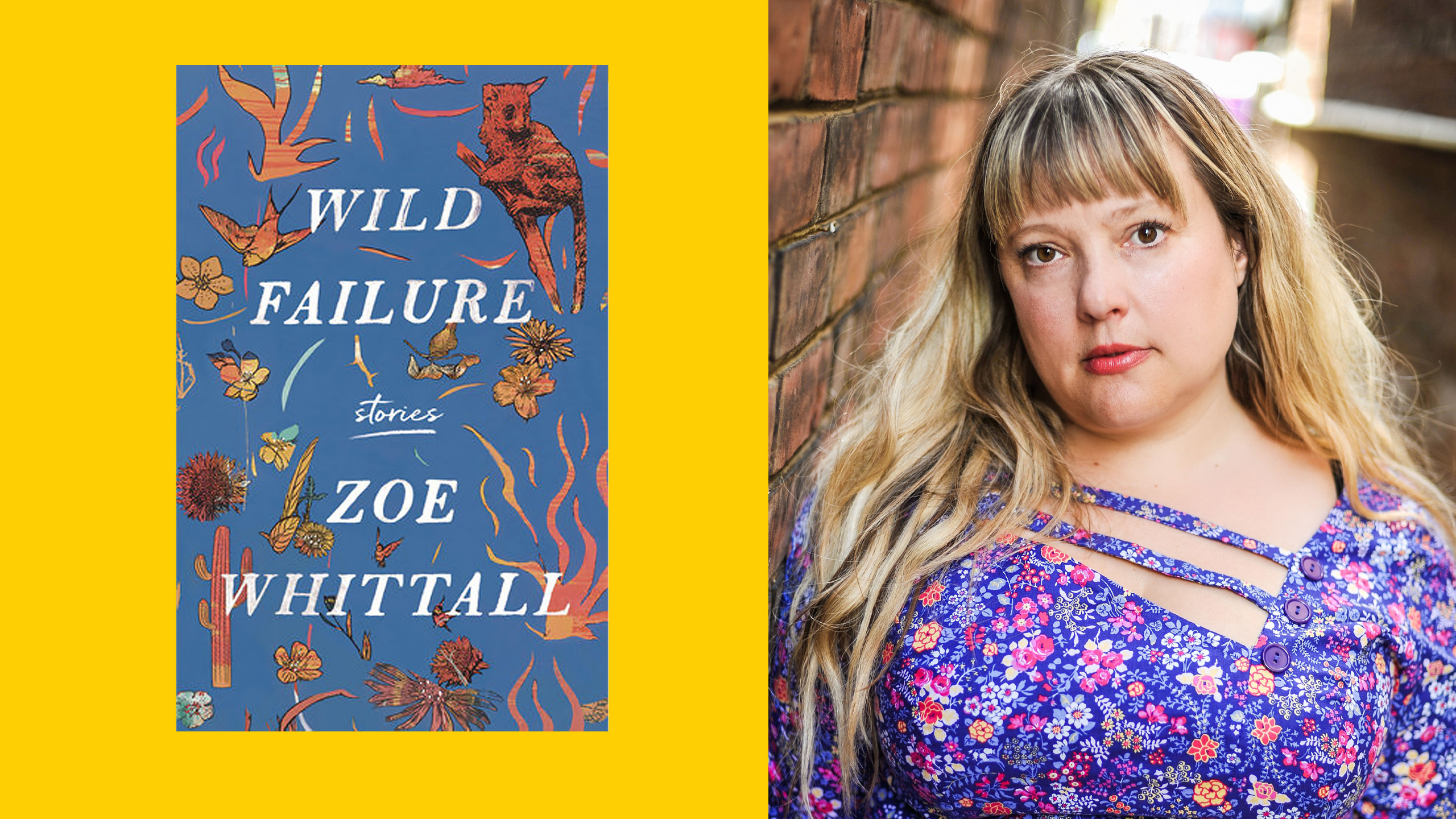

In her latest book, a collection of 10 short stories, Canadian bestselling author, poet and screenwriter Zoe Whittall offers readers a unique blend of dark humour and poetic realism. Wild Failure centres on female protagonists of different ages who challenge heteronormativity in their own ways. Drawing from her own experiences and those of others, Whittall captures the everyday lives of queer femmes and the nuances they face in navigating their sense of self, their queer identities, their relationship dynamics and their experiences with anxiety, sex and joy.

Through her characters, Whittall explores fear and “failure” in a way that feels deeply relatable.

Here, she speaks with Xtra about her short story collection, her personal involvement in the book, inspirations for crafting multifaceted queer femme characters, sex scenes and narratives that defy reductive heteronormative tropes.

Wild Failure is the title of both your book and one of the stories in it. Why did you choose this title?

The story “Wild Failure” is about a femme and a trans guy in a doomed relationship taking a road trip in the desert. She’s agoraphobic, and he’s a wilderness hiker. I was really interested in the idea of an agoraphobic trying to have a relationship with the wilderness when it’s her biggest fear. As a writer, I’m always interested and preoccupied with anxiety. I don’t actually remember the precise moment I came up with the title, but that was the element—the feeling of trying to have a relationship with the wilderness when you’re someone who finds comfort in ritual and sameness. What would it feel like to try to take on this epic adventure and fail? That’s sort of an encapsulation of that story.

I think, to a certain extent, most of the stories in the book have wildness—whether it’s wild escapes from convention or heteronormativity, typical life.

You’ve written several novels and poetry collections, but this is your first book of short stories. What made you want to work in this format?

I’ve always wanted to write short stories, but I felt more comfortable with novel-writing because novels are so expansive and there’s just more room to move around. I also found the constraint element of short-story-writing to be intimidating. But then when I finally wrote the title story, “Wild Failure”—which took me a number of years to write—I felt like a light went on and I knew how to play. If a novel is an entire ballet, a short story is just one pirouette. There’s so much precision involved, and so much on the syntactical level that you have to get right. I started to allow myself to feel like I do when I write poetry, and that allowed me to really sink into these moments.

Many characters in your stories grapple with their sexuality. In “I’m Still Your Fag,” the protagonist feels that her boyfriend Bob “rarely thought of [her] queerness” and she often had to remind him. Why was it important for you to challenge the notion of compulsory heterosexuality?

I spoke about this at my book’s launch in Toronto, actually. There’s this very rich and varied queer literary history. All of the books I write, in some way, are in conversation with queer books that have already come before. There’s a lot of knowledge about poetry and queer identity, but there’s not a lot of fiction with queer protagonists, so I felt like it was something that I wanted to be a little more explicit in writing about. Mostly because the form of a short story is so short, intense and passionate, and I wanted to convey exactly what I wanted to say. If I were to think of a unifying idea at the heart of the book, it would be a lot about discomfort or a feeling of disquiet about how it feels to be femme and queer. And a lot of the characters are bisexual as well. [So it’s] about kind of being a little bit invisible in a lot of ways, which I know is a cliché about femme identity.

I didn’t set out to write about a lot of femme characters, but it ended up being what I was thinking about, and what I felt was important in my own life. So that sort of ends up coming out in art, as whatever ideas we’re thinking about end up on the page.

In writing about femmes, you obviously explore the intersection between queerness and femininity.

A lot of people assume that femme identity [just comes naturally]. It’s sort of like, “Oh, I ended up here,” but there’s not a lot of thought behind it. I feel like there’s actually a lot of interesting specificity to the individual experience of self-discovery and self-confidence.

There’s a quote by [the lesbian writer] Amber Hollibaugh about how her idea of being a girl as a femme is watching herself be a girl, and there’s a space of irony. There are a number of moments in this book where characters are kind of negotiating how they’re perceived, how they’re witnessed and how they actually feel about their body in the world, or how people react to their body, their perception, or their presentation.

You touch on the pressure to conform to specific aspects of femininity after coming out. Can you explain why you wanted to focus on this in your book?

There’s this story in the book, “Half Pipe,” which is not a straight-ahead coming-out story—it’s about compulsory heterosexuality and a reaction to the violence of compulsory heterosexuality. The reader might realize the main character is in love with her best friend and is probably queer, but we’re watching her go through this intense high school experience where she doesn’t know why she doesn’t care about the guys she’s dating and doesn’t understand her feelings and how she’s acting. She’s sort of floating and noticing everyone around her having these quintessential coming-of-age moments, and she just separates from that. I think that’s the kind of coming out experience that a lot of femmes have. Not all of us have that feeling of, “Oh, I knew when I was three.”

I didn’t quite realize that I had written a story about compulsory heterosexuality until I was actually thinking about how I would have to talk about it to the press. A couple of reporters asked me if that story was about sexual assault, and when I heard that assessment, I thought, “That’s not quite accurate.” Even though that is the plot, it’s more about this kind of dissociative experience of being queer when you don’t know it when you’re young.

It’s easy to understand femme characters because you fully flesh out their thoughts and their actions. But it’s harder to understand the male characters with the same level of clarity. Was this intentional?

I think it was a choice because of the form. With short stories, you really have to sort of slice away at what’s unnecessary. The choices around a point of view and narration are often singular, and a lot of the stories are told in the present tense, so there’s this immediacy. Even if it’s a third person, you can only really know what’s happening to that person. I did really want to centre a lot of the femme characters because they were the narrators, but it certainly wasn’t intentional to flatten or not have full-blooded character defenders.

In one story, the narrator says about herself, “I could say bisexual but I don’t like that word. It conjures something I’m not.” Can you expand on this?

The character who says that is Teprine in “Wild Failure,” and she’s wrestling with having been in a relationship with a woman for many, many years and then falling in love with a trans man. I’ll speak for myself: there’s the experience of, whenever I’m in a long-term relationship with a specific gender, I often just call myself a dyke, and I do still feel that way, but I also date men. The character Teprine in that story was wrestling with this discomfort around the connotations of who bisexual people are because she doesn’t really identify.

Personally, I find that a lot of media and writing about female bisexuality often centres on a heterosexual lens. There are a lot of bi women who have been in the queer community for years and years, and sort of have a queer lens, and then there’s, like, discomfort from all around. I think a lot of bi women feel like if they date a monosexual person, there’s going to be a level of potential misinterpretation of who they are. I think that can result in an unstable sense of self sometimes, through no fault. It’s not inherent to the identity—it’s from the messages we receive around us. I think some of the characters in Wild Failure have really internalized those stigmas and are kind of wrestling with them emotionally.

In the book, we see characters having different types of sex, including straight sex. How did writing these scenes differ from others where characters authentically express their queer selves?

Yes, there are two stories. One’s called “Oh, El.” El is actually one of the straight characters, but her sexuality is a little bit kinky. And then there’s “I Need a Miracle.” Those are two of the oldest stories, and I wrote them before I had even written a novel, decades ago. Then I reworked them to make them better. There was a period of time when I would submit a story to a literary journal and get rejected, which is very common, and part of the career of any writer. But at one point, I decided to experiment with changing the characters to be straight to see if I would start getting acceptances. And it worked. It was so tragic. But then I ended up liking these straight women characters who kind of had a queerness to them, because that’s where the characters originated. The character of El is just such a funny little deviant character, a little burgeoning sociopath or whatever—she’s hilarious. I wanted to specifically explore a female character who was extremely hyper-independent, tough and emotional, to the detriment of her emotional well-being. I had a lot of fun with that story.

In terms of how to structure a sex scene, the process is very similar. There’s a way that sex scenes and text-writing, in general, can be hard or corny. Whenever I’m writing a sex scene, I’m really trying not to make it awful because it can become funny in a bad way very quickly. But I don’t think that the approach was any different, although there are certainly examples throughout the collection of sex that are less than self-actualized. It was different to write the scenes where the characters are fully present in their bodies and having a good time, and scenes that are more fraught. Writing sex scenes is an incredible artistic challenge; it’s hard to get right, and it’s an important part of life, an important part of queer life specifically. Right now, there’s a real skew toward a puritanical vibe in queer literature. I don’t think I intentionally wrote against that, but I do feel like that ended up being the end product.

I’d love to hear more about the move toward puritanism you’re seeing.

Well, I think in online culture. If you look at Goodreads, there are a lot of young readers who question the necessity of sex scenes. I think it is a failure to teach queer history properly to younger people. We see those ups and downs in culture. For example, even in my own life of being queer for 30 years, it was almost the end of the second wave where there was a lot of anti-pornography. When I was 16 years old, I was very against porn, and then suddenly, at 19, it was very important in the queer world at that time to have public porn parties, and I just sort of rolled with that, like, “Oh, I guess this is what it is.”

I think if we look back at the queer women’s community over the years, there are always these ups and downs between sex positivity and a different kind of feminism that boxes against that, so it’s not new. But I think what is new is the way literature is talked about in terms of what is important in art and whether sexuality is important. And I would say that sexuality is very important politically and artistically. I think that nothing good comes from denying that.

You include various relationship structures, including forms of monogamy and non-monogamy, but you also delve into the violence that can exist within them. Can you speak a bit about this?

It wasn’t intentional to have some monogamous relationships and some non-monogamous relationships. But I think that when you want to talk about a whole bunch of queer characters, monogamy is not going to be a given the way it is in straight stories. I just wanted to accurately depict that and part of doing that is depicting the reality of the funny moments and the discouraging moments so hopefully, there’s a variety of those.

Because people often focus a lot on sexuality, I almost forgot that there’s quite a bit of violence in the book. So yeah, that part was intentional. I think especially in “I Need a Miracle,” which is about Grateful Dead culture in the ’90s. If you weren’t around to see it, it was a culture of peace and community-building and all these kinds of philosophies that seemed very pacifist, but were actually kind of a violent culture. All in a very male-dominated way. When I started writing that story, I wanted to write about that duality. I’m always interested in cruelty and when it butts up against people trying to become who they are.

Many of your stories are set in the ’90s. Why?

In the ’90s, a lot of third-wave feminists were women workers getting into the sex trade. I think it’s always been the case that queer women have been in the sex trade—but I feel like there was a moment in time when people started talking about it or writing about it. This one character has this crazy experience with a customer, and I won’t spoil it, but the story is narrated by her at a later age as she’s going through some cognitive-behavioural therapy for her anxiety, and one of her assignments is to read obituaries because she’s trying to get over this fear of death and struggle with her mortality on a philosophical level. I felt like it was an interesting time to look back on that era of the ’90s. I was 19 when I came out and it was a really different time in queer history. I like to write about it because I think that there aren’t a lot of novels from that era that accurately depict what it was like, and I’m always sort of fascinated by trying to capture those moments.

You make various references to aging, particularly through the lens of queer femmes who wish they were still 20. Why was this a theme that you wanted to return to multiple times?

It wasn’t something that I intentionally set out to explore, but I feel like there was an awareness while writing a lot of the stories of my age. I’m on my 10th book and trying a new form. Also, I think that the characters, especially the queer characters and femme characters in the book, are wrestling with “What does our future look like?” You know, there aren’t a lot of examples of middle-aged and older queer lives, or there weren’t when I was 20. So it’s funny sometimes to arrive in middle age and think about it.

When I was 30 years old, I was standing in line—this was 18 years ago now—at Charlie’s, which was a nightclub in Toronto, and a girl in front of me, who must have been 20, said, “If I’m standing in line by the time I’m 30, kill me.” So, anyway, that comment was really funny.

What other femme writers should we be paying attention to?

I’d say, Adèle Barclay, Amber Dawn, Francesca Ekwuyasi, Jenny Fran Davis, Chloe Caldwell, Raechal Anne Jolie, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha and Farzana Doctor.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra