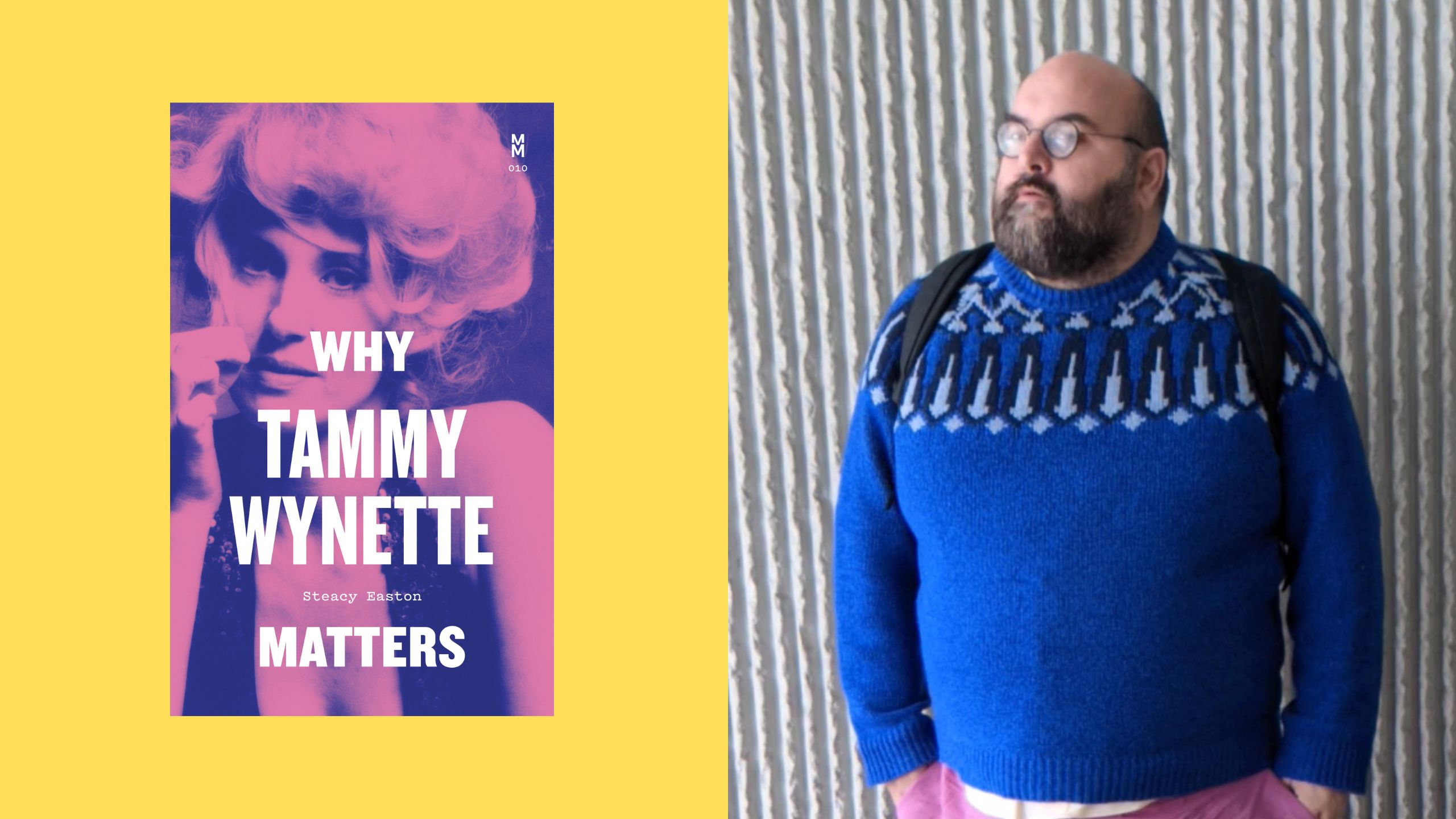

Country music rarely embraces queerness, and yet many of us feel at home with the genre. As Steacy Easton puts it, “singing through the suffering makes it better, but I also think there is a certain kind of relief in the genderfucking that can occur when a femme man listens to songs of female suffering.” The Hamilton-based author’s first book, Why Tammy Wynette Matters, was published last month as part of the Music Matters series of books with University of Texas Press, which make compelling arguments for why certain popular musicians are important. Country music icon Tammy Wynette was born in rural Mississippi in 1942. Though she was recognized far outside of country music circles for her songs like “Stand by Your Man,” she lived a tumultuous life.

Critic, academic and visual artist Easton was born and raised in Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta. For almost 20 years they’ve been exploring the ways that gender, sexuality, landscape and capital intersect in country music. This writing experience, combined with a passion for Tammy Wynette born in their teens, makes for important storytelling.

By age 17, Wynette was married, and she had three daughters by the time she was 23. Wynette’s life was riddled with chaos and pain; she found herself in five abusive marriages and struggled with addiction. In literature and media, her life often overshadows her music, even though she was the “First Lady of Country Music” and 39 of her singles landed on the Billboard country chart, with 20 reaching the top. She was and still is a country music icon and contemporary to Dolly Parton, Patsy Cline and Loretta Lynn.

Easton describes Wynette’s music as “first-person storytelling, a tight narrative of isolation and loss, a prioritizing of women’s pain over fecklessness, a voice that catches in the right places, and an arrangement that negotiates a territory between lushness and spareness.” Wynette sings about the expected themes of heartbreak and working-class life, with echoes of her personal domestic turbulence and loneliness throughout.

Wynette’s life story is often told through the stories of the men around her. Easton attempts here to tell a different version of her story; they centre Wynette and write about how relationships with her husbands and producers shaped her. With these men, she found song material, built up emotional armour, formed an image and built a career.

Do you remember when you first encountered Tammy Wynette’s music? When did you start to take her more seriously, to study her?

The first time I encountered her was my dad making fun of her when I was in my early teens. I got a high school assignment on “Stand by Your Man” for a module on country music, and I wrote about her then. I started writing about country music seriously in my mid to late 20s, in Toronto, a little bit homesick.

How did you arrive at writing Why Tammy Wynette Matters?

I knew that if I ever did a Music Matters volume, it would be on Wynette, because I thought she was important, and because I didn’t hear her being listened to or paid attention to. And because I had been working with her or about her since I was in Grade 12. Much of it comes to the ubiquity of Dolly Parton, and the resurgence of Loretta Lynn’s career and thinking that Wynette was under-considered. And then the things I am interested in—artifice, canonicity, public reputation, sex, money, gender performance, all flowed through Wynette.

Has country music resolved its problem with women? Are things any better for female artists today?

Country music has a weird tendency to push female artists and then punish them for their success. I think there might be a bit of an upswing, with the recent success of Lainey Wilson or Kelsea Ballerini, but for most of the last couple of decades, women in country music have been ignored, dismissed, kept off the charts and were more likely to be the subject of a track than its author.

You write about how Wynette’s interpretation and performance of her music bolstered the persona she was embodying. About how, the way she chose to perform her music—which notes she chose to sing louder or when she nodded to the camera or how she wore her hair and donned rhinestones were details of storytelling. And that her storytelling was as much about the words in the songs and the costumes she wore on stage as they were about her personal life and life choices. We know she was heavily managed and moulded by the men around her—husbands, producers, writers—and opposed to feminism’s second wave, but is this mythmaking not her own form of liberation?

I don’t know. I really don’t. Starting writing about Wynette I was hoping for some solid answers and I never got to them. She was born poor and ambitious in rural Alabama. She pushed her way up as fast and as efficiently as she could. She worked as hard as she could, in order to have some stability, and ended up broke at the end. This will sound cruel, but I wonder if Wynette’s seeking of liberation was mostly to liberate herself.

Are there contemporary country artists who use persona and make their life into art?

Every single solitary one of them, all of the good ol’ boy hunting, fishing and drinking that has gone on for decades. I would argue Jason Aldean’s trans/homophobia performs masculinity and class: rich people playing poor. That Morgan Wallen, who is the most successful recording artist in the U.S. right now, built the success of his career on the non-existent backlash of his racist and homophobic tirades. The weeping and the lashing out in Kelsea Ballerini’s divorce record, Rolling Up the Welcome Mat, this year is all high femme armour.

Wynette was conservative and publicly supported segregationist George Wallace; you address how her work sought to preserve the white American nuclear family. As you write in the book, she was part of a “white pushback against the rise of Black cultural power.” You also suggest that her most famous song, “Stand by Your Man,” may have been a response to Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique. Some of country music still assumes the role of asserting patriarchy, Christian values and white supremacy. What should country music’s role be today in dismantling these systems?

I’ll start this by saying that there are a cluster of Americana artists who are doing some fantastic work about gender and sexuality—the eros of Justin Hiltner, and also his gospel bluegrass; the folk singer Willi Carlisle; non-binary Adeem the Artist, who has one of the best voices in country right now; the queer women Brandy Clark and Ashley McBryde. Allison Russell and Joy Oladokun are both working with queer themes, as is Katie Pruitt—there is great, great country music made by and for queer people. Many of these figures are also making music at the margins of country. They aren’t making the big, brash, studio-dependent lavish and vulgar work Wynette was making in the ’70s.

All of that said—and this might mark me as old-fashioned—there are a lot of reasons why we listen to any kind of music, and I think that we are diminished when we expect the art we consume to pass a political purity test. I think that art whose purpose is just to do political work is propaganda—useful, but maybe less complex than it should be.

Admittedly, I get burned out on the cognitive dissonance, and there are artists who I just cannot listen to anymore; they tend to be younger than me, and I think to myself, well, they should know better, and there are artists where boycotting them is just easy work—I will not lose anything if I decide that Kid Rock is not something I will listen to.

I’ve jotted “was Tammy gay?” in the margins throughout the book. Maybe her broken marriages, her never not being in pain and what you call her “unsolvable ambivalence” were compounded by having to remain closeted. Am I reaching?

Yes. I think it’s possible to do queer work, and not to assume that someone is queer. All evidence suggests that Wynette’s exclusive erotic subject was men. Wynette’s persona as “tragic country queen” was about the tragedy of heterosexuality.

Wynette’s 1991 pop hit, “Justified and Ancient (Stand by the Jams),” a collaboration with British electronic band the KLF, is a campy, upbeat departure from the sadness and longing of her country career. I remember hearing this song on the radio constantly when it came out, but until now I had never seen the video. It’s completely absurd. Was this her nod to queerness?

There is a bizarre, and pretty amazing quote about the KLF meeting Tammy in Tennessee and making a complex crack about “Scottish Lesbians,” so I am absolutely sure that Wynette knew something queer (in all senses of the word) was going on with the KLF.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra