“What can’t she do?” is a rhetorical question I’ve heard Vivek Shraya’s fans ask when discussing her. The multidisciplinary artist has a huge body of work spanning different genres, from music to literature, theatre to visual arts, film to fashion.

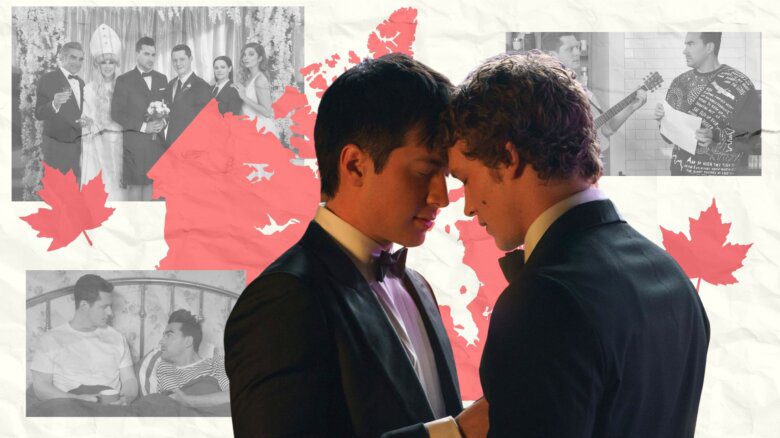

Shraya’s latest endeavour, How to Fail as a Popstar, is a fictionalized retelling of her coming of age. The memoir has had three lives—previously a hit play and subsequent book, audiences can now see it adapted as a limited series on CBC Gem. The TV series follows the character Vivek’s journey as a young queer Indian boy (Chris D’Silva) from Edmonton—who is obsessed with becoming a popstar—through the trials and tribulations he faces as a 20-something young person (Adrian Pavone). It is narrated by the 40-something trans author, artist and professor that the boy has grown into (Vivek Shraya as herself).

Shraya is a Canadian Screen Award winner and a Polaris Music Prize nominee; her bestselling book I’m Afraid of Men was heralded by Vanity Fair as “cultural rocket fuel.” It might seem contradictory then to learn that she made a show about failing. But what if our wins and losses in life didn’t overwrite each other?

The following contains some spoilers, but there are no dead giveaways.

Leather pants

Throughout the series, directed by Vanessa Matsui, we see that the protagonist is adamant to make it big. The teen Vivek—like the adult versions—will do whatever it takes. We almost believe he will succeed. But he is also adamant about one more thing. Making it big on his own terms. And it quickly becomes apparent that the character can’t have both.

We also see people in the industry trying to dictate how Vivek should be, pigeonholing the artist based on how they perceive Vivek’s identities and Vivek constantly defying those ideas.

In the second episode, “The Judge,” Vivek runs after one of the judges of the Youth Talent Quest, a singing competition that is held yearly at the mall, and asks her how he could improve his performance. “Have you considered wearing leather pants?” (like Ricky Martin or Freddie Mercury) is the judge’s response.

We see this unlikely advice thrown at him once more later in the show.

As I sat down with Shraya for an interview over the phone, I had many burgeoning questions. So, naturally, I decided to start with the most hard-hitting one. “How many times have you been advised to wear leather pants in real life?”

“Only once, but it scarred me,” Shraya says while out for a walk while visiting Toronto from Calgary.

Shraya tells me that, similar to her onscreen character, she had participated in mall competitions for years and could not figure out what the secret sauce was and how to get to the next level.

“Us queer people have to make ourselves more gay, more fabulous, for straight people to receive us. I think because of my ambiguity they didn’t know what box to put me in and they were like, ‘If you just fag out for us, we’ll know what to do with you. Just put on some damn leather pants,’” Shraya says.

Shraya, who is the creator and star of the show, points out the dichotomy this creates. “It’s interesting being an artist in a homophobic industry that simultaneously demands a certain kind of queer performance for legibility.”

Sitar player

In the third episode called “The Producer,”, we meet Matt G (Eric Johnson), the hotshot music producer who is going to make Vivek a popstar, or so he promises.

After a lot of back and forth between bright-eyed 20-something Vivek and the short-tempered producer, we hear the cursed advice. Thankfully, the narrator gives us a trigger warning.

“This song needs an ‘eastern flavour,’” Matt G says, imitating an Indian accent.

The producer is surprised to hear that Vivek doesn’t know any sitar players personally.

“When you’re marginalized at all times, you’re at the mercy of the mainstream receiver. And the mainstream receiver always wants you to lean into your difference. Lean into your trauma, lean into your exoticness. And so it becomes very hard sometimes to draw a line for yourself,” Shraya says.

Similar to character Vivek, Shraya has always felt strongly about one thing: perhaps donning a pair of leather pants and leaning into caricature sitar sounds would have been a lucrative move in the ’90s—both of which she pushed back against—because she wanted people to hear her for herself, and not because she’s “the spicy Indian artist,” Shraya tells me.

The episodes range from eight to 12 minutes and left me longing for more. I was invested in the talented cast and wished they got more airtime. Shraya tells me that the format is dictated in part by the broadcaster and in part by funding possibilities.

Yet, she took creating the eight capsule episodes as a “fun challenge.” Shraya is drawn to short form: her first book was a collection of short stories, and her songs are often only two minutes long. “For all my books, the spines basically don’t even exist. I love being as succinct and as efficient as possible,” she says.

“It very much is a queer story. It’s a bisexual story, it’s a trans story, it’s a brown story. But there’s nothing in Popstar that’s deliberately focused on these identities, or the difficulties and hardships that come with these identities.”

Watching the series, I found it refreshing how the characters don’t internalize the white gaze, which we don’t have many examples of in the media. It’s heartwarming to see that people close to Vivek—be it his mother or loyal, feisty best friend Sabrina (portrayed at different ages by Nadine Bhabha and Aayushma Sapkota)—love and support and respect who he or she is in that moment.

The characters are also not constantly at odds with their identity, which has become a somewhat tired narrative. In one scene, teen Vivek participates in singing bhajan (Hindu devotional songs) at the temple and feels like a celebrity when the aunties compliment his voice.

Representation has become a catch-all term that is sometimes devoid of meaning. In writing Popstar, Shraya, who just celebrated her 20th year as an artist, thought long and hard about it. “I do feel a certain responsibility to consider how to push it forward, like, where do we want to go next? And I feel so grateful to queer people who’ve come before me and the work that they’ve had to make and fight to make,” Shraya says.

It felt powerful witnessing brown normalcy on television. Not sticking out like a sore thumb. Of course, the world at various points reminds Vivek of the colour of his skin and his queerness, but the story isn’t only about that.

“It very much is a queer story. It’s a bisexual story, it’s a trans story, it’s a brown story. But there’s nothing in Popstar that’s deliberately focused on these identities, or the difficulties and hardships that come with these identities. It’s implicit, it’s there, but it’s really important to show a kind of queer trans brown experience that isn’t just limited to confusion or rejection,” Shraya says.

The show challenges the typical representation of South Asian families and what they look like, especially in the depiction of Chandrika (Ayesha Mansur Gonsalves), Vivek’s mother, who often steals the scene due to her tenacity and sense of chic style.

“I deliberately didn’t want a mom in a sari and a bun who is very submissive. I wanted her to be kind of a boss,” Shraya says. She further tells me how the character was loosely inspired by her mum, who “used to shop at Reitmans and was into shoulder pads.”

Shraya and I commiserate over how our brown parents wanted us to become doctors or engineers, but there is more to the story. “One of my biggest cheerleaders was my mum, who just really believed in the power of my voice,” Shraya tells me.

Hearing her say that reminded me of my own mum, who is possibly the biggest fan of my writing.

South Asian parents are rarely granted complexity in Western media. To see the onscreen mum first scold Vivek for asking her for $20,000 to record his debut album—“Who do you think I am, Oprah Winfrey?!” she exclaims, as is seen in the trailers—and later tell him that she’ll apply for a bank loan, was poignant.

“It felt really important to show a kind of brown parent that we don’t always get to see because not only has [my mother] been really supportive around my art, she’s also been really supportive, ultimately, in her own way about my queerness and my gender,” Shraya says.

On failing and seeking joy

We know going into the show that this is an anti-success narrative. “What if a star isn’t born?” the show asks us. There is immense discomfort in sitting with melancholy, but that’s what Shraya wants us to do, and writing this show is a way to push back against the ways in which society pressures us into resilience.

“I’m 42 and still rejecting the metaphorical leather pants and the metaphorical sitar,” Shraya laughs. She says she feels she has certainly paid the price for those choices. “In my artistic career, if only I had played into what the white gaze, the straight gaze, the cis gaze wanted, I do think my career might have been different.”

In a career spanning over two decades, Shraya is now making a show about not achieving her aspirations of stardom in music and is still making those choices and trying to embrace them. “You can only make the art you want to make and you can only be the artist that you are. At the end of the day, I’ve tried to make the best choices that I possibly can and who knows if they were the right or wrong ones. But clearly, I’m committed to them,” Shraya says.

As someone who has admired Shraya and her work for the past few years, I didn’t jump to console her and to remind her of her prolific portfolio as she talked to me about grief over an unrealized dream. Instead, I asked her if she is still trying to “make it.”

“Would I love for my music and my art to have a wider impact? And by ‘wider,’ I don’t mean whiter, I do mean wider. Absolutely! Is that my driving motivation in the same way as it was, in my teenage years, and my 20s? Not as much,” Shraya replies.

Shraya also says that these days she is trying to be happy and trying to find out who she is outside of her career and her work.

She recently joined a hip-hop dance class and confesses that she is bad at it. If you have seen her music videos, you’d be puzzled to hear this, because she sure can shake a leg and make it look seamless. “I’m so bad at it. And it’s so enjoyable. And it’s such a reminder, actually, that there’s joy in not being good at something. There’s joy in not turning something into part of my art practice,” Shraya says.

I saw Popstar as a form of reckoning—with her love for music and wanting to become a popstar against all odds, with her gender and sexuality, with being brown, with defeat.

I was curious if the show was meant to be a kind of closure, a sort of goodbye to the dream of becoming “brown Madonna.”

“A part of me will always feel sad and disappointed about what could have been. The show and the play, both were healing and cathartic in their own ways. But one of the things about failure, or heartbreak, is that I don’t know that a broken heart ever fully mends,” Shraya says.

How to Fail as a Popstar starts streaming on CBC Gem on Oct 13.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra