Jenny and Tara were already dead when I lost Shay. I’m not sure why hers was the death that hurt the most. Maybe it was that I’d never really liked Jenny to begin with (and who had?). Maybe it was that I was too young to fully understand the devastating loss of Tara. Maybe it was that, in Shay, I saw someone a bit more like me: someone who certainly didn’t have it all together, but who was trying, who was surrounding herself with a circle of friends, an urban family of support and laughter. Losing Shay didn’t just make me sad; it made me angry.

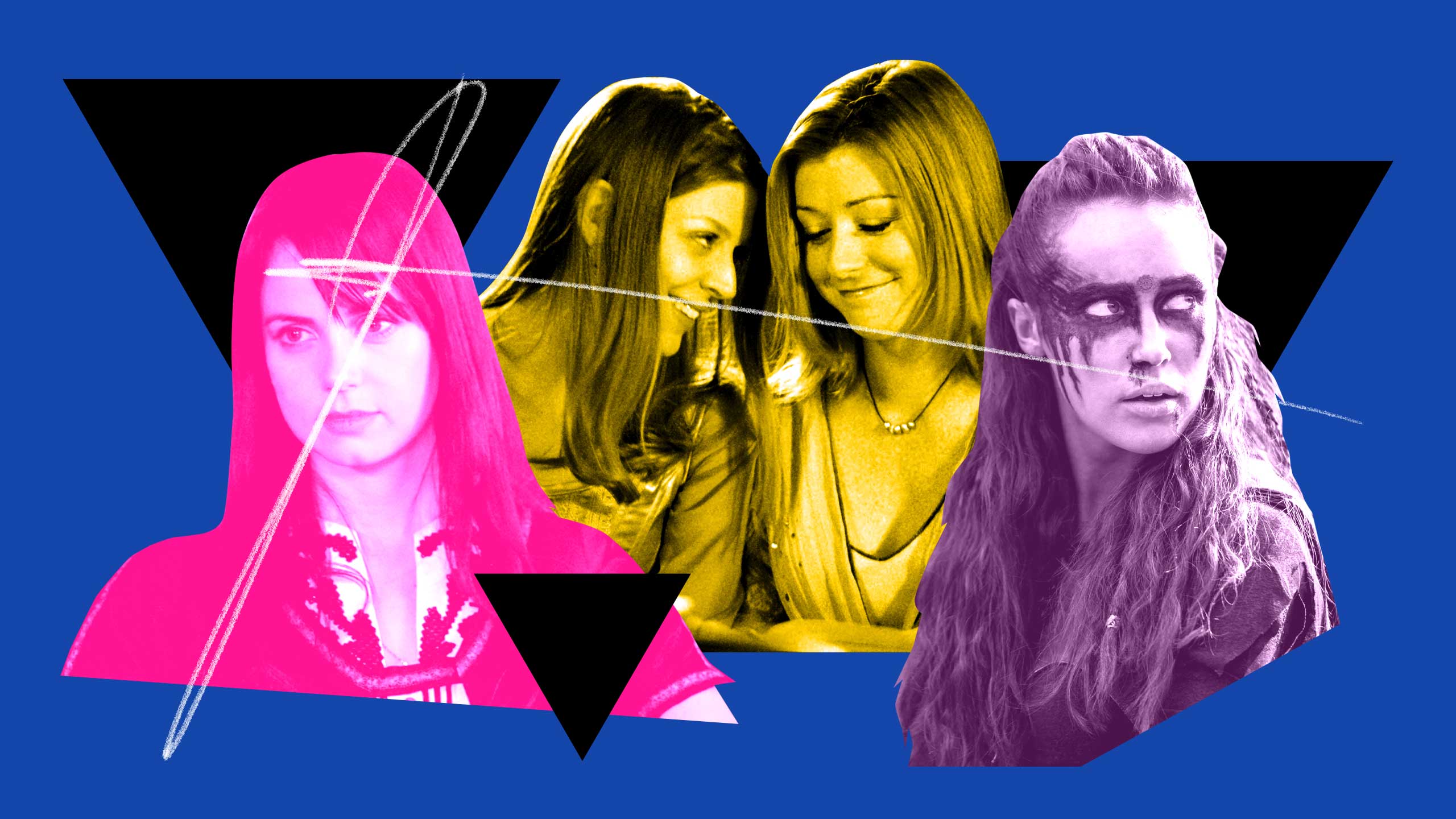

Jenny Schecter (The L Word), Tara Maclay (Buffy the Vampire Slayer) and Leslie Shay (Chicago Fire) are just three of countless fictional women to suffer death by trope. The latter—known as Shay to her friends—was the spunky, confident lesbian who, despite her penchant for shacking up with the wrong person and over-reliance on tequila, proved to be a reliable, loyal friend in her short-lived stint on the primetime drama Chicago Fire. She was my favourite character; watching her perish in a devastating conflagration wasn’t just a massive disappointment, it felt like lazy writing. Shay’s death was above all a wrench in the works, a plot point that gave straight characters something to grapple with. The blow of that—of queer representation as fodder for the straights—is exhausting at best and devastating at worst. In fact, the trope is so overdone it has its own name: Bury Your Gays. And while we’ve taken strides in recent years to eradicate it, the work is far from over.

Haley Hulan, a graduate teaching assistant in Northern Michigan University’s English department, notes in their 2017 research paper that the Bury Your Gays trope dates so far back it precedes the invention of television, appearing as early as the 19th century in works like Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Generally, they write, the trope sees “one of the lovers dying and the other realizing they were never actually gay, often running into the arms of a heterosexual partner.” Raina Deerwater, an entertainment research and analysis manager with LGBTQ2S+ media watchdog GLAAD, echoes this, noting that the 1930 Hays Code, which established “moral guidelines” for films, led queer-coded characters to be “categorized as ‘immoral.’ [They] had to be somehow punished by the end of the story, which often resulted in them being killed off.”

And while for Hulan the trope actually got its start as a resource for queer creators (Wilde among them) that allowed people to write about gay characters without being criticized for “endorsing” homosexuality, Bury Your Gays has far outlasted its original purpose. “Bury Your Gays persists today in a time and social context in which it is no longer necessary to give gay characters and stories bad endings in order to be published,” writes Hulan.

Today, the trope is overwhelmingly used exploitatively. In some cases, it’s to propel the narratives of straight characters: in Chicago Fire, Shay’s death was used mainly to pave the way for a despondent Kelly Severide (played by Taylor Kinney) to mourn her for much of the next season. Or, Hulan notes, the trope is used “for the perceived shock value that queerness’s depiction can have for straight audiences.” One of its most notable television uses (and the one that got it nicknamed “Dead Lesbian Syndrome”): Executive Suite’s 1976 decision to send lesbian Julie into the street in pursuit of her love interest, only to be immediately run over by a truck. (Yes, it’s ridiculous. And it also happened again—in equally ridiculous nature—on the British lesbian drama Lip Service in 2012.)

The overwhelming deadliness of being an onscreen lesbian, Hulan says, is due in part to the fact that women-loving-women (WLW) couples get more screen time than men-loving-men (MLM) couples. “Lesbians are sexualized in our culture,” Hulan says, “making exploitative storylines about them more abundant, and the presumed-male audience of action-oriented movies and TV (of which there is currently an abundance) finds WLW couples more approachable than MLM couples.”

And since queer characters are still most often found, Deerwater asserts, “in smaller ensemble roles rather than as series leads, this makes them more easily dispensable when writers are looking for shock value or series cuts.”

The trope seemed to come to a head in 2016 and 2017, when Jane the Virgin’s Rose, The Magicians’ Kira, and The Walking Dead’s Denise all died within 30 days of The 100’s Lexa, as Dorothy Snarker noted in the Hollywood Reporter. To add insult to injury, the latter was killed mere minutes after consummating her much-awaited and teased relationship with lead character Clarke. The death caused such an uproar among fans that some banded together to pen the “Lexa Pledge,” asking writers to commit to “refuse to kill a queer character solely to further the plot of a straight one.” (Some agreed; many did not, citing artistic freedom and poetic license.) Pink News reported in 2017 that 62 lesbian and bisexual characters had been killed off in the two years prior, and according to an Autostraddle infographic made in 2016, only 8 percent of queer female characters on TV got a happy ending.

If the titles of the first six episodes of ANNE+ are any indication, Dutch collegiate Anne is defined first and foremost in terms of her relationships with other women: Anne and Lily; Anne and Sara; and Anne and Janna. But the series is so much more than that. The titular Anne is navigating the world of love and heartbreak, but she’s also a passionate reader and writer, a loyal friend, a loving daughter, a creative storyteller, a fan of a big night out in her adopted city of Amsterdam. As her time at university comes to an end, she has reached an impasse—and it has nothing to do with her sexuality. Queerness is a piece of the tapestry of who Anne is: sometimes, as when she dates the not-quite-out-yet Sara or helps friends stage a queer-positive protest, it’s more at the forefront; other times, as when she is struggling with her career and the direction of her creative pursuits or grappling with her parents’ divorce, it takes a backseat.

“It’s sad that so many queer movies/series are about sad queer people who struggle with their sexuality or they just die,” says Maud Wiemeijer, the Dutch writer behind the series. She and her co-creators, on the contrary, “wanted to make ANNE+ light and happy. Positive representation is so important. We want to show that you can be queer and happy.”

It’s exactly the kind of representation Wiemeijer says she looked for a young queer person—often in vain. “Skins UK meant a lot to me, even though it also had a lot of drama,” she recalls. Over the course of its six-season run, Skins followed three different groups of sex- and drug-focused Bristol teens for two years at a time; it spent much of seasons three and four focused in part on the will-they-won’t-they relationship between confident, pretty much out Emily and in-denial Naomi. (In Season 7, Naomi dies of cancer.)

“In 2016, only 8 percent of queer female characters on TV got a happy ending.”

Despite once more fulfilling that too-tired trope, Skins, as far as Wiemeijer is concerned, offered essential representation. “It was about girls my age and I really appreciated that,” she says. “It was just very relatable and realistic.”

“The L Word was good,” she adds. The L Word, of course, killed off both Jenny and, in far more heart-wrenching fashion, fan-favourite Dana—the former in a mysterious drowning that propelled much of the let’s-not-talk-about-it sixth season, the latter of cancer. “But it was about all these successful attractive lesbians in their 30s in L.A. As a 14-year-old Dutch girl, that felt lightyears away.”

In making ANNE+, Wiemeijer says, she sought to create “the content we missed when we were young. A show about young happy queer people our age.”

And it’s resonating with viewers. Not only did Orange is the New Black’s Laura Gomez take on a guest role in the second season of ANNE+, but the team recently released a feature film based on the show, which is now available on Netflix.

Canada’s Sarah Rotella leaned into the same impulse of showing the happy side of queer life when, beginning in 2012, she started making comedy shorts for the Gay Women Channel on Youtube. This inclination is also apparent in the feature films she has since produced with writer Adrianna DiLonardo.

“On my first date ever with a girl in high school, we watched Lost and Delirious, which included the lesbian characters being outed, going back to boys and jumping off a roof. Yikes,” Rotella recalls. “Looking back on the LGBTQ+ films I watched as a young lesbian, I wanted to see characters reflect my experience, but I could never relate to what they were going through. It mostly instilled the stereotype that people would react negatively to my coming out.”

Her Youtube channel looks to the lighter side of queer life, “to talk about the fun side of being of lesbian.

“Our early content would poke fun at stereotypes, make fun of past experiences, and feature us being out, loud and proud,” Rotella says. In the regular “Pillow Talk Monday” series, for example, Rotella and DiLonardo rate sex scenes in lesbian movies or list “things lesbians hate,” which often either play into or confront stereotypes head-on in a way that feels fresh and honest. Scripted sketches, meanwhile, feature beloved characters like the mesmerizingly monotone “Gay Aunt Barbara” (played by Hannah Hogan) or DiLonardo’s lesbian cooking show host, whose emotional range rockets from despondent to heartbroken to just plain pissed. Rotella and DiLonardo teamed up with some of the crew from BuzzFeed for a lesbian spoof of Queer Eye, and in 2012, they produced a sketch called “Gay Women Will Marry Your Boyfriends” in response to the push for gay marriage legislation. (The skit featured lesbians pledging to conquer the hearts of straight men through their unlimited access to hockey tickets, adeptness at yoga and love of video games.)

“Sometimes lesbians just want to throw on a funny movie, too.”

“We’ve heard from so many baby dykes who have watched our channel over the years that we helped them come out just by showing being gay is fun,” says Rotella—which, she adds, is what she is looking for in more mainstream content as well. “Sometimes,” she says, “lesbians just want to throw on a funny movie, too.”

This is perhaps why Happiest Season—a cheesy holiday film featuring Kristen Stewart and Mackenzie Davis—was so highly anticipated last Christmas, and why for many (including Wiemeijer) it fell short. After all, while all three lesbian characters survive the film, its main dramatic focus centres, if not on death, then on a deep-seated fear that being who you are is somehow wrong—the very notion that led many queer creators to start relying on the Bury Your Gays trope in the first place.

“I was quite disappointed,” says Wiemeijer. “Why give the main character such a toxic family and relationship? Once again, being gay was the only dramatic storyline. We deserve a lesbian romcom, but not this one,” she says. “Though I’m glad that there was room to make such a film! And it’s great that it was directed by a (queer) woman. But maybe that’s why I had expected a bit better.”

While there’s perhaps nothing more pressing on the queer lady agenda than for our WLW characters to survive, it’s important we not allow the needle to be yanked too far in the other direction. Lexa Pledge aside, a generation of impervious, immortal onscreen lesbians does not interesting content make.

Hulan cites Clark’s model of “Evolutionary Stages of Minorities in Mass Media” as an important tool for navigating the future of queer representation and for eradicating this and other tired tropes. The model, used often in scholarly circles, offers a pattern by which the representation of minority groups in media will progress, from what it calls “non-recognition” (total lack of representation) to “ridicule” (home to the bury your gays trope) to “regulation” (the sanitized representation of the gay best friend, for example). It is here, according to Hulan, that queer representation has been hanging out for the past decade, and it is up to us as audience members to hold creators accountable in order to finally move into the final phase: respect.

This means creating stories where a character being gay is not their sole defining characteristic; stories where gay characters are fully-fledged people with conflicts unrelated to their queerness.

“In ANNE+, Anne is a lesbian, but she struggles with all these universal things like heartbreak, career, friends, housing,” Wiemeijer says. “It’s not all about her being a lesbian.”

In fact, (and this is the clincher) stop making “because they’re gay” a reason to do anything at all. Letting onscreen queer characters make friends, drink coffee, deal with family drama, love, loss, an impending army of weevils or aliens, an evil sorcerer or a magical curse just exist opens up a whole new world for satisfying storylines. Booksmart’s Amy, Dickinson’s Emily, or Atypical’s Casey all have their own, fully-fledged stories where their queerness is embraced and their struggles are linked to other parts of who they are: Emily grapples with her love of Sue but also with her love of writing and fear of publishing; Amy deals just with her crush on Ryan but also the unhealthiness of having a controlling best friend; Casey reckons with her queer identity but also with her passion for running and with finding her place in a family dealing with infidelity and the needs of her autistic brother.

“If it’s only queer people who are dying, something is very wrong.”

“I’d love to see thrillers, dramas, musicals with queer people in the leading role,” suggests Wiemeijer.

Another solution? “Have more than one,” Hulan says.

“When there is only one queer character in a given piece of media, all the hopes and dreams of the queer audience are riding on that one character,” they say. “It also means that that one character is representing all of queerness and so it can feel really gross if they fall into certain stereotypes.”

Once we are firmly in the space of “respect” on the Clark scale, gay characters, Hulan says, will be able to die onscreen—and moreover, they “can and should die” if their storyline demands it.

“I mean sure, sometimes characters die because it fits the story,” Wiemeijer says. “But if it’s only queer people who are dying, something is very wrong.”

“Just like lesbian period dramas, we need some balance,” adds Rotella. “I also don’t want to know that the lesbian characters will never die. Let’s just not kill them for shock value or for no reason at all. I mean, if someone does a remake called ‘Kill Jill,’ I’d be into it.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra