Much has been made of the stereotypical “bad gay” in pop culture—the villainous, depraved, queer-coded characters who have populated movies since the days of the Hays Code, which banned all overt depictions of homosexuality on screen. Should the tired “bad gay” character be abandoned, or does this lead to the opposite problem: overly sanitized portrayals of “good” queer characters whose decisions and actions end up skewing close to the straight-world values that queerness is supposed to subvert?

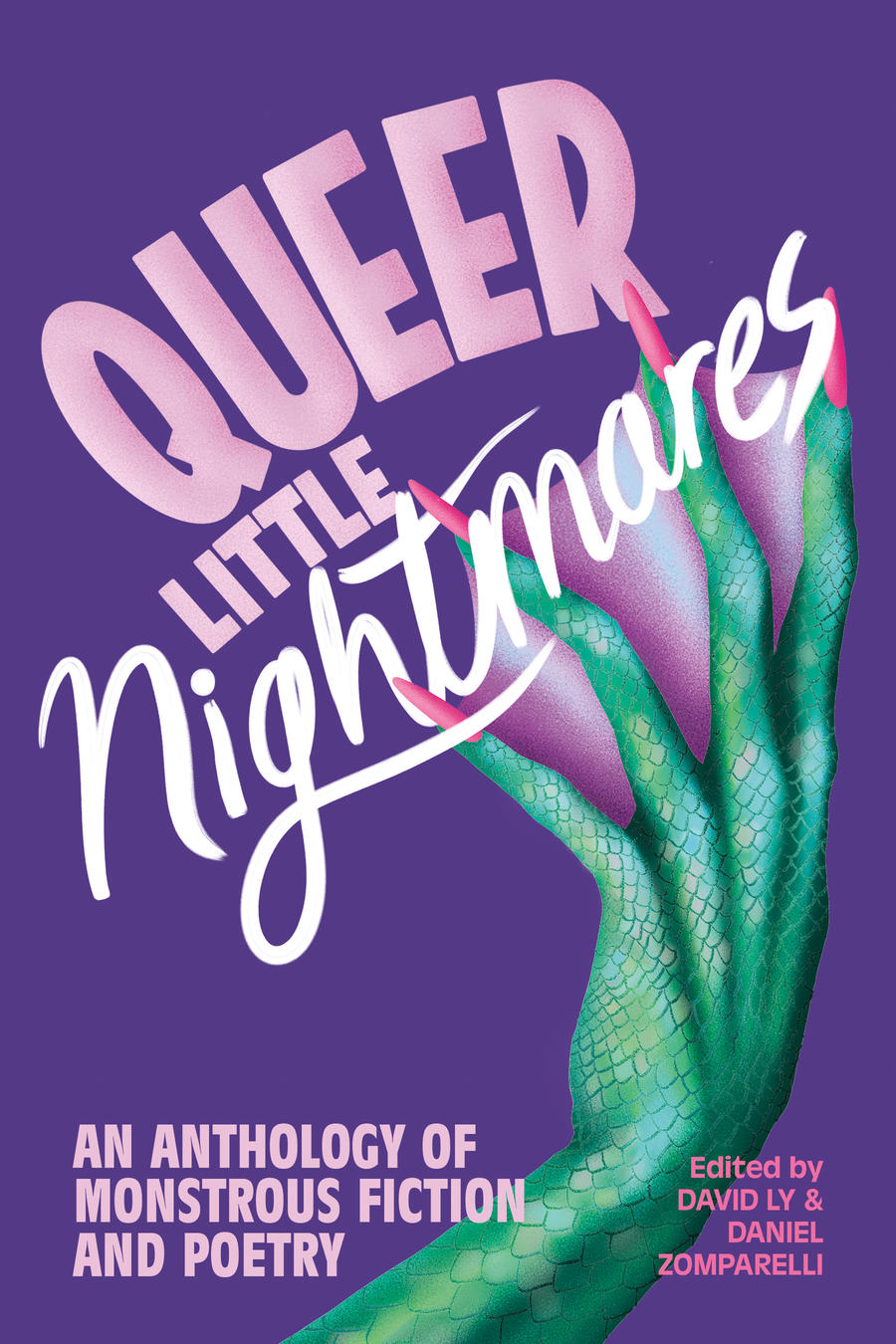

It doesn’t have to be an either/or question. Queer Little Nightmares, the new anthology of queer horror writing from Arsenal Pulp Press, out in October, makes a bouquet of compelling arguments for queer beastliness and depravity, as well as desire and connection, as imagined by queers themselves. It’s an unsettling and expansive anthology of queer horror, with a focus on monsters and monstrosity, assembling an exciting array of writers from Canada and the United States. Its collected short stories and poems push back at and play with the concept of the queer monster or freak as a pop-culture stand-in for those who are marginalized by their inability and/or unwillingness to conform. In these pieces, monstrosity is by turns flirty, heartbreaking, disgusting, humiliating, terrifying—and sometimes even freeing.

Editors David Ly and Daniel Zomparelli are seasoned writers themselves: Ly is a poet, based in Burnaby, and the author of two collections to date, Mythical Man and Dream of Me as Water, while Zomparelli is a podcaster (Can’t Lit and I’m Afraid That), poet (Davie Street Translations) and fiction writer (Everything Is Awful and You’re a Terrible Person), currently living in Los Angeles. They’ve curated a strong showing of new queer writing, both poetry and prose, from established voices like Amber Dawn (Sodom Road Exit, My Art Is Killing Me), David Demchuk (Red X, The Bone Mother), Hiromi Goto (Shadow Life, The Kappa Child) and Kai Cheng Thom (I Hope We Choose Love, Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars; Kai is also Xtra’s regular advice columnist), as well as emerging writers like Cicely Belle Blain (Burning Sugar), Eddy Boudel Tan (The Rebellious Tide, After Elias), jaye simpson (it was never going to be okay) and Victoria Mbabazi (FLIP, chapbook).

“There’s this tender emptiness inside me,” declares the teenage protagonist of Amber Dawn’s “Wooly Bully.” Later, blacking out under the thrall of her cute lesbian werewolf companion, she discovers “My VOID”—the ultimate empty space, which starts in her mind, but overtakes her physical self as well. It can be filled with all manner of things: queer lust, queer love, rebellion. In this space, she transforms. She becomes a gay werewolf herself.

A tender emptiness, a void, inhabits many of the anthology’s protagonists, whether they are already monsters, becoming monsters, or in love with monsters. In this void, bodies, lives and psyches are remade—with both wondrous and hair-raising results.

The acts and rituals of transforming queer and trans bodies are common themes across the contributions. As Amber Dawn’s protagonist finally kisses her werewolf crush, she enters a “vastness” in which her conservative rural community and its rules and expectations cease to exist, in which the two girls/monsters get to fully inhabit their bodies and desires: “In this moment, we remake ourselves. We are becoming.”

Andrew Wilmot’s “Glamour-Us” approaches the remaking of the self from a different vantage point; it thinks deeply about gendered appearances and performances, through the lens of advanced technology. In the world of this story, people can, for a high price, clone themselves, uploading their consciousness into a new synthetic body with the exact physical characteristics that they desire. Two trans characters argue about this process. One sees it as “a way to bypass the painful middle ground she’s witnessed with so many transitions,” while the other is disgusted at the idea, saying that the physical and psychological process of transitioning is an important part of the journey: “I don’t want to live in any skin that ain’t already mine,” she declares. Meanwhile, the story’s non-binary protagonist struggles with whether or not they should pay for a Glamour, an implant attached to a Dhalgren-esque hologram projector that will allow them to choose from a variety of differently gendered appearances at the touch of a button. The story explores some of the consequences and joyful possibilities of shifting appearance and identity at will.

“I was this in-between-gender boy-thing and then I was this giant woman, full of valleys and peaks.”

Jack, the protagonist of Eddy Boudel Tan’s “Strange Case,” is similarly preoccupied by how others see him, though his story is firmly rooted in the recognizable world of hospital shifts and hookup apps. He remakes himself, not by becoming a monster or a clone, but by catfishing his hot co-worker online. His fake whiteboy profile is a response to the classic racist profile text: “Please be fit, masc, and not Asian.” Taking on a new identity and appearance initially bears fruit, but it eventually leads Jack to more unsettling places within himself.

Among those receiving new or updated identities are a slew of mythological characters from a range of traditions. Familiar figures from Greek mythology are remade by both jaye simpson and Ben Rawluk. In simpson’s clever story “#WWMD?” we are left guessing who “M” is until the end. The main character, an Indigenous trans woman, lives in a world parallel to ours, one in which colonization, Instagram and the physical rituals of transition exist alongside mer-people and shape-shifting owls who may be Athena, the goddess of war. simpson gives a welcome twist to the usual reverence for Greek mythology; the protagonist declares, “They aren’t my gods.” The narrator is staunch in their own body, deemed monstrous by some: “I was this in-between-gender boy-thing and then I was this giant woman, full of valleys and peaks.” At the end of the story, despite another physical transformation (one they didn’t choose), the narrator remarks, “It’s half in ruin, but I see the potential” seemingly about a rundown warehouse they’re about to move into, though they could be referring to their new power to freeze leering men on sight, or the state of the world they live in and, by extension, our world, from a distinctly Indigenous perspective.

Ben Rawluk also subverts the familiar lines of Greek mythology by narrating from the Minotaur’s point of view in the story “The Minotaur and Theseus (And Other Bullshit).” Theseus, the hero in the Greek myth, is a glib celebrity here, an actor on the hit show The Argonauts, with his own savvy PR team, while the Minotaur, our monster, is lonely and shy, stuck at a party full of Minotaur cosplayers, unwilling to eat the human sacrifices who are sent into the Labyrinth, where he once had a youthful affair with Icarus: “Like, people expected it of him, but it wasn’t like he’d ever go through with it, and the conversation was always awkward.” The Minotaur knows the gods won’t rescue him from his plight, knows that “Monsters are supposed to escape awkward situations by dying, after all.”

“David Demchuk’s descriptions are some of the most grotesque in the collection, and the story’s ending, disgusting and transformative in the least uplifting way, had me cackling in horror and delight.”

Other mythological monsters do not die, but haunt the living. In “The Vetala’s Song,” one of the most lyrical and wrenching stories in the anthology, Anuja Varghese voices the melancholy and desire of a vetala, a spirit in Hindu mythology who repossesses corpses and inhabits charnel grounds. This vetala was once a young girl, in love with another girl, in Varanasi in 1981. Queer desire being forbidden to them, she kisses her lover publicly in a moment of passion, and is swiftly and brutally punished for it. Having become a vetala, she inhabits other bodies after killing their occupants, and awaits the return of her lover—alive or dead. Like the young werewolf lesbians in Amber Dawn’s story, the vetala knows that “in order to be together [with her lover], we would both need to become something new.” She has to pass through countless horrors to get there.

Many stories and poems in Queer Little Nightmares force the reader to face horror—often of the bodily kind. David Demchuk’s gleefully scary contribution, “Nature’s Mistake,” brings its protagonist back to the abandoned fairground of his hometown, accompanied by his reluctant boyfriend, in a bid to end his night terrors. Demchuk’s descriptions of the scenes and figures found inside the fair’s dilapidated “Crazy House” are some of the most grotesque in the collection, and the story’s ending, disgusting and transformative in the least uplifting way, had me cackling in horror and delight.

Hiromi Goto also focuses on disturbing physical description in “And the Moon Spun Round Like a Top.” Bernadette, an introverted middle-aged woman, thinks she’s undergoing perimenopause, only to find herself giving birth to sentient blood clots, who become more and more demanding: “the mass of blood looked black. It was as large as a peeled guinea pig.” When her “blood creatures” begin to wreak havoc and violence, Bernadette starts asking herself whether they are her or not—how responsible is she for what her body does? In a similarly macabre story, “In Our Own Image,” Matthew J. Trafford asks how responsible we are, not just for our actions, but for the actions of our loved ones. In a disturbing tale of queer parenting (or something like it), the narrator Marcus discovers that his loving husband has been assembling “their baby” in a Bluebeard-style room in their house. The little one is horribly fashioned out of the detritus and excretions of their shared lives, dwelling somewhere on the edge of alive and dead. Initially shocked and disgusted, Marcus finds himself having to decide whether to embrace the unsettling creation of his partner. Though it seems ludicrous at the outset, the story astutely asks what love requires of us. Is queer love always monstrous in some way, whether joyfully or nightmarishly so?

“In ‘Queer Little Nightmares,’ there are many transformative (often literally) kisses, but less sex than I had hoped for and expected.”

Levi Cain’s buoyant, hilarious “Gruesome My Love” examines queer love from a more picaresque perspective. The narrator’s girlfriend is a 30-foot tall monster with an insatiable hunger, and the way she is shunned by everyone around them leads to comically escalated self-defence. The girlfriend disembowels mean neighbours and door-busting cops alike, but the lover is undeterred, even when the girlfriend reminds them, “You should be terrified.” Love units the lovers against their adversaries—who seem to be everyone else in the world. Is the narrator naive, with a death wish, or simply protecting their relationship from bigotry and hatred? “It’s impossible to look at her and not want to give her things, whether it’s the world or a femur,” the narrator declares happily, dismissing the trail of dead bodies behind them as “people resting face-down on the street.”

Would we rather be in love with monsters than alone with ourselves? In their vampiric poem “You’re No Longer Invited,” Victoria Mbabazi writes of the cycles of loss in love: “still I am nothing/ without a haunting.” beni xiao approaches the question with some refreshing absurdity in the poem “Naga Mark Ruffalo Dream,” in which the speaker, dreaming, is introduced to “the King of Nagas,/ it’s mark ruffalo.” A naga is a half-human, half-cobra semi-divine being from various South Asian and Southeast Asian mythological traditions. “i think he/ misreads my embarrassed arousal for/ fear” admits the speaker. “i’m not scared, but turned on.”

One of the ways in which queer and trans people have been deemed monstrous by cishet society is through the sex we have, or are imagined to be having. In Queer Little Nightmares, there are many transformative (often literally) kisses, but less sex than I had hoped for and expected, especially given that this is a queer collection with a focus on monsters and bodies. Much of the horniness is found in the anthology’s poems. In Matthew Stepanic’s “Ghost’d,” a haunted condo holds the promise of ghost sex for anyone brave enough to enter and communicate via Ouija board: “If you ask politely, he will trace the/shape of his cock on the board.” In another poem, “An Invisible Man Is Humping a Vampire” by Steven Cordova, the scene described by the poem’s title occurs between two HIV-positive “AIDS-cocktail-guzzling daddies” leading to an “invisible vampire baby” who tragically shuns its parents; even the monster offspring of two HIV-positive men “fears them.” Avra Margariti’s “Cryptid Cruising” is an homage to public park cruising grounds, beyond the reach of the cops. It could just be that I’ve been reading a lot of 1990s gay literature recently (Samuel R. Delany’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Dennis Cooper’s George Miles cycle, Rabih Alameddine’s Koolaids, all of which deal in sex and nightmares), but I wanted more cruising—and actual sex scenes as well, which are mostly absent from this volume.

Nonetheless, there is much to be compelled and haunted by in this anthology. These queer nightmares hold the reader tightly, so that we feel complicit in the monstrous acts, desires and transformations. Whereas the trope of the “evil gay” is flat and without nuance, this anthology portrays queer monstrousness as a prismatic, many-headed power, not evil but not good, either. One of the joys of being queer, after all, is that of subversion, to behave “incorrectly” within and against oppressive power structures. The ultimate gift of this collection is to illuminate our own monstrous qualities and temptations, to bring us closer to what’s uncomfortable, disgusting, disobedient and vicious within us, but also to what’s exciting, ecstatic, pleasureful and liberatory.

Queer Little Nightmares editors David Ly and Daniel Zomparelli host an evening of readings, performances, prizes and games with anthology contributors jaye simpson, Amber Dawn, Eddy Boudel Tan, Tin Lorica, Ben Rawluk, Jane Shi, Cicely Belle Blain and beni xiao at 8:30 p.m. PT on Friday, October 21, as part of the Vancouver Writers Fest. Monster costumes are encouraged but optional; masks are mandatory.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra