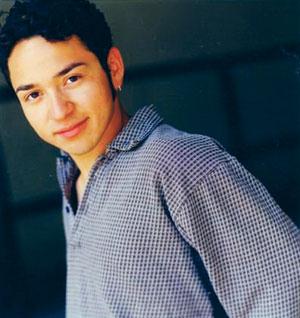

José Arias was arrested while in drag (as his alter ego, Dyna Thirst). The experience provided fodder for his new show, Arrested.

José Arias has been arrested twice, but only once in drag. Cabbing home from an AIDS fundraiser where he’d performed as alter ego Dyna Thirst, the writer/performer blacked out when his tequila caught up with him. Toronto bylaws require police to be called when a woman falls unconscious in a taxi. Not realizing Arias is a man (he stands a mere five foot four and is slightly built), his driver dutifully notified authorities.

The rest is blurry, but Arias came to in a jail cell, dishevelled, untucked and with a splitting headache.

“When police see a drag queen or a transsexual they only want to know three things,” the Randolph Academy graduate says: “if she’s a hooker, if she’s a dealer and if she has real tits. I don’t remember what happened, but during testimony it came out they had strip-searched me. They also tried to pull out my earrings, thinking they were clip-ons, and apparently that’s when I hit one of them. This wasn’t a case of law enforcement doing anything for the public. They just wanted to see what some little faggot had to offer.”

Fortunately, the arraignment judge scoffed at the notion of Arias assaulting three burly officers, instructed him to apologize and sent him on his way. Despite being a miserable experience, the process provided fodder for his first play.

Aptly titled Arrested, the semi-autobiographical work follows Ricky, a young Latino male finding his way after his mom tosses him out because he is queer. Though he didn’t set out to write about race, it became part of the work because of its place in his own story.

“Ricky keeps getting in trouble, but he never really does anything wrong,” Arias says. “It could be a matter of wrong place/wrong time, but there’s also the element of ethnicity. A lot of this play is about how the police treat people. I know firsthand how it can be, and I don’t think my experience is unique. It seems like every Latino male has been arrested at least once.”

Despite a rebellious youth, Arias has settled into a rather quiet existence, working in real estate between acting gigs and volunteering with various charities.

“My day-to-day life is pretty boring by comparison,” he laughs. “When I was a street-kid shit disturber, I was an easy target for law enforcement. Now that I’m a relatively respectable upstanding citizen, I’m not on their radar anymore.”

Though the relationship between racial minorities and law enforcement is a key element, Arias sees the personal journey of self-acceptance as the core of his script.

“More than anything it’s a play about self-forgiveness,” he says. “Being gay and Latino means having to forgive yourself in so many ways: for not being the son your parents wanted, for not living up to the expectations of your community. And at a certain point you also have to forgive yourself for your own internalized homophobia that’s a product of being raised in that kind of environment.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra