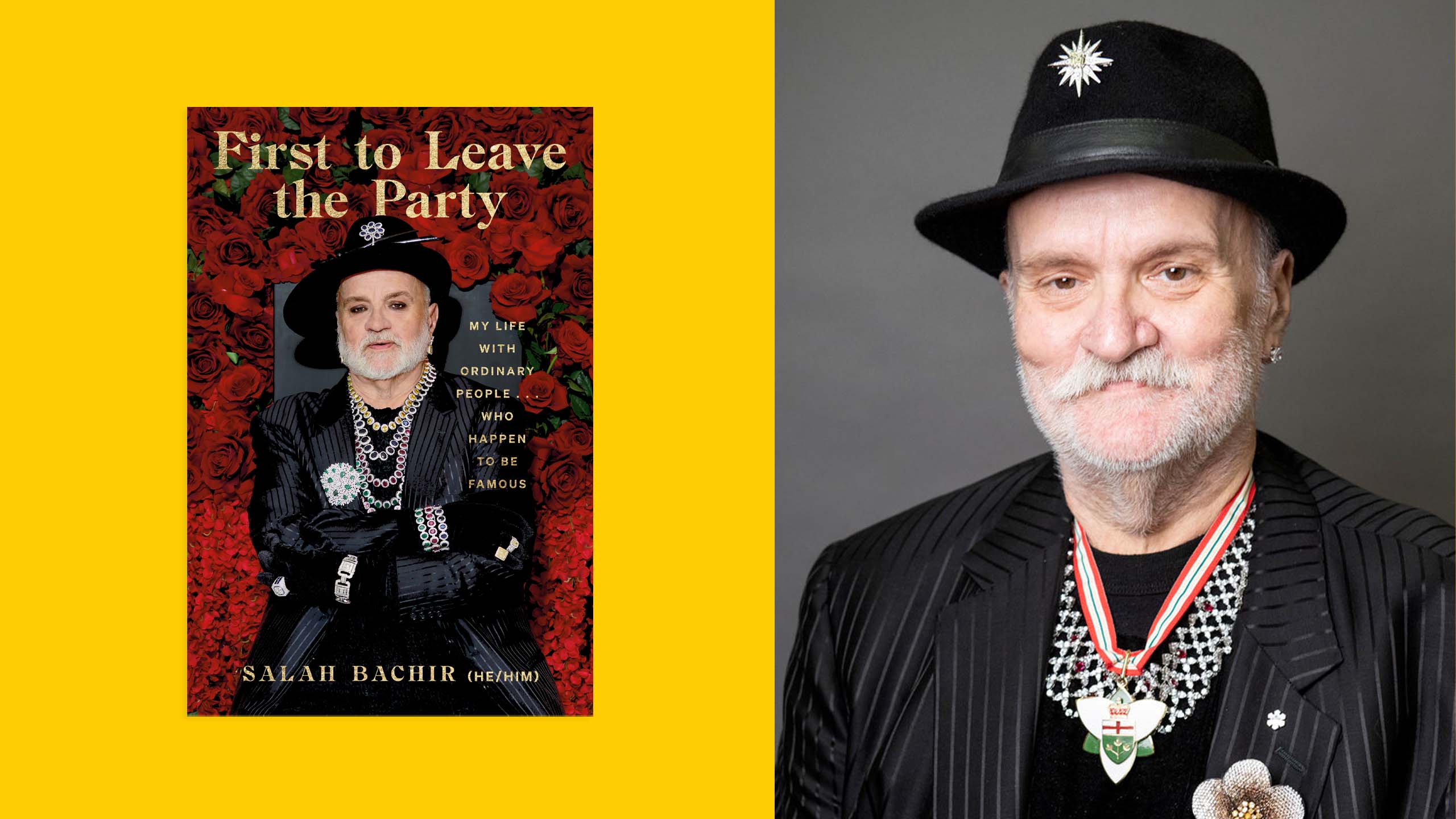

The first thing most people notice about Salah Bachir is his jewellery. The queer Canadian businessman and philanthropist is famous for augmenting his outfits with sparkling bangles, dangling earrings and multiple strands of pearls. On one level, his ostentatious look is a matter of practicality. At 68 years old, he’s never learned to tie a tie, and donning a broach for business meetings was easier than mastering a Windsor knot. While his flamboyant garb makes him stand out in a crowd, it also acts as a kind of shield, serving as a flashy middle finger to homophobes.

“There’s a fuck-you element in everything I wear,” Bachir says, laughing. He spoke with me over Zoom from the spacious Toronto condo where he lives with his husband, artist Jacob Yerex, and their Havanese dog, Max. “I don’t want to leave any doubt for people who see me at events or a younger person struggling with coming out, that this is a queer man.”

The desire to simultaneously attract and deflect attention characterized by Bachir’s personal style is also visible in his new memoir, First to Leave the Party. Written with film critic Jami Bernard, the book is divided into 54 short chapters, exploring Bachir’s life through a series of celebrity anecdotes; everyone from Paul Newman and Aretha Franklin to Eartha Kitt and Joan Rivers makes an appearance. Some of the stories, like his tale of brunching with Tennessee Williams, detail one-off encounters. Others, like the chapter on Ella Fitzgerald, explore lasting friendships. And occasionally, as in the case of Tallulah Bankhead, he dishes on stars he never actually met.

It’s an approach to personal narrative that’s both original in the world of memoir and familiar to those who know him. When asked questions about himself, Bachir often uses the story of a celebrity to illustrate a point. Glancing at the table of contents for First to Leave the Party, it feels like you’re in for a few hundred pages of inveterate name-dropping. But, like his penchant for ornamentation, the celebrities in the book serve multiple functions. In addition to offering tabloid-worthy anecdotes, each star’s life is used like a prism through which to view Bachir’s own.

That said, for a book being promoted as an autobiography, it reveals relatively little about its subject. We learn that he hates being called “Sal” and abhors when servers make wine suggestions unprompted. He was a party boy in his youth, but now calls it a night by 11 p.m. (hence the collection’s title). He briefly mentions his penis, in a story about hooking up with Keith Haring, when Haring is shocked to learn Bachir isn’t circumcised, despite being Lebanese. (His family is actually Greek Orthodox, not Muslim.) More than anything, First to Leave the Party is a rare portrait of the world of philanthropy, a space usually restricted to the rich and the famous—and those hoping to pry cash from their high-class hands.

When he first started cataloguing the encounters that make up the book, Bachir hadn’t intended for them to end up on paper. In 2021, he spent nearly six months in the hospital after a long-awaited kidney transplant resulted in sepsis. Wanting to maintain contact with the outside world, he began posting tidbits on social media, mostly chestnuts about A-listers that he would use to discuss his own experiences around body weight, the loss of youth or personal rejection.

“As I began to consider turning the material into a book, I knew I didn’t want to do a traditional autobiography where I simply recounted events from my life in sequence,” he says. “If I wrote this just about me, it would probably be only 10 pages long.”

Bachir’s tendency to minimize his personal history doesn’t exactly match the life he’s lived. After emigrating from Lebanon to Canada in 1965 with his family at the age of 10, he landed in Rexdale, a quiet suburb in northwest Toronto. ESL classes offered a way to connect with other local immigrant kids and indirectly led to his future path in the entertainment industry. The teacher encouraged students to perfect their accents by watching TV and Bachir quickly fell in love with the early ’60s sitcom Bewitched. Decades later, once he’d forged the necessary connections, he managed to meet Elizabeth Montgomery, the series’ star, who by then had become a key figure in the gay rights movement.

Although television was a key part of his youth, he was also an athletic teen, playing football and hockey in high school. (He remains a dedicated NFL fan today.) In his early 30s, he began gaining weight, something he attributes to a subconscious desire “to feel uglier to people” following a sexual assault. Along with his Arab ethnicity and being a long-term HIV survivor, his size has made him an outsider in queer environments for most of his adult life.

“The gay community is one of the worst spaces for body shaming, and social media has made it worse,” he says. “Gays fought to be included and then, once we started to achieve that, we began excluding each other. When you’re younger, you’re more impressionable and you take on that judgment. But I don’t really give a fuck anymore.”

After finishing high school, he enrolled at the University of Waterloo, where he penned articles for the student newspaper while studying history and political science. Then, in 1980, his life took a turn when his brother George opened Videoland, Toronto’s first dedicated movie rental store, and arguably the first in Canada. While working behind the counter, Bachir got the idea to launch a magazine that explored the fledgling field. When it hit the stands in January 1982, Videomania was the first consumer publication dedicated to this emerging technology. In addition to how-to guides and product reviews for home video machines, Bachir used the magazine to promote pictures that were hitting store shelves.

Despite Videomania’s nascent status, film studios made top-notch talent available for interviews, eager to boost profits in the burgeoning VHS market. This included celebs from recent hits as well as older actors whose films were being re-released decades after they were made. The magazine was both a way to cut his teeth in the publishing industry and a chance to meet bona fide stars. He would go on to found a slew of other cinema magazines and supported the launch of several home video labels, which together helped build his personal profile and his substantial wealth.

His entry to the world of philanthropy came, in part, through the magazine. Forging contacts with Hollywood luminaries meant he could call on them for fundraising events. As he notes in the book’s prologue, his interest in celebrities has always been less about the aura that surrounds them than what they’re able to do with it; Doris Day’s AIDS activism, Marlon Brando’s support for Indigenous rights or Margaret Atwood’s work on wildlife preservation.

It’s an idea he’s tried to exemplify in his own life. In addition to contributions from his personal fortune, he’s deft at rallying big-money donors behind charitable causes. His extensive philanthropic work has improved dialysis treatment facilities at St. Joseph’s Health Centre, facilitated significant renovations at The 519 (Toronto’s LGBTQ2S+ community centre), preserved wildlife habitat on Pelee Island and made major contributions to the art world, along with supporting numerous queer causes. Though much of this work is detailed in First to Leave the Party, it heaps most of its praise on the other people who helped make it possible.

“I’ve been a public figure for a long time, so I don’t think there’s much to say about myself that people don’t already know,” he says. “In reality, I find it a little uncomfortable being in the spotlight. I don’t want the focus to be on me. I want it to be about what our community has achieved together and what we continue to fight for.”

A memoir is always about legacy in some way; who is this person and what did they do for the world? With First to Leave the Party, Bachir is primarily focused on the second question. In moments where he might make a deeper observation about himself, he often deflects with a Hollywood morsel or a mention of his philanthropic achievements. It’s a tendency in line with his penchant for flashy accessories, and exemplified by one of the book’s best quotes, courtesy of Elizabeth Taylor.

“Sometimes all you need is to throw a stunning piece of jewellery on top of a plain dress,” she says. “They only notice the jewellery.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra