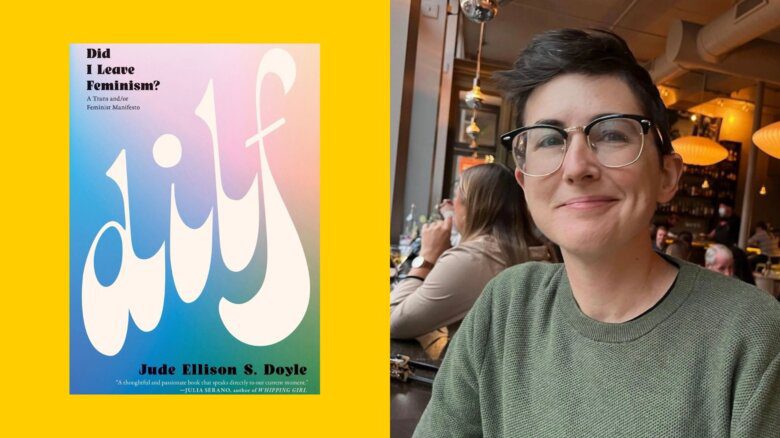

The publication of Gendertrash From Hell is a major event. The book, edited by Mirha-Soleil Ross, collects the four published issues of the original iconoclastic trans zine of the same name, first printed and distributed from 1993 to 1995, as well as the materials for a fifth issue that never got finished, and an archive of additional materials from the vaults. This is the first time that the zine and its ephemera have been published in book form. Gendertrash, from its inception, was created in order to give “a voice to gender queers, who’ve been discouraged from speaking out and communicating with each other.” Its five issues, edited by Toronto-based then-girlfriends Mirha-Soleil Ross (aka Jeanne B.) and Xanthra Phillippa MacKay, provide a searing, witty, critical and defiant view of trans lives, struggles, desires and philosophies. It feels just as pressing now as it did in the early 1990s. That LittlePuss Press, the publisher of this volume, is run by two trans women provides an additional thread of connection between past and present.

Mirha-Soleil Ross is a legendary trans activist, video artist, sex worker and performer. In 1998, she founded the first-ever trans film festival, Counting Past Two, with support from MacKay; she has also created multiple one-woman performances including Yapping Out Loud: Confessions of an Unrepentant Whore. Her activism has focused on trans rights, sex worker advocacy and animal rights. MacKay was a video artist, activist and radio show host. In addition to collaborating on Gendertrash, Ross and MacKay also made art together: their short film Gendertroublemakers (1993) featured two trans dykes, “an uncompromising in-your-face flick about their shitty relationships with gay men and their unabashed attraction to other transsexual women.” The pages of Gendertrash are filled with poems, essays, rants, fictions, speeches, surveys, interviews, resource lists and personal ads—largely for and by trans people, against the straight establishment, as well as the cis gay and lesbian movement, who were only too happy to throw trans people under the bus in order to gain rights for themselves. Sound familiar?

The editors, as well as many contributors to the zine, voiced their dislike of the term “trans” at the time, because of its origins in medical terminology; they preferred “gender described” or “gender queer,” although some pieces use the terms “transgendered” and “transsexual” as well. I use “trans” in place of “gender described” in this review, since it’s the more current terminology.

In her afterword, Leah Tigers, well-known essayist and self-described “trans woman on the internet,” notes that although Gendertrash was not the only trans zine circulating at the time, it was distinguished for its staunchly anti-capitalist, pro-sex worker, anti-prison stance. “You already know if this is a book you agree with,” she writes, referencing its brazen title. She places Gendertrash in context: its four issues were published during the third-wave feminist resurgence of the early 1990s, alongside other queer and trans zines like Homocore, J.D.s and Diseased Pariah News, as well as TransSisters: The Journal of Transsexual Feminism and In Your Face!, both of which were publications run by trans women who also collaborated with Gendertrash by writing articles or trading ad space. Gendertrash stood out for being a Canadian publication, with contributors from across the country, while TransSisters and In Your Face! were American. Tigers highlights the fact that Gendertrash is unequivocally pro-sex worker, which other similar publications from the U.S. were not. Ross herself wrote many pieces for the zine under a pen name, Jeanne B., from her own perspective as a sex worker, and conducted in-depth interviews with other current and former trans sex workers.

Gendertrash was particularly sought after by trans prisoners in Canada and the U.S. for its practical resources as well as its emotional and political solidarity. Eventually, several contributions from incarcerated trans people were featured in the zine. Its contributors took issue with academia’s obsession with studying trans people rather than listening to their actual survival needs; with a medical system that didn’t recognize trans people as being at risk for HIV/AIDS; and with liberal gay and lesbian organizations that routinely erased, co-opted or shamed trans people and their struggles and achievements. Despite all this, Tigers reflects that Gendertrash didn’t have a wide impact, outside of “equally local, marginal countercultures.” However, its editors continued to make an impact in the world of trans activism after the zine’s run ended.

Ross cofounded Meal Trans, a drop-in program for poor, homeless and sex-working trans people at The 519 in Toronto, which still runs today; Xanthra Phillippa MacKay hosted a radio show for and by the transsexual community, Psychopathia Transsexualis, until her death in 2014. Award-winning poet and academic Trish Salah, in her foreword, remember that Gendertrash “was a catalyst and a convening” for a broad audience of readers: “transsexual, transgender, MTF/FTM, Two-Spirit and genderqueer, sex workers, prisoners, poor and disabled folks, artists, grassroots activists of all stripes, service providers, anti-racist feminists, anti-imperialists, anarchists and more.” If only it had been able to have a wider impact still, perhaps we wouldn’t be where we are today, with trans rights being rolled back across North America and beyond, and with trans people, especially trans women and transfeminine people, being scapegoated for the myriad ills of late capitalism.

Such an impact is a lot to expect of one zine, of course. At the same time, the clarity of purpose and breadth of coverage in Gendertrash can’t be denied. Nor can its unmistakable, scorching anger: expressions of trans rage that its readers clearly had an appetite for. One letter to the editors admires the zine’s “generous soupçons of irreverent wit and self-righteous anger,” while another letter writer urges the editors not to soften, writing “don’t lose your edge,” and noting that the third issue seems “a bit less angry” than the first two. As well as being a space for trans rage, Gendertrash is a text that celebrates love between trans people; it offers so many accounts of trans solidarity, friendship, romance and support. “Who knew, back in the early 1990s, that trans people could love one another like this?” writes Tigers. A diaristic account of a middle-aged trans woman’s trip to Montreal for gender-affirming surgery includes her week of recovery post-surgery, during which she stays at the home of another trans woman who has had surgery herself and now hosts out-of-towners who have no one else to support them in the aftermath. “Imagine if I had been in a cold hotel room with no one to comfort me,” Norma, the diarist writes. “It scares me now to think of it.”

Interviews with Diane Gobeil, an HIV/AIDS educator at CACTUS, a Montreal community-based, harm reduction organization focused on STI and bloodborne infection prevention, and Dancing with Eagle Spirit, an organizer at the Vancouver Downtown Eastside’s High Risk Project Society, a trans-for-trans support group for street-involved people, make it clear that “by us for us” services for trans people, sex workers and people living with HIV/AIDS are paramount, in terms of actual care and support. Gobeil explains that she is appreciated by service users, because as a trans woman and sex worker herself, she isn’t asking “those stupid questions” that cis social workers ask. “When I go to meet a transsexual [to provide health services for HIV/AIDS], I’m not there to understand why she is a transsexual. I couldn’t care less ’cause I know why she’s a transsexual—I am one.” Dancing with Eagle Spirit notes that as a former addict and sex worker herself, she’s encountered a lot of shaming and prejudice from straight social service providers and is dedicated to providing trans-led alternatives.

Installments of the high-energy TSe TSe TerroriSm, a serialized novel by CaiRa, feature tender, supportive romantic relationships between trans women characters who are otherwise facing an onslaught of violence in their lives. After she is forced to kill several threatening straight men in self-defence, the sublimely named molotov cocktail evelyn ann is comforted by her girlfriend, Willow Trees in Autumn. Will Willow Trees still love her after she has committed an unwanted yet necessary act of violence? “Yes I will always like you and love you,” replies Willow Trees, holding molotov cocktail and stroking her hair. “Always without conditions or requirements.” molotov cocktail sobs on her shoulder, and eventually the two spend the night together in Willow Trees’s apartment, where they share “an Amazing Evening, a totally emotionally incredible one.”

In the non-fiction department of trans dyke bonding, Gendertrash features several in-depth accounts of the notorious exclusion of trans women from the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (MWMF) in the early 1990s, and the subsequent establishment of Camp Trans, a trans-led protest mini-festival outside of the MWMF’s entrance. These articles document the trans sisterhood that arose as trans lesbians from all over the U.S. got together to oppose the festival’s “womyn-born-womyn” policy and to provide education to the cis lesbian attendees. They gained a good deal of support and solidarity from said cis lesbian attendees—including protective escorts from the Lesbian Avengers—most of whom were far more open to trans inclusion than the organizers of the festival were.

In Issue 4, however, Christine Tayleur offers a critique of the Camp Trans movement, pointing out that the question of trans inclusion in a lesbian music festival was significantly less pressing than the fight for basic rights and resources for poor, racialized and imprisoned trans people. Tayleur, a San Francisco-based trans social worker at the time, warned of the return of right-wing ideology in the early 1990s. Trans people with racial and class privilege need to be making connections and sharing resources with less resourced trans community members, she writes: “The right is on the rise and nothing short of our very lives are on the line. If we are not helping the most oppressed members of our community, we are truly not helping anyone.” Her words could have been written today, with just as much resonance. Reading them now, alongside the rich spread of pieces that fill these pages, is both sobering and galvanizing. The fight is not over, and trans people cannot settle for mere tolerance and so-called inclusion in what these writers would call “genetic” spaces (“genetic” being the term for “cis” at the time). “You’re so busy looking at us, you can’t stop to think about some of the things we need,” writes kiwi, a regular Gendertrash contributor and researcher, in an article addressing cis academics. What trans people need is “progressive social policy, inclusive education programmes, support gender identity counselling.” If “genetics” can’t get with the program, they can “fuck off and die,” she concludes. This punk intolerance for liberal mediocrity should be inspiring to us now. Salah reminds us of Gendertrash’s importance both as an archive of a crucial era in trans activism, and also as a guide for the future, which must, unfortunately, involve a similar level of trans rage, purpose and clarity. “It is where we came from,” she writes. “It is also where we need to go.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra