“I am I, Lan Thao Lam, and I am Not-I, Lana Lin,” writes Lana Lin, in her brilliant new experimental memoir, The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam. This assertion, with its contradiction, its intimacy and its playfulness, is characteristic of the text as a whole. A queer Asian response to Gertrude Stein’s 1933 modernist classic, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam encompasses both a sense of kinship with Stein and her long-term partner Alice B. Toklas, and a strong critical position toward that earlier text. The result is a fragmented yet holistic portrayal of Lin’s and H. Lan Thao Lam’s lives leading up to and including their long-term relationship, spanning decades and continents, as well as personal and collaborative art-making. Their ongoing engagement with each other as artists and life partners, despite traumas from war and diasporic alienation, is at its core a deeply romantic story, perhaps all the more so because Lin, like Stein, is not prone to sentimentality.

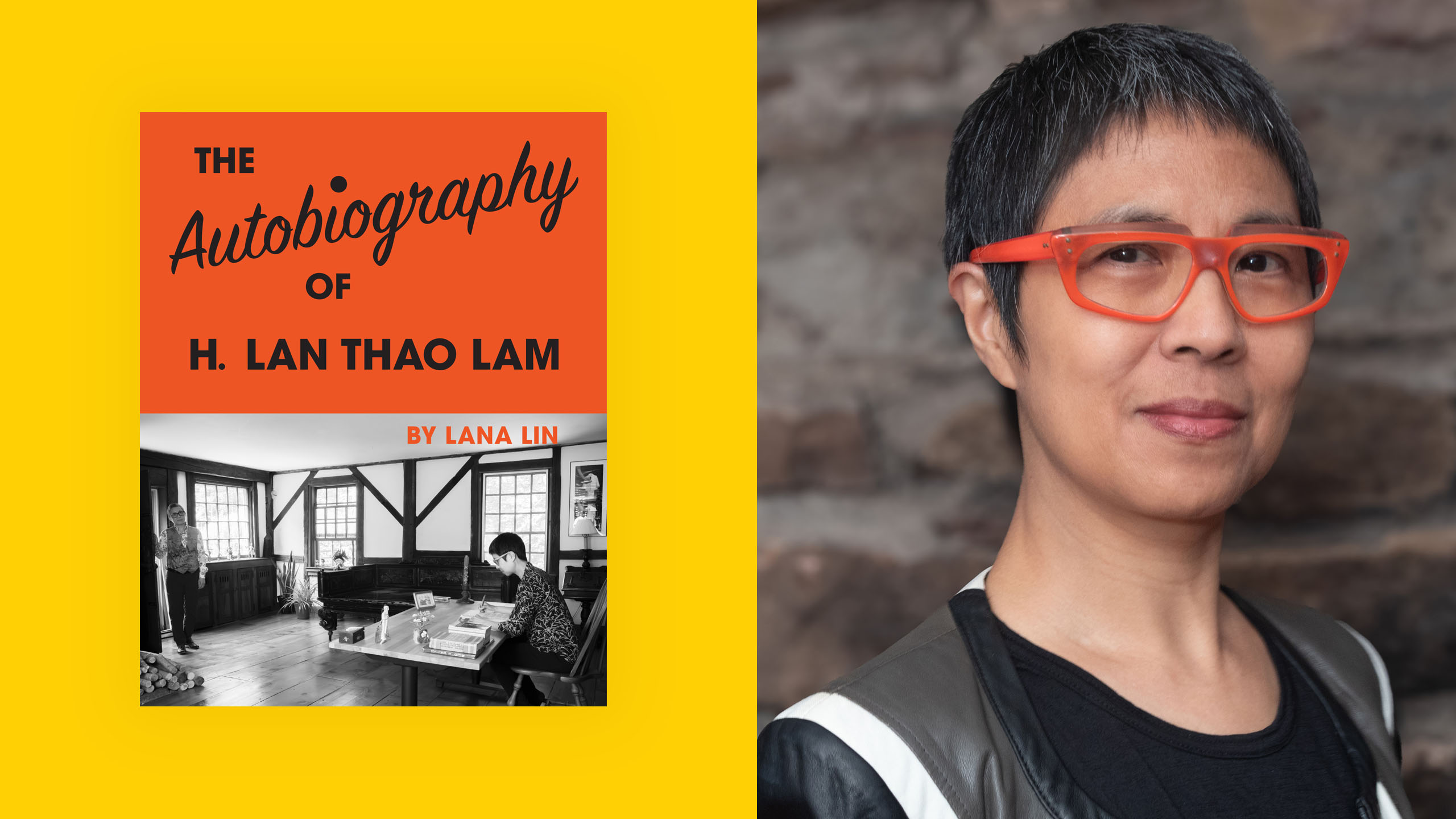

Lana Lin is a Taiwanese American multidisciplinary artist, filmmaker and writer; her partner, H. Lan Thao Lam is a Việt Nam-born artist, whose practice is grounded in research, object-making, installation, film, video, writing and performance. Both artists are queer and genderqueer. They often make art together as Lin + Lam with a focus on immigration, sites of residual trauma, national identity and historical memory. At the time of The Autobiography’s publication, Lin and Lam have been partners for 25 years, which was also the length of Stein and Toklas’s relationship when Stein’s book was published. The intimate conversation between Lin’s and Stein’s texts is evident before you even open Lin’s book. In addition to the echo in its title, its cover design also recalls that of the first edition of Stein’s book: the title is written in bold black type on an orange background, above a black-and-white photograph of the author, Lin, sitting at a writing desk, with Lam standing in the room’s open doorway, framed in light. Here, Lin sits in for Stein, while Lam stands in for Toklas.

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, which catapulted Stein to literary fame in the U.S. upon its publication, is a fictional autobiography, in that Stein, not Toklas, was its author, and, ultimately, its main subject. In addition to her slyly humorous, gossipy portrayals of some of the most famous artists of her era (Matisse and Picasso figure prominently), Stein, using the fictional voice of her long-term partner Toklas, writes her own life history. The book also traces the history of Stein and Toklas as a lesbian couple—two American Jews living in Paris before, during, and after the First World War. Lin replicates the structure of Stein’s book—the seven chapters in Lin’s text echo the seven chapters in Stein’s, except for some important name substitutions (e.g., “Gertrude Stein in Paris 1903–1907” becomes “Lana Lin in New York 1988–1999”), and employs Stein’s method of fictional autobiography. However, Lin’s book is a significant departure from Stein’s, both in Lin’s approach to portraying both herself and Lam, and in her overarching view of the world and its power structures.

Lin’s relationship to Stein and her work is ambivalent from the start. “The lives of Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein are remote from mine and Lana Lin’s in almost every way except that ours also revolve around the arts,” she writes as Lam. “Presumably we share our homosexuality as well, theirs as closeted lesbians and ours as openly gender nonconforming queers.” In writing the story of her life and Lam’s life, as well as their ongoing relationship, Lin is interested in “bringing the understory to the surface.” She writes against Stein’s and Toklas’s casual dismissal of the Asian people in their lives, for example. Stein and Toklas’s lack of regard for the Vietnamese cooks who worked for them was “an impetus for this book,” Lin writes. Lin’s text, which portrays Lin’s and Lam’s partnership as one of equals and collaborators, also pushes against Stein’s often patriarchal attitude toward Toklas, who is referred to in The Autobiography as one of “the wives,” placed alongside the female partners of the various male artists and writers who frequented the couple’s apartment in Paris. Meanwhile, Stein frequently referred to herself, using Toklas’s fictional voice, as a “genius.” In Lin’s text, and presumably in Lin and Lam’s lives together as partners and artistic collaborators, there is no genius vs. wife-of-the-genius dichotomy, just as there are no artists vs. cooks-who-work-for-the-artists.

Lin takes care to chronicle each partner’s life before the two of them met. As readers, we come to understand the importance of these earlier life experiences in forming the bond that the two artists now have. This is in stark contrast to Stein’s book, in which Toklas’s life before meeting Stein is largely ignored as unimportant. “A different shape to life formed with Lana Lin,” Lin writes, as Lam, “a shape that my Buddhist belief in past lives recognizes as having been formed before.” Lin’s text highlights how two kindred people, with their own particular histories, can become something new together.

In non-chronological fragments, we follow Lin and Lam from their first meeting at a 2000 New York City protest against the police killing of Amadou Diallo, through countless meals and walks together, through 9/11 and the 2003 SARS outbreak. Later, Lin and Lam take trips together to visit their past lives in Lin’s ancestral Taiwan, and in Malaysia, looking across the water at the refugee camp where Lam was displaced in their childhood, having fled Việt Nam in 1980. Lam and Lin navigate Lin’s cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatments; they move to different cities; they finish degrees and find academic jobs; they eventually are able to buy a modest house in which to settle more permanently. Lin does not write their lives as being more remarkable than other lives, the way that Stein, who is interested in her own self-canonization, does in her Autobiography. Lin’s text is more subtle, more concerned with the intimacy of mundane details, of how those details, especially the shared ones, slowly, miraculously accumulate into a 25-year romantic and artistic partnership. “We have crossed the borders of each other’s countries,” Lin writes, “each carrying our own solitude, yet surviving together for and because of each other.”

This project of surviving together is foundational to The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam; it is one of the reasons why Lin decided to write about herself in the voice of Lam. As the child of Taiwanese immigrants in the American Midwest, Lin grew up feeling like an “alien,” or like the “nobody” in Emily Dickinson’s poem, “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” Lin asks: “How to wade through the contradictions of suspecting that the very thing that makes you distinctive within a homogenous environment is what makes you invisible?” As a young Asian queer woman in New York, constantly being shoved, jostled, groped or flat-out treated like she didn’t exist in public space, Lin related strongly to the figure of the Angry Little Asian Girl, a cartoon character created by Lela Lee in the 1990s. Once they migrate to Canada and then the U.S., Lam feels this anger as well. However, for Lin especially, this anger is tangled up in the pressure to behave, to assimilate, to never voice her rage and even to suppress her own memories of things that have happened.

Lin invites Lam’s support to help her break through this suppression. In Lam’s voice, Lin writes: “Perhaps the prohibition against being singled out, or singling herself out … causes her [Lin] to suppress her memories. That may be why I am writing this autobiography.” Lam (as written by Lin), goes on to call themself an “autobiographer-detective,” referring to the process of writing about Lin’s life by perusing Lin’s archive of notebooks and other ephemera. There is an ouroboric quality to this assertion, of course, as Lin herself is the one writing it. “We don’t grow out of our anger, but if we’re lucky, we come to terms with it,” Lin writes. This very text appears to be part of that process: it tells and retells; it digests painful memories and turns them into stories; it breaks down Lin’s early feelings of loneliness and rebuilds them in partnership, with Lam as co-witness, and co-creator.

This collaborative approach to auto/biography includes Stein as well, though in a more ambivalent manner. The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam is an object lesson in how to remain in conversation with one’s artistic forebears, especially one’s problematic faves. On the one hand, Lin’s text owes its very structure to Stein’s. Lin also writes that Stein’s propensity for asking questions is foundational to her own practice of writing and art-making. On the other hand, Lin does not hesitate to name her criticisms of Stein and Toklas in the text itself. She writes of the couple’s racism, of their total disregard for the lives of non-white people around them, including those they employ. “Those of us who have been ghosted by colonial and imperial rulers may return with a vengeance to retrieve our histories, our own ghost stories,” Lin asserts. “We may rise up and rise and rise and rise.”

To pay homage to another writer, especially such a famous one, in the way Lin does here, with clear-eyed curiosity and appreciation without adulation, is an exciting project. The resulting text can teach us a lot about how we might relate to our elders, both in artistic and in political movements. Instead of either wholeheartedly emulating them or discarding them completely, Lin shows we can interact with their work with a twinned sense of kinship and of criticism, and always with an eye toward telling our own stories in our own ways.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra