In a telling encounter near the beginning of Naomi Kanakia’s latest novel, The Default World, Jhanvi, our protagonist, butts heads with Audrey, a member of the Fun Haus, a San Francisco collective house of tech workers where Jhanvi has been staying. Audrey, a white girl influencer and Google employee, is trying to kick Jhanvi out of the apartment, where she has been crashing for the last few days thanks to Henry, an old contact. In addition to being tech workers, the members of the Fun Haus run a sex party “that’s a little bit famous” called “The Guilty Party.” Audrey tells Jhanvi that things have been hard on the roommates lately, what with “the incarceration state. Racism. Injustice, people not getting it.” People all over the city are “being selfish, making San Francisco unlivable.”

Jhanvi herself is a second-generation Indian-American trans woman with no healthcare or housing: she is ostensibly one of the people whom the roommates are trying to be allies with—shouldn’t they be jumping at the chance to let her crash with them for free? Sure, she cares about injustice, but all she really needs is “a sandwich and a room of her own and a few hundred milligrams of estradiol and spiro.” Jhanvi will spend the rest of the novel trying to understand, befriend and manipulate this household of rich alternative-lifestyle, app-developer, sex-party-throwers into marrying her so that she can be added to one of their corporate health benefits plans, and finally pay for gender-affirming surgeries.

The set-up of The Default World is that of a classic adventure story: our heroine rejects a simple yet unfulfilling existence in order to risk everything in the wider, dangerous and unaccepting world beyond. At the outset of the novel, Jhanvi has just left her stable, boring life as a recently sober co-op grocery store worker in Sacramento to try to make it in San Francisco, where she hopes to access surgery. San Francisco is daunting—but she is ambitious and possibly deluded, and has showed up at the Fun Haus to ingratiate herself with her old college friend, straight guy Henry, who has agreed, sort of, over text, to marry her.

“The default world” is a term used by Henry and his roommates at the Fun Haus to describe a heteronormative lifestyle that they loudly reject. They are adamant about living a rebellious, alternative life, through polyamory, the Guilty Party and engaging in constant house meetings and processing—despite being mainly straight, white and cis, with Ivy League degrees. Kanakia, through Jhanvi, skewers the hypocrisies of this world view to hilarious and sometimes sinister effect. Henry’s dangled promise of marriage drives much of the book’s drama: if Henry marries Jhanvi, Jhanvi will be able to use his generous tech company health benefits to pay for her surgeries. But there is a snag: the two of them have been engaging in an intense sexting relationship that Henry will not acknowledge to his overlapping circles of friends, girlfriends and roommates. If Henry marries her, Jhanvi thinks she might finally feel some acceptance, perhaps even become one of his girlfriends. But Henry is worried about going public with her, and his friends are too obsessed with their own messy lives to care about Jhanvi and her situation.

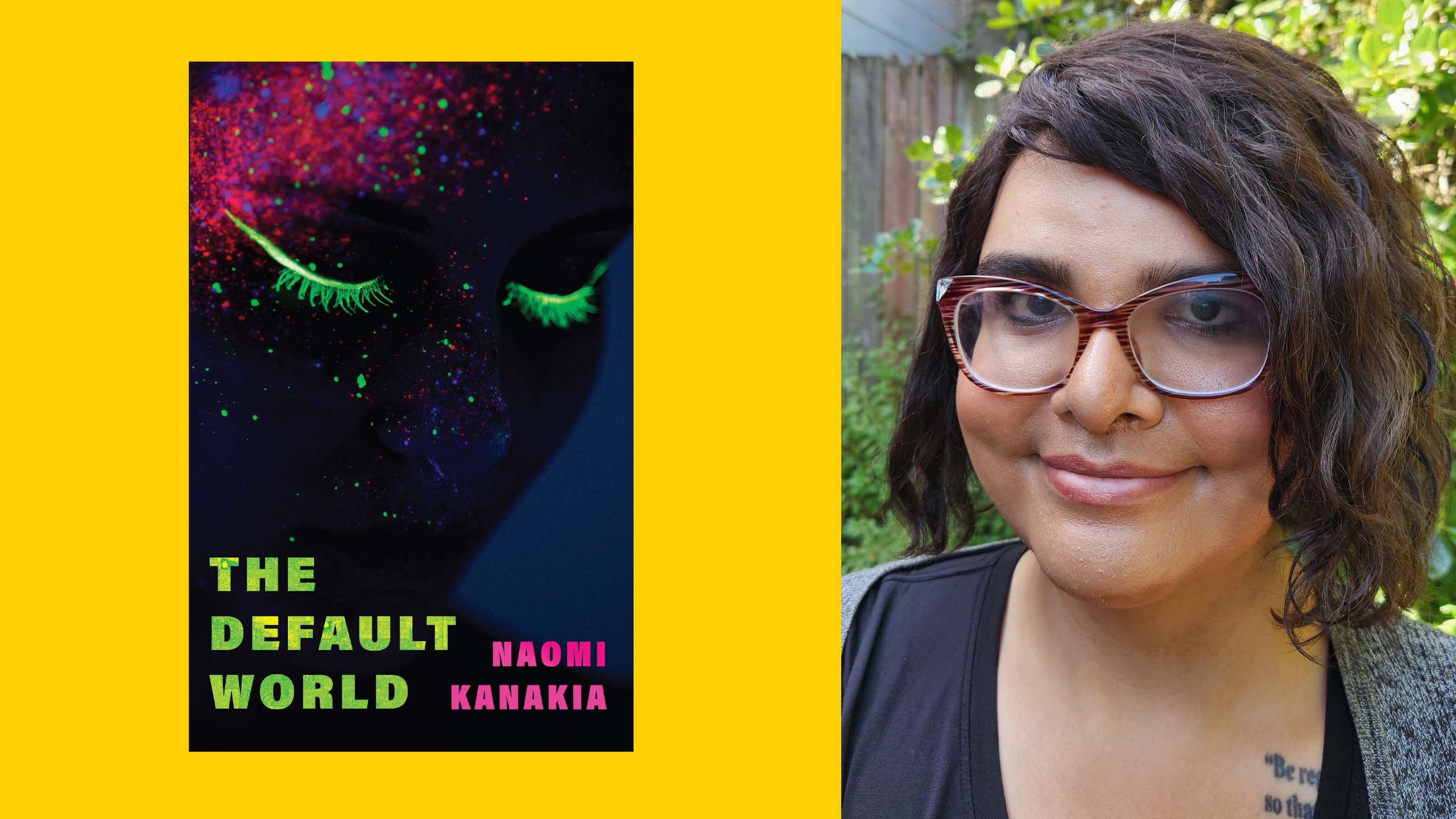

This is Kanakia’s first novel for adults—she has published three YA novels and a book of non-fiction to date. And The Default World is a decidedly adult book—it is scathingly funny, painfully realistic and relentlessly critical in its view of the world. Kanakia doesn’t cut her characters—or the reader—a break. Jhanvi brims with ugly feelings of envy, jealousy, despair, misanthropy and arrogance. She is no model minority, nor is she a model trans woman: she has terrible thoughts about herself and about other trans people she encounters. “Be the bad trans, be the bad trans,” she repeats to herself, like a mantra or a dare. Being morally upstanding, she has found, gets you nowhere. All of this makes Jhanvi compelling: we accompany her through humiliations and rejections, through lapses in both sobriety and judgment, privy to all her nasty, desperate thoughts. She is thoroughly human—largely driven by selfishness, but still capable of empathy and generosity from time to time. She isn’t a terribly good friend or a good person, but she does try to do the right thing when it matters most.

Surgeries, and the attainment of beauty and power, are Jhanvi’s ultimate goal for much of the book: she’s been on hormones for some time, but continues to struggle with intense feelings of undesirability and dysphoria, which result in both self-hatred and a sort of aggrandized misanthropy: “she was a parasite, a leech, a terrible person—and someday she would destroy them all.” She decides that she is an adventurer, by which she means a clever con artist, “tall, dark, and dangerous,” a risk-taker who will manipulate others to get what she wants. The Patricia Highsmith of it all! When she realizes that the members of the Fun Haus are not going to accept her as their friend because she isn’t white or thin or beautiful like they are, she resolves to exploit their hypocritical attachment to “allyship” into getting what she wants. However, it proves difficult not to get sucked into their beautiful, moneyed, sex-party-centric lifestyle.

A great strength of The Default World is that it lays bare questions of class difference and wealth disparities, and the internal and interpersonal conflicts that these differences create. Kanakia is committed to talking about money in her fiction: where characters get it, which characters have it, what jobs they work, what jobs their parents have, whether they have debt. In an article for LitHub, Kanakia remarks that while 19th- and early 20th-century novelists like Jane Austen, Honoré de Balzac, Edith Wharton and Henry James commonly wrote about their characters’ financial realities and motivations, the novel’s trajectory through the 20th and into the 21st century has seen money talk almost disappear from literary fiction, to the detriment of characters’ psychological legibility. “Money can’t be expunged from the text,” she writes in the article, “it can only be repressed, and in being repressed, these novels become the site of a neurosis that can be endlessly discussed but never quite explained.”

Henry and his roommates excel at repressing and deflecting money discussions. They all have Stanford degrees and high-paid tech jobs in 2010s San Francisco, which means they are also entrenched in the increasingly dramatic wealth disparity in the city. Henry, Audrey, Katie and their various lovers and acolytes twist themselves into knots in order to avoid talking about their earnings. Jhanvi, who is broke, is openly preoccupied with money and how to get it—she’s the one who needs tens of thousands of dollars for gender-affirming surgeries. She’s also the one who can see that the housemates are wealth hoarders, living in a rent-controlled, barely furnished apartment on their Facebook and Google salaries. At the same time, Jhanvi can acknowledge that her own class background is similar to theirs—they all went to Stanford, after all. Jhanvi’s parents are well-off, and, having gone to an Ivy League school, she has learned to speak the language of the upper class, and even how to turn upper-class insecurities in her own favour.

“Being in a marginalized position in society doesn’t make you a good person, we are reminded.”

Roshie is the one roommate who is neither white nor from an upper-middle-class background. She sticks out in the house—tolerated because of her high-paying job at Facebook, but never fully invited into the fold. Roshie is an Iranian-American cis woman who currently makes more money than any of the other roommates, but she grew up middle class, with parents who ran a grocery store. She doesn’t know the codes and values of the upper middle class, and is much more concerned with fairness, competence and honesty than her housemates—or even Jhanvi. At a turning point in the novel, as the power in the group seems to be shifting, Jhanvi realizes that, due to having gone to an elite college and “speaking the language better,” she has “leveraged her marginalization more effectively than Roshie has leveraged her wealth.” Meanwhile, Roshie is the only housemate who sticks up for Jhanvi and makes sure she can keep crashing with them. This should make Jhanvi and Roshie friends, but Roshie’s friendship is less sexy to Jhanvi than the approval of the other, less ethically minded roommates. Jhanvi observes that Roshie is an “outcaste”—the added e making clear the strict class hierarchies of this social world. Roshie is staunchly and unsexily middle class, despite her new money; Jhanvi knows that the group will never accept her because of this, and struggles with her own allegiances as she slowly gains power in the house.

Kanakia’s refusal to make her Indian-American trans woman protagonist “likable” is refreshing, and makes for an intriguing, often relentless read. Being in a marginalized position in society doesn’t make you a good person, we are reminded—this runs counter to the “we are allies to the oppressed” world view espoused by the Fun Haus members, who have a benevolent and dismissive idea of marginalized people as being ethically correct but ultimately unimportant. Jhanvi’s mind doesn’t give her much rest, and as readers, we get little respite from her negative thoughts and feelings. This full access to Jhanvi’s interior world is both delicious and challenging: it’s not that her thoughts and judgments are so rare, it’s that we might recognize our own abject reflections in them.

The thing with Jhanvi is that she knows her own moral weaknesses: she rails at the beautiful, white, admired housemates who don’t recognize theirs, who refuse to name the realities of their privileged positions, and worse, refuse to share the wealth and social connections that they pretend they don’t have, while using the language of allyship and inclusivity. In one memorable scene, we learn that the house’s WiFi password is “fuckthepolice,” which one of the roommates whispers theatrically to Jhanvi, earnestly explaining to her that they want to make sure people nearby don’t hear it and mooch off their internet. In another, Jhanvi tells Roshie that she knows that the other roommates could afford to pay for all her surgeries in one fell swoop, without even having to put her on their healthcare plans, but that they just don’t want to. “Imagine how much progress people could make if they just admitted the basic facts of what was happening,” she says to the other girl.

In The Default World, Kanakia is dedicated to the kind of harsh realism that Jhanvi respects. It’s not a particularly warm or forgiving text, but this means that its moments of levity and connection are hard-won and therefore ring true. It’s a smart, difficult, rewarding novel that requires some tenacity of its readers—and gifts them handsomely for it, with zinger after zinger of sharply observed, hilarious truths about millennial tech culture, allyship discourse, alternative living and making it as a trans woman adventurer in a cis-centric, bro-oriented, inhospitable world.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra