressed poem.

After their brief stint helping out on the organic dairy farm, Milks drinks a glass of milk from the cows there, even though they aren’t normally a milk drinker. “I honor the cow,” they write. “I drink the cow and I taste the animal, the barn in my mouth.” Mega Milk is a book that honours the cow, which is sometimes an actual cow, sometimes a steer, but is also family, queer relationships, food systems, kinky roleplay and all the other topics that Milks pours into their text. This honouring means close attention, means approaching topics and people (and liquids) with an open spirit, the senses alert to new information. Mega Milk is excessive and leaky and exuberant and a little nasty. Readers, lap it up.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra