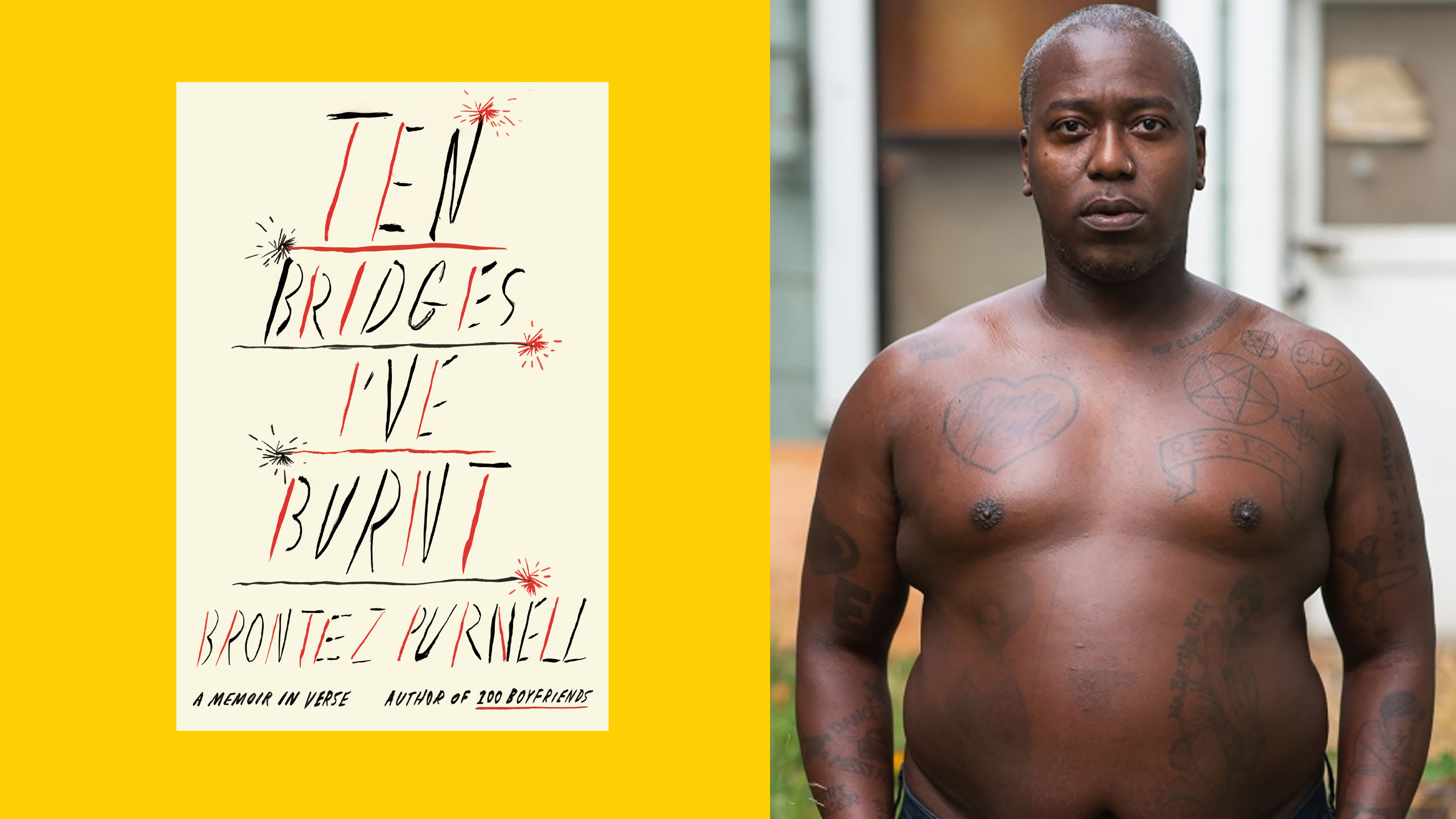

To experience Brontez Purnell’s art is to believe that he has lived a thousand lives in his 40-something years on earth. Purnell is known for his kaleidoscopic art practice, for being a disruptor and a lover, for turning heaviness into humour and for exposing the bleakness under what seems silly and light. He tells it like it is, whether through writing, performance, film, dance or music. He’s a longtime musician, having been the frontman for punk outfit the Younger Lovers since 2003; he also released a solo album, No Jack Swing, in 2023. He’s the founder of the Brontez Purnell Dance Company in New York. He started the zine Fag School after moving to Oakland from Alabama in 2003; he is a prolific writer and the author of Johnny Would You Love Me If My Dick Were Bigger, Since I Laid My Burden Down and 100 Boyfriends.

Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt is Purnell’s new memoir in verse, and fittingly for memoir, the most contemplative of his books so far. Readers of his work know him for his queer zine prose style—punk-show-length sets of short, frank, energetic anecdotes about hookups, touring, low wage jobs, friends and lovers, drugs, family trauma and making art against a backdrop of gentrification in the Bay Area. Always balancing on a knife edge between hilarity and despair. Never fear—that Purnell is still very much present in these pages; he’s just gotten a better paying job as a television writer, aged up to “auntie” status within his queer community and he’s considering ditching his bad habits of self-hatred and self-deprecation in favour of self-love: “this was my last ice age” he writes in the poem “NEWEST ROMANTIC.” “I’m thawing out/ my self-esteem is flooding the Earth.”

Though he treads these new pathways, the Purnell in these poems is still a beautiful mass of contradictions, still causing chaos where it is needed, still questioning himself and his motivations, still giving the impression of being in constant motion—which is enhanced by the way his verses run down the page, often in a series of two- or three-word lines.

The memoir’s first poem, “Oath of Athenian Youth” has Purnell upending any notions of autobiographical nostalgia for the author’s origins. There’s no rosy memory here, though the Grecian references might trick you into thinking there will be. “I was born in Athens (Alabama),” he begins, quickly cutting through any wistful thoughts of heroic mythologies. “I know nothing of olive trees and oracles/ only cotton stalks/ and rivers poisoned with DDT.” He remarks that Sparta is a more fitting Ancient Greek city-state to compare to the America he grew up in and continues to live in: “our gods study war/ subsequently/ I am bloody.” The nation-state he is interested in is not Greece or the United States of America, but rather his body: “the only city I have left/ is the one inside.” Purnell left Alabama in his late teens, and has lived in Oakland for the past 20-some years, immortalizing its many corners through his art.

Alongside the city of Oakland, the body has long been the site of Purnell’s writing—his sex writing is always embodied, concerned with the specific details of fucking—dick size, swallowing, barebacking, poop dick and other bodily excretions are often central to the emotional landscapes he fashions. In Ten Bridges, alongside the physical realities of gay hookups, he contemplates his own body—how it may be perceived by others, both in the past and in the present, as he reflects on what it means to be a queer Black man living in America. “I am a beautiful man/ I am only forty/ I could be your new husband/ but I’m overqualified for the job,” he teases in “Newest Romantic.” He is at once “a handsome Black man/ with a fat ass/ and a demonically expensive liberal arts education” and “as bloody as” the country he lives in and the violence it wreaks: as bloody as “The Gaza Strip; Ferguson; Laura Palmer; bloodstones; blood oranges; blood brothers; a Game of Thrones episode” and so on.

Purnell puts the blood and guts back into poetry in “TOMMY CHIN”—in which he recalls getting into a physical fight with the titular poet at the San Francisco Young Gay Poets Luncheon in 2004, due to said poet dissing him in the organization’s annual newsletter. The tone of the poem is characteristically funny and bitchy, but it gets at this deeper troublesome current of experimental literature and its barriers to entry, especially for racialized writers. “if I am not writing/ like someone’s favorite dead white man/ or even more insultingly/ like someone’s white-ass boyfriend” Purnell writes, he is told that he has no command of English. It turns out Chin has a strong right hook: “and he hit me again/ and now I think I’m in love with him?” This split second of desire is interrupted by the Purnell in the poem, who can’t help but humorously “give honor and respect to our positionality as/ men of color, Tommy” before hitting his adversary over the head with a glass pitcher, resulting in a lifetime ban from the Luncheon. Unbothered, Purnell feels justified: his actions demonstrated that at least for some, “poetry/ is still dangerous.”

Another potential threat that Purnell contends with throughout Ten Bridges is that of aging. While much of his previous work dwells exultingly in the present, these poems contemplate both past and future from the vantage point of an elder millennial “promiscuous gay man/ and/ toxic-ass bachelor.” In “Guy-o-logical Clock: Ticking,” he faces down the cultural pressure to pair up and settle down, grounding himself in the knowledge that he’s been “a damn good husband to himself” alongside raising all his friends. “My midlife crisis/ is the opposite of most men’s” he explains; he’s experiencing a slow cooling off rather than the sudden heating up that drives middle-aged straight men to buy expensive cars and cheat on their wives with younger women. However, the cooling off doesn’t mean that he’s waning: “well past my youth/ my body remains a hand grenade.”

In melancholic moments, he imagines a baby on his chest, worrying that something is missing in his life—should he have become a father? But he lets the thought go, though not without a tinge of regret: “there has only ever been me here/ and so it goes.” Later, more morose, he asserts that although men slightly older than him resent his “gentrification” of the term “old man,” “I am a man/ who is disappearing/ and on a molecular level/ my Black is cracking.” There is a sense of loss in these pieces. In one poem, he laments the demise of a queer ethos of togetherness that flourished in his twenties, communities of “Lost Boys” who acted as fathers to one another in the absence of biological family relationships, networks of intimacy that no longer exist for him.

“Purnell constantly makes and remakes his self-narrative through verse.”

With age comes perspective on parenting, as well. In “If I Had a Time Machine, I Would Kill My Parents …” he quickly qualifies the title’s pronouncement with the caveat that he would only “kill the version of my parents/ that is already dead.” Recalling their abusive parenting, he nevertheless maintains a softness toward them and their foibles: “oh my poor father/ all he wanted me/ to do/ was like pussy and shut the fuck up,” he muses, and then reflects that “paired against what he [the father] knows of the world/ my trauma reads as unremarkable to him.” He considers his own elder status in “AUNTIE,” resisting the societal narrative that encourages him to “talk shit about/ my baby siblings” who are “raging assholes” but also “blessedly poor and/ completely forgiven/ for all trespasses.” He considers the need to make way for the young and the new, without resentment.

Purnell constantly makes and remakes his self-narrative through verse. Anytime we might begin to assume intimate knowledge of Purnell through his contemplations, he reminds us that his memoir is not the vulnerable tell-all that it may seem to be; it’s written with a straightforward simplicity that may trick us into thinking it’s not precisely crafted, but this would be our mistake. “I look like the boy you would least suspect,” he writes in “And I Am Serving Fuck Boy Like It’s Going Out of Style …,” “when I walk down the street rest assured that I will not/ remember your name/ but more importantly/ rest assured/ that you don’t know me.” Later, he interrupts other assumptions we may make about the efficiency of his language: in “Inevitables,” he reminds us that though his thoughts appear “underdressed” on the page, “nudity need not represent sex/ but rather simplicity/ or truth/ and (perhaps most frequently)/ protest.”

Protest comes into play in new ways as Purnell navigates his new job as a TV writer (he wrote for seven episodes of the 2022 Queer as Folk reboot). Those accustomed to reading about his various encounters and hijinks at low-wage jobs (“jizz-mopper” at the strip club, weed reviewer at the pot club, “American waiter” at the diner) might be startled by his shift to the TV writers’ room, which seems cushy and perhaps boring in comparison. But he doesn’t spare this new working environment from his sharp observations. He knows he is expected to be “well-behaved, groomed” and to “shut my Black-ass mouth,” and that “every once in a while/ Hollywood pretends/ that it wants to hear what I have to say” but that nobody really wants to hear about him. He is often triggered in this workplace, transported back to childhood, when “even my silence/ was taking up too much space.” But he’s older now, further away from his days of starting fights at poetry readings. There is a melancholia to his realization that he now feels comfortable letting people expect very little from him, at least in the tepid setting of TV writing. The protest is doing as little as possible. In other poems, he’s still steadfast, stubborn, anything but passive: “Auntie (the old witch)/ has to fight/ until she dies.”

Purnell’s past work has a very in-the-moment quality to it: like a good punk song, his previous books give the impression that everything is happening in the present, in immediate, visceral, hilarious and haunting detail. In Ten Bridges, though none of the visceral momentum is lost, there is a sense of moving through time a little more slowly, a sense of looking back in reflection, of taking a breath, of leaving space between the words. At the same time, he’s ready to snap back into the present at any moment—we can get a little misty-eyed looking at the past, remembering how things used to be, but Purnell still isn’t one for dwelling; the moment we feel his verse slowing down and getting heavy, he speeds it up again, gives it a twist. A traumatic recollection, such as his father telling him in childhood that he was “born doomed,” is immediately followed by the wry assertion that “honestly, ‘doomed’ is just an easier place to operate from.” That Purnell is also a dancer, an artist of movement, is evident in Ten Bridges. He wants his words to have the “space to breathe,” and in these poems, they do; no longer packed into blocks of prose, they run down the pages in cascades, full of assertions, recollections, contradictions and challenges. He is an artist who can in one breath lament the fatigue of “the constant becoming/ the fact that/ every second was the future” and in the next, celebrate the fact that “the more I get fucked/ or fingered (triggered)/ the wetter/ and more receptive/ I become.” He may be aging, but he’s still hungry for living. The result is an incandescent poetic memoir, exultant even in its tougher moments, a surge of sound and motion that reverberates into the uncertain future.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra