Bertrand Mandico makes genre movies for queer audiences. His latest, After Blue (Dirty Paradise), is a lesbian sci-fi Western set on a distant planet—the titular After Blue—colonized by humans after Earth’s social, economic and environmental collapse. The story follows mother and daughter Zora (Elina Löwensohn) and Roxy (Paula Luna-Breitenfelder), aka Toxic, into exile as they chase down notorious killer Kate Bush (Agata Buzek), a character named after the 1980s chanteuse. This lurid fantasia is crazier than it even sounds, a genre-defying and gender-bending adventure that discomfits as it entertains.

After Blue, which screened at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), and gets its U.S. commercial release on June 3, is Mandico’s second feature. A graduate of the world-renowned Gobelins animation school in Paris, the writer/director transitioned to live action with 2011’s Boro in the Box, a 40-minute phantasmagorical take on the life of cult Polish filmmaker Walerian Borowczyk, who also started as an animator.

Mandico, who told Xtra he identified as pansexual, agender and xenogender “when I sleep,” weaves camp, surrealism and genre tropes into highly stylized films that blur boundaries and eschew binaries. His objects of desire attract and repulse, and he often mixes eroticism, body horror and humour in ways that force viewers to confront the damaging effects of conventional sexual norms, societal values and gender stereotypes.

His landscapes are sexualized, too. In his debut feature, 2018’s The Wild Boys (Les Garçons Sauvages), delinquent schoolboys drink the nectar of a phallic tree. This unsettling scene simultaneously reads as stylized fellatio (or suckling on a maternal teat) and begins the boys’ transformation into girls. In After Blue (Dirty Paradise), a drunken Zora is seduced and cocooned by a mineral/vegetable creature—a moving fruit-bearing tree with a geode head.

On the surface, After Blue resembles a 21st-century take on Roger Vadim’s Barbarella, but Mandico steers clear of Swinging Sixties sexploitation. He questions the dynamics of intergenerational desire and power imbalances in the psycho-sexual bond that connects the young Roxy to Kate Bush, and the attraction between her mother Zora and an artist named Sternberg. A reference to frequent Marlene Dietrich collaborator Josef von Sternberg (who helped craft the queer icon’s drag/camp persona), the painter is played by the delightfully campy Vimala Pons, whose performance skewers the art world.

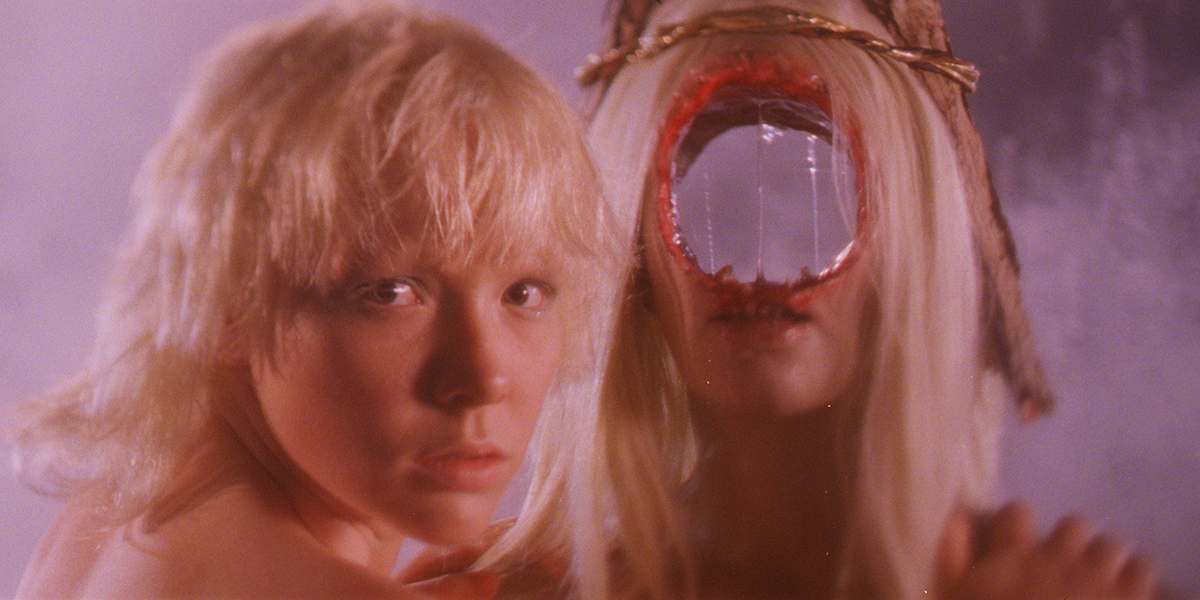

Credit: Courtesy of Ecce Films/Ha My Productions

While Mandico also pokes fun at fashion, there is little technology on the planet After Blue. The screens that isolated people from one another are gone, but guns remain and are named after fashion designers like Gucci, Chanel and Paul Smith. The one male on the planet, a sexbot named Olgar 2, played by Michaël Erpelding, is branded a Louis Vuitton, further establishing the connection between exploitation, violence and fashion. The film seems to be asking: Where do we bury our dead after we’ve poisoned the Earth? And, given the persistence of fashion labels, the art world and hairdressers: Why are we still obsessed with keeping up appearances when the apocalypse has come and gone?

Xtra interviewed Mandico by email when his film screened at TIFF last fall.

Can you talk about the origins of After Blue (Dirty Paradise)?

I started writing a queer, surrealist Western set in the United States in the late 19th century. It had an all-male cast, except Olgar-2, who was initially a woman. I set it aside for a time and returned to the text after The Wild Boys. That’s when I decided to gender-flip the characters, and the bulk of the cast became female with the one remaining male role. I did not change the characters in any other way, and this writing exercise became a way of fleshing out these parts while trying to avoid stereotypes.

The story incorporates influences ranging from the genie in One Thousand and One Nights to the reluctant heroes of The Man Who Killed Liberty Valance and Little Big Man. There is also a spiritual dimension in the notion that the world of the living can only be built by accepting the dead, an idea that references both Cocteau and pagan rites.

Your films are steeped in a gender-bending aesthetic. What is your stance within this space, beyond the traditional binary of masculine and feminine?

I stand for the abolition of gender boundaries and am a proponent of fluidity and pansexuality. I demand the freedom to be, to appear, to do and to change.

How have queer culture and cinema informed your personal and artistic development?

I was weaned on queer culture, starting with [Jean] Cocteau’s films in childhood. As a teenager, I thrilled to Querelle, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s cinematic take on novelist Jean Genet. Next, I discovered the arcane films of Kenneth Anger and John Waters’s underground insanity. My visual education was a string of subversive, experimental queer films by the likes of John Bidgood, Werner Schroeter, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Shuji Terayama and Sergei Parajanov.

I later discovered Genet’s Un chant d’amour [the novelist’s only film], a pillar of my cinematic education and one of my favourite films to this day.

These films magnify and stylize reality, embracing the eroticism and urges that drive their characters to the margins of society. Fellini took up their queer aesthetic in Satyricon and Toby Dammit. When I saw these two seminal films, I was young and sick with fever and felt like I was dreaming and living inside them. This constellation of films and filmmakers guided and shaped me. My imagination is steeped in their images that continue to brew in my head like a fragrant tea.

Your most frequent collaborator is the Romanian actress Elina Löwensohn (Zora in After Blue), who often co-writes your films. Is your partnership a response to the often exploitative and unequal relationship between artists and their so-called muses?

I don’t like how the word “muse” is used or perceived. The image of the active artist and the passive muse is at once backward and one-sided. I see working with Elina as an ongoing conversation. Ours is an inspiring and inspired collaboration. We play at filmmaker and actress, questioning the dynamic of these overused tropes. The goal is to give Elina the freedom to play unconventional characters, who are fully realized, without boundaries and at once glam and anti-glam. I feel that Elina and I are holding up funhouse mirrors to each other and playing with our distorted reflections.

What impact have comics had on your work?

Comic books, particularly Métal Hurlant (Heavy Metal), played an enormous role in my childhood imagination. I used to buy adult comic magazines on the sly because I was officially too young to read them. They were the ultimate drug, and a visual shock to my system. The illustrations in Heavy Metal plunged me into parallel worlds and alternate universes and gave me a taste for unbridled narratives, baroque subversiveness and manufactured realities completely disconnected from my own.

As a filmmaker, I have grafted together multiple sources, including cinema, comics, novels and records, to build my mutant imagination.

Like Stanley Kubrick, you rework the popular genres of your youth by making science fiction, fantasy, Western and adventure films. Can you please elaborate on this process?

I think it’s a shame that auteur cinema too often abandons popular genres, leaving them in the hands of the big studios. There are, of course, financial considerations. Can you find inventive ways to overcome your limited budget? While the substance of an auteur film is its core, you can play with its form and invite the viewer to join you in a liberating game, especially when you’re reinventing a genre. I like to have fun revisiting and remixing genres and take great pride in my flair for overcoming my limited funding.

Are your films a reaction to franchises like the Marvel Cinematic Universe?

After Blue (Dirty Paradise) is part of a trilogy that started with The Wild Boys and will conclude with my gender-flipped She is Barbarian, dreaming of a character that Robert E. Howard might have invented. However, it is true that, while filming After Blue, I wanted to spend more time on this alien planet and use it as a setting for other stories. I feel like a spider weaving a massive web that connects all my work. My experimental and short films, features and music videos exist in a shared universe. They intersect and form an extended running commentary on one another.

My answer to Marvel movies is that fantasy belongs to the imagination and not the film industry. Fantasy is all about perspective. You must know when to hint at something instead of revealing it. Showing everything is a form of cinematic exhibitionism and a love killer. I have been forced by financial constraints to cultivate mystery by balancing modest effects against outrageous ideas.

The opening of After Blue describes the virus that killed off the planet’s male population as sparing “carriers of ovaries.” Some viewers may see this as a reductive view of women that is trans-exclusive. Others have also claimed that your debut film, The Wild Boys, depicts biological determinism. As a queer artist who rejects gender binaries, how do you react to such criticisms?

In arbitrarily creating a virus that only attacks those born male, I created a lopsided universe that forced me to limit the types of characters I could represent. This does not make it an ideal world. On the contrary, I am depicting an unbalanced and amputated world. The restrictive setting of After Blue is a conceit that allowed me to create a stylized universe offering women actors unconventional roles. In fact, one of the cast members is the non-binary artist Franky Gogo, who plays one of the leading villagers in the film.

Biological determinism is an abhorrent concept that turns my stomach. I believe in free will and feel that misinterpretations of The Wild Boys are grounded in mischaracterizations of what I’ve been saying, which I find distressing and extremely depressing. These subjects inflame passions and spark demands, and rightfully so. But we must not mistake the enemy. Instead, we should align against the vast number of films that ignore these questions entirely.

The Wild Boys generated a lot of excitement in the trans and queer communities, but I must accept that my fantasy writing does not appeal to everybody. Also, fiction uses narrative devices that should not be mistaken for theoretical discussions. To tell you the truth, although I don’t like to reveal the details of works in progress, I am working on a new film in which the main characters are trans folk played by trans actors.

This interview has been translated from French and edited for length and clarity.

Clarification: June 2, 2022 4:22 pmThe title and description of the third piece in Bertrand Mandico’s proposed trilogy has been updated since this story was first published.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra