For fans of The Legend of Zelda game series, the opening moments of the newest iteration, Tears of the Kingdom, released May 12, are familiar. You play as Link, the frequently reincarnated hero of Hyrule, and after a brief section of cave-exploring with Princess Zelda, you wake up in a mysterious room wearing only underwear.

Like the previous entry, 2017’s Breath of the Wild, you navigate from this “room of resurrection” to reach an opening that reveals the game’s expansive and beautiful world full of towering mountains, hidden dungeons and hostile monsters. In Breath of the Wild, you were presented with two chests before venturing out to explore: one with a shirt and one with pants. In Tears of the Kingdom, you are presented with only one chest. Inside it is a single article of clothing—a skirt.

Link’s new outfit sent queer and trans fans into an absolute frenzy on social media. Playing the game’s opening hours shirtless feels like the pinnacle of the androgyny that has defined the character for decades. His small frame, long hair and elven features buck trends of normative masculinity that are abundant in other games, offering a softer gender neutrality that resonates with trans players especially.

This is by design. Zelda producer Eiji Aonuma told TIME in 2016 that he “wanted the player to think, ‘Maybe Link is a boy or a girl,’” referring to when the series first went 3D with Ocarina of Time in 1998. While canonically the character has always been male, Link’s design was intended to skew gender-neutral, a choice returned to with newer entries.

Breath of the Wild saw Link’s return to androgyny and was the series’ bestselling game by far, selling over 30 million copies and introducing many new fans to the franchise. Tears of the Kingdom is already on track to outsell its predecessor, having sold over 10 million copies in just three days.

Some players are celebrating Link’s appearance in Tears of the Kingdom as furthering the character’s gender-neutral expression. But others, like Sarah Stang, an assistant professor of game studies at Brock University west of Toronto, and game modder George Spacek, are asking more of the game’s developer, Nintendo. Stang, a lifelong Zelda fan, tells Xtra that in Japan, where the games are made, Link’s androgyny isn’t actually all that subversive.

“In Japanese popular culture, it’s very aesthetically appealing to have an androgynous man, like a pretty boy,” she says. “But in the West, we don’t really have that as much. We have a lot more of a masculine view of heroes because of our popular cultural positioning. Link already pushes back against that, [but] it’d be nice if it went a little bit further, just to do something a little bit brave.”

Credit: Nintendo

Link exhibits what Stang calls “masculine-skewed androgyny,” but he is still “unambiguously male.” His androgynous appearance is a product of Japan’s cultural aesthetic and his role as a silent protagonist rather than any actual progressive gender politics. “Link can be non-binary and still use he/him pronouns, but that’s clearly not what Nintendo’s communicating,” says Stang.

And while the games position Link’s gender expression as heroic, other forms of gender variance are often minimized, villainized or played for laughs. Queer-coded characters include the flamboyant Skyward Sword villain Ghirahim and Tingle, a clueless self-described “fairy” who appears in several iterations of the game. Even the titular Zelda, the franchise’s principal feminine character, is shafted into the role of damsel in distress in nearly every game, including Tears of the Kingdom.

The most egregious example is found in the franchise’s bestselling title Breath of the Wild, which includes a quest where Link has to buy an outfit from trans-coded character Vilia to enter the women-only Gerudo Town. Despite the fact that Vilia explicitly identifies as a woman, the game’s dialogue and quest descriptions frequently refer to her as “a man,” even prompting players with a dialogue option for Link to misgender her.

But the interactive nature of games offers players a degree of control over these story moments. In the case of Gerudo, dialogue options allow you to compliment Vilia rather than clock her, deciding for yourself how Link would respond. The ability for players to project their own identities and interpretations on to the characters and story is part of what draws queer and trans fans to Zelda games, despite some less-than-stellar representation.

Video games, says Stang, “are a queer medium, whether gamers want to believe that or not.” Moreover, the experience of playing a game offers a unique form of escapism that some queer and trans people appreciate. According to Stang, games like Zelda allow players to “escape to a world in which their body isn’t demonized, where they’re not discriminated against or where they can romance who they want without comment or persecution.”

In Tears of the Kingdom, players also have freedom in how they play and customize Link. You can follow the game’s suggested path of quests and dungeons, or you can choose to not complete them at all and play with the game’s building mechanics to craft your own creation, like a giant flame-shooting penis. You can dress Link in the most effective, high-defence armour or, as Stang puts it, “you can dress up like a total twink and just go around being like, ‘Yeah, I’m the hero, and I’m also gay as fuck.’”

But Stang also emphasizes that the interactivity offered by open-world games doesn’t mean players have total agency. “I think that there’s a lot of potential for what players bring. But I think we should be cautious to say that video games are the be-all-end-all because video games have also caused a lot of pain for queer audiences,” Stang says. “Whether it’s queerbaiting, or having an androgynous character, but then having transphobic jokes. I think there’s a lot of potential with video games, but I don’t want to oversell them.”

Limited by developer-imposed constraints, Stang says that one way players can exert actual agency is by altering the game’s code and creating what’s called a “mod,” a new version that truly transforms the gameplay and story.

George Spacek, who uses a pseudonym online to protect his privacy, is one such Zelda fan who took queering the games into his own hands. After completing the base version of Breath of the Wild in 2020, Spacek started playing around with mods and remembers one in particular that inspired him to create his own.

In the mod, the player character’s appearance is changed to look like Zelda without altering the in-game dialogue. “I liked playing as Zelda and being referred to as a dude, being referred to with he/him pronouns,” says Spacek. “Eventually, I was like, maybe I can try something like that … letting people choose their own pronouns for Link.”

It took Spacek a year and a half to learn how to code, develop and release the mod, explained in its online description as “a proof-of-concept for how non-binary identities may be incorporated into the world of Breath of the Wild.” Since it dropped in September 2022, Link’s Pronoun Wardrobe has been downloaded over 1,300 times.

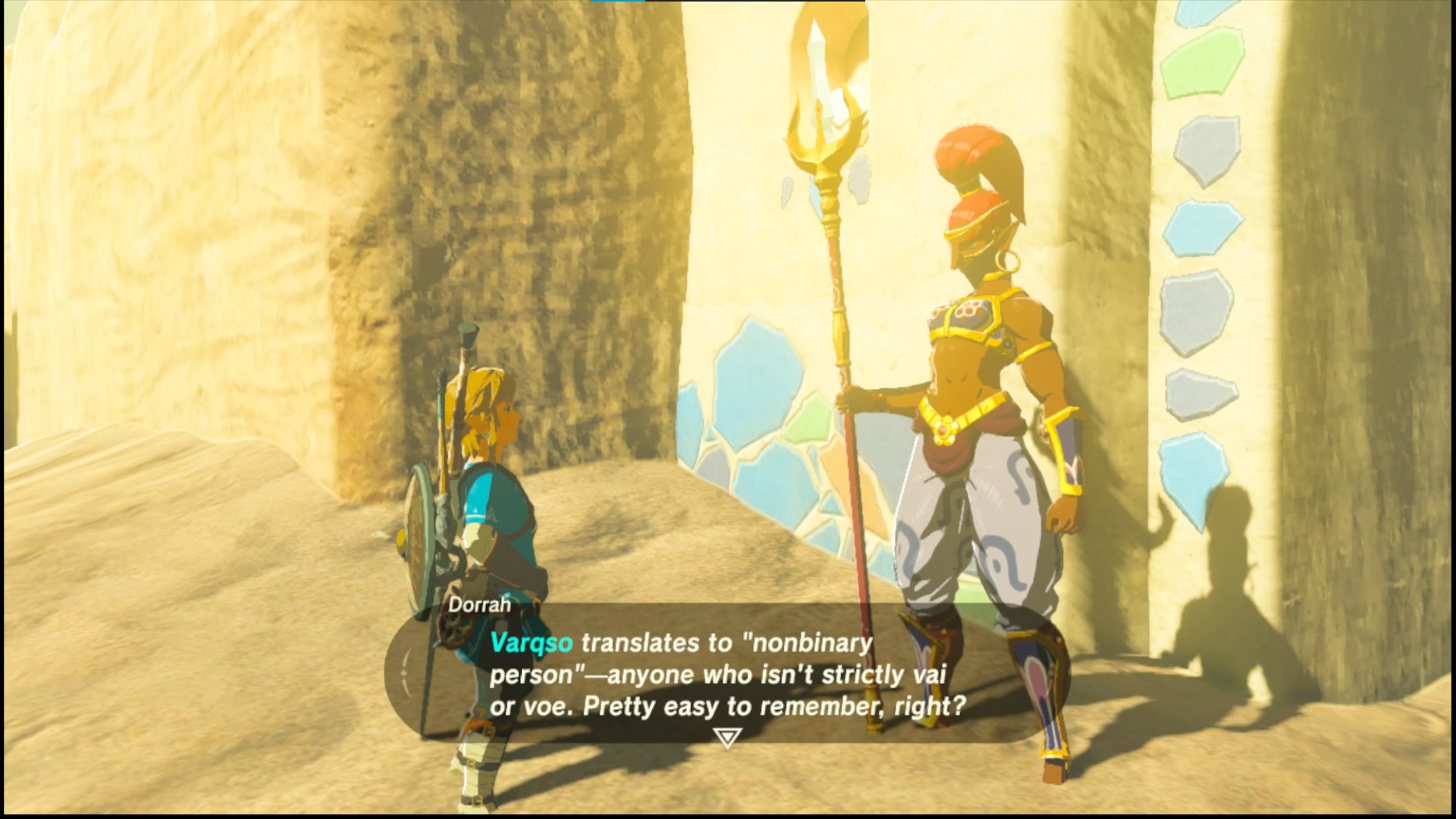

Along with allowing players to customize Link’s pronouns and gender, the mod adjusts the game’s dialogue to eliminate references to binary gender. When tackling the Gerudo section, Spacek opted to change the town from excluding those seen as men to excluding those seen as “unfashionable.”

In Tears of the Kingdom, Gerudo’s gender troubles are somewhat resolved when its revealed Link is permitted entry into the city, even as a man. But characters within the town will still express shock at the presence of a “voe” (what the Gerudo call men), something Spacek plans to address in a future mod.

“If you approach the town as a non-binary person or as a girl, I really wanted to challenge that mindset and make sure that, just across the whole game, not just Gerudo, but also anywhere else, any other NPC [non-player character] who’s talking to you, no matter how you are dressed or anything, your gender is not questioned,” says Spacek.

Credit: Courtesy of George Spacek

Spacek has created other mods that queer Breath of the Wild, ones that supply Pride T-shirts, top surgery scars and nail polish for Link—the latter being something actually offered in the base version of Tears of the Kingdom. He plans to create similar mods for Tears of the Kingdom, but hopes that for future Zelda games, he won’t have to.

“Heck, I’ll say it. I think it would be cool if we could change the pronouns [in the base game].” Spacek says that since Link is already quite androgynous, his appearance wouldn’t even have to change. “What changes are the gender and the text and having other people refer to you as such.”

No matter how gender nonconforming Link’s outfits are, the true queer power of The Legend of Zelda lies with its fans. As Spacek’s mods demonstrate, the potential for Nintendo to embrace this queerness is ripe for the taking.

Stang hesitates to get her hopes up. “I don’t see Nintendo embracing that, partially because they’re a Japanese company and in Japan there’s still a lot of regressive politics around gay rights and very traditional gender roles.” Still, Stang encourages queer and trans fans to continue to play Zelda games while challenging their gender essentialism.

“You can absolutely be critical of the media you love,” says Stang. “We can talk about how we love Breath of the Wild, how we love Tears of the Kingdom, but let’s not stop demanding that Nintendo do better, do more, right?”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra