Sabrina Wu was in high school when, inspired by watching a standup comic on TV, they told their first official joke to peers at a dinner party.

“I told this story about the first time I tried to put in a tampon and how I slid it in between my two butt cheeks, and it just sort of sat there,” they tell me without batting an eyelash. Wu and their friends agreed that standup was cool; everyone assured Wu that they were funnier than the TV comic.

The second time Wu told that joke was a year later at a breast cancer research fundraiser held at Wu’s private and predominantly white high school in Ann Arbor, Michigan. “Half the crowd was clutching their pearls,” they say. “I was like, ‘Why did what I said gross people out so much? It’s comedy.’”

Two days later, their English teacher insisted on playing the clip of Wu’s set to the class, comparing it with a set from then-established comedian Ali Wong. Wu was forced to sit there as their classmates laughed harder at Wong’s material than theirs—most of the boys didn’t laugh at Wu’s set at all. Wu calls the experience “excruciating.” But they were determined to pursue comedy. The following spring, they enrolled in a talent show at a neighbouring high school and won. “It wasn’t competitive or anything, but it was cute and affirming.”

“Put that in there,” Wu later tells me. “I’m here to be reductive; I’m here to reduce, reduce, reduce culture into sound bites that are incendiary and funny.” It’s the comic’s way, they say, but it also feels like Wu’s way; since high school, they have struggled with being seen and with how much space to take up in a room, often downplaying their accomplishments—cute and affirming—as one way to avoid calling attention to themself.

“To me, it’s coming from a place of social awkwardness. I’m usually having a social breakdown because I am so afraid of bragging or being seen as narcissistic,” Wu, now 25, says.

Wu has earned some bragging rights, with a 2022 appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon; staff writing gig on an as yet unannounced Netflix series produced by Michael Schur, set for release in 2025; and original show script sold to 20th Century Studios. And of course their starring role in Joy Ride, the Seth Rogen-produced, Adele Lim feature comedy that was shot in 2021 and opened theatrically July 7. With its over-the-top crude jokes, which you could easily imagine being performed on a standup stage, the film seems like a natural bridge to Wu’s new acting career, and they’re already thinking about how they can improve.

The “Joy Ride” cast: Sabrina Wu, Ashley Park, Sherry Cola and Stephanie Hsu. Credit: Ed Araquel/Lionsgate

“It’s surreal to have something I did as a 23-year-old … being seen by so many people,” Wu says. “Even if the reviews are positive, I know I can do better in my lifetime.”

But Wu always returns to standup. Perhaps it’s where they are significantly less afraid of being seen. “I would want fame just so I could keep doing standup, but I wouldn’t want standup for fame,” Wu says.

Earlier this year, during a comedy set in the back room of Minami Lounge, a Williamsburg sushi spot that is occasionally home to the small, intimate Best Behavior: A Free Queer Comedy Show, Wu discusses their success for an audience of a few dozen people. “Yeah, I have this movie coming out, and I did The Tonight Show in the fall—umm, what are you all up to?”

They are surrounded by fairy lights, under a candelabra-like chandelier of large cork beads that looks as though it hasn’t been dusted in decades, as they go on to describe their post-Tonight Show experience.

“You sit on the couch, and you’re like, ‘Oh I should celebrate. You order Uber Eats, and then you’re sitting there, and you’re like, I’m a 20-something-year-old living in Brooklyn. I don’t have cable. How the fuck do I watch the Tonight Show!?”

Behind a microphone, Wu seems less concerned about how others might perceive them.

“It’s coming from a place where I get to tell the truth—be a dick—but you know that I know this is dickish behaviour, and I can do it.”

Wu, along with their younger brother, was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, to Chinese immigrants and raised in a bilingual household with an entrepreneurial father; their mother, who worked as a manager for Ford; and a grandmother whom they speak of with immense tenderness. Because Wu grew up oscillating between English and Chinese, they felt intimidated by unilingual English speakers whom they felt spoke more eloquently. This, coupled with a sense of being misunderstood as an out queer person of colour at the predominantly white Greenhills School, contributed to some of Wu’s sense of isolation and social discomfort.

In middle school, they would mimic the comedy they’d see on TV networks such as the Disney Channel, like pretending to drop their phone into the recycling bin at school so they could dive in, headfirst, to retrieve it with their legs protruding out from the bin, dangling in the air, waiting for someone to rescue them. In sixth-grade English class, when asked to tell a story about their weekend, they would exaggerate; they didn’t just fall in the shower, they fell in such a way that their hair ended up in their butthole, which they repeatedly dubbed “a woolly mammoth butt.” Sometimes they would drop down to the ground and army-crawl down the ramp in their school’s heavily trafficked hallway.

“I was a huge clown,” Wu says. “I’m hesitant to say class clown because they’re usually clever and witty, and I was truly like an idiot.”

When they first came out as queer in high school, Wu was bullied, so they stopped with the attention-grabbing gags; they found and embraced standup instead. Wu was involved in school activities and sports but sometimes their teammates would wait until Wu wasn’t present to take group photos. Other times, their peers would blatantly disregard what they said and gang up on them, calling Wu a “bossy bitch.”

They describe their high school environment as competitive, with many of their male peers unhappy with “a lesbian taking up a lot of space,” Wu says.

“I said ‘sorry’ every minute of my life,” they say. “I think that really scarred me. It’s a core reason why I’m still so afraid of being seen. I felt like I stuck out in high school, and I was so villainized for it and ostracized.”

Wu found the prospect of talking about their feelings and experiences through standup exhilarating. They thought comedy could help them become understood, and foster connections at home and at school.

“But [standup] obviously cannot fix those things,” Wu says. “And I was really sad to realize this thing I put so much effort into can’t fix my relationship with my family or make my mom be like, ‘We really see you now, and we’re so happy you’re gay,’ or, ‘Oh my god, look at all these people who love that you’re gay, I love that you’re gay.’ That’s not really going to happen.”

These days, Wu’s motivations have shifted. “Art is not for everyone,” they say. “It’s important to me that I don’t do art for the bros and people I don’t feel connected to. I hope it’s for people of colour to feel seen or people who feel anything like me, but I’m not trying to sell queerness or being a person of colour. If anything, I’m just selling the idea that you can do whatever you want.”

The spotlight, for which Wu has such intense ambivalence, is about to get a whole lot brighter with the release of Joy Ride. But Wu says they don’t want to go all “doomsday prep” and get their hopes up for how the movie might change their career and life. (Friend and fellow comic CV Sise suggests to me that Wu is “waiting for a shoe to drop” after months of anticipating the movie’s release).

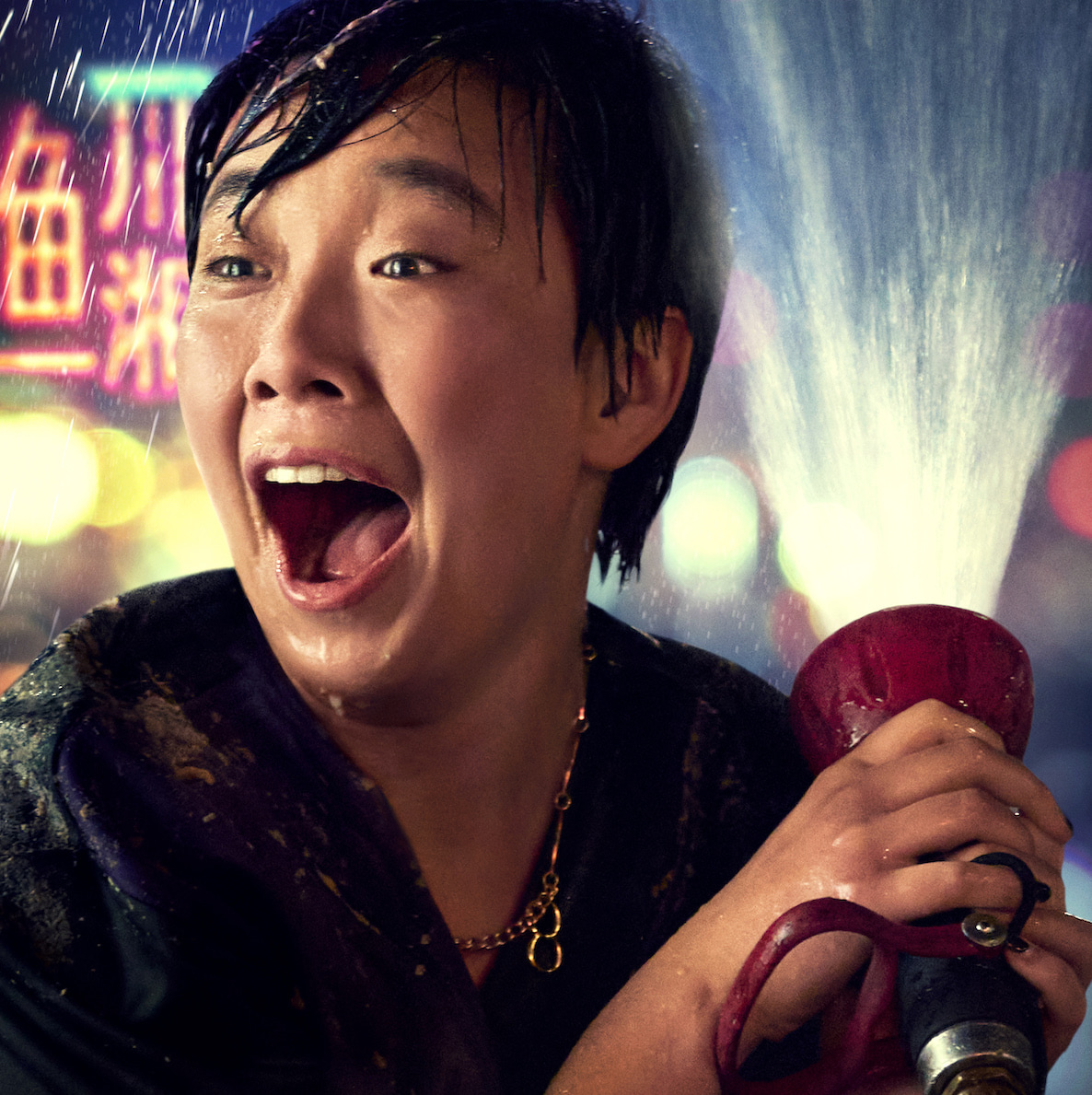

Wu refers to the movie, which was originally titled Joy Fuck Club, as a “stupid—in a nice way—studio comedy. It’s giving Asian Bridesmaids.” Joy Ride is the story of Audrey (played by Ashley Park of Emily in Paris), who travels to China on a business trip gone wrong that turns into a wild journey to find her birth mother. Friends Kat (Everything Everywhere All at Once’s Stephanie Hsu), Lolo (comic and Good Trouble’s Sherry Cola) and Lolo’s cousin, Deadeye (Wu), are in tow.

It’s a Hangover-like adventure that is outrageously funny, with plenty of sex (some even involving massage guns and basketballs), accidental drug smuggling and raunchy jokes. It’s also heartfelt, highlighting the importance of self-discovery and the beautiful chaos that is friendship. All the lead actors and their characters (save for Park and her character Audrey) are queer.

As Deadeye, Wu plays a Megan-in-Bridesmaids- or Alan-in-Hangover-type of outrageous character. One of Wu’s favourite moments is when Deadeye exclaims, “I’m not ready to have sex!” after being handed a condom filled with drugs. Instead of just being an over-the-top caricature, however, Wu worked to give Deadeye emotional depth. They constantly wondered what Deadeye’s motivation was, even when the character was doing something completely stupid, like expressing a desire to snort the powdered sugar candy Fun Dip. Wu realized that Deadeye was anxious and pretending to be a “cool person” as cover. That reminded Wu of themself as a former class clown.

A poster featuring Wu’s character Deadeye calls them “the chaotic one.” Credit: Lionsgate

“I imagined Deadeye was me at 12 years old if I grew up even more isolated than I did and never fully learned how to be funny in a more socially acceptable way.”

For Deadeye, being part of the journey to find Audrey’s birth mom is a huge deal. They long for friendship and true connection, and K-pop helps them find it. Wu shines when they, and the rest of the squad, make a crazy, impromptu K-pop music video, riffing off Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s “WAP.”

To audition for the role, Wu’s partner Jasiel Lampkin helped them film approximately 178 takes over a more than six-hour span of time. “I’m definitely in my trophy-husband era,” Lampkin tells me over the phone with a laugh. A few days later, director Adele Lim started following Wu on Twitter, and they got a callback soon after. However, the film’s creators debated cutting the character entirely, so Wu found themself going to a table read without a contract, though others had theirs, waiting to hear whether the character would remain in the movie and feeling extra pressure to nail the role. Once they got the part, the turnaround time was quick, and they were in Vancouver the following week to begin filming.

The role as Deadeye certainly lets Wu showcase their full range of talents—breakdancing, beatboxing, anxious and over-the-top jokes and surprisingly serious moments (like when a downcast Deadeye says, “No one wants to be my friend”).

The time they spent on set filming in 2021 was not easy for Wu, who was struggling emotionally, trying to understand more about their gender identity. They had never told anyone in a professional setting their preferred pronouns, and only came out as trans to their parents six months after shooting wrapped.

At the beginning of the movie, Deadeye is addressed with she/her pronouns, which shifts to they/them pronouns by the end—a subtle change that forms a significant part of the character’s development.

“Movies are so, ‘What do you want to wear? How is it we’re going to see you?’ I was just so scared, and I didn’t want to out myself as a total amateur,” Wu says. “So it was a huge learning [experience] the whole time we were on set.”

While they worried about coming off as “the weird one” offscreen because their character was so eccentric onscreen, they felt like their castmates, especially Hsu, really cared about and supported them, and the four stars had great group chemistry. So Wu was able to power through the difficulties, they say, particularly the emotional challenges of filming during that time.

Jes Tom, Wu’s friend and a fellow trans comedian (who is currently touring their solo standup show Less Lonely, presented by Elliot Page), says that Wu has sometimes come to them to share some of the hardships.

“You know, when I started doing comedy, I was doing this weird queer comedy about ‘they’ pronouns and stuff in straight comedy clubs, and I felt really alone for a long time,” Tom says. “So, I think it’s really amazing to see people like Sabrina really shine being honest to who they are and having a community [behind them].”

Wu is proud to be part of such an unusual Asian ensemble and its unique approach to representation. “This is a very funny movie for everybody; [no one wanted] to siphon it into niche race stuff,” Wu says. “We’re not trying to break the glass ceiling, but break the floor, if that makes sense—really promote Asian mediocrity. One writer has this really great line; she says, ‘Our movie is trying to bring dishonour to us all.’”

Since filming, Wu says they have gotten to the other side of a lot of inner turmoil. They are taking Lexapro, an antidepressant which, combined with therapy, has helped them embrace a new mindset. They are no longer focused on stalking their haters on social media platforms and trying to convince people who hate trans people to love their work, they say.

Reuniting with the cast a year after filming to begin promoting the movie, Wu had come to terms more with their gender identity and gained further acting and stage experiences, so they went in with increased confidence and, in turn, felt they were given even more respect.

In their personal life, too, the time since filming Joy Ride has been marked by change. After coming out to their parents as trans, Wu’s parents stopped talking to them for a while and then suddenly started talking to them again, but acted as though Wu had never come out. Uncertain of their reaction, Wu was filled with dread leading up to their Tonight Show appearance in October 2022. That didn’t stop them from leaning into the experience. Their set on the talk show includes a bit on coming out as trans.

“At some point I was like, ‘So, you know I’m thinking about going on T, taking testosterone.’ And my dad was like, ‘Okay, you don’t like your body, do you think I like my face? Do you think I like my skin, my eyes?’ He kept going. I had to pause coming out to be like, ‘No, Dad, don’t be sad, you’re so sexy.’”

Wu and their parents still haven’t talked about the appearance, or coming out, for that matter. But Wu did receive a text message from their parents after the Tonight Show. “We watched the show. You did great. Congrats,” followed by the party popper emoji. Wu reacted to the message with a heart.

The more Wu embraces being seen, especially with the release of Joy Ride, the more their mindset appears to evolve. At least to a certain extent.

“I don’t feel quite as, ‘I don’t deserve jobs that I’m getting!’” they tell me in June, five months after we first began speaking. “And you know I’m not terrible at what I do, or at least I have a lot of potential—maybe.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra