Across Africa, queer people face oppression, discrimination and violence for their identities. A 2020 report by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) reveals that the continent accounts for almost half of the 69 countries where homosexuality is criminalized. State actors like the police have used anti-gay laws as pretext to continue to harass and extort money from anyone they believe to be part of the LGBTQ+ community—especially in Nigeria, where the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill stipulates a 14-year sentence for those who engage in sex with persons of the same gender. Arbitrary and discriminatory arrests of anyone perceived to be queer has become rampant across African countries.

It would be impossible to detail all the accounts of oppression queer people in Africa have faced in a single article. Instead, here are five recent events of hostility and violence in African countries where homosexuality is outlawed—and how, in spite of continued oppression, queer folks have stayed resilient.

Uganda

Police crackdowns on LGBTQ+ people have become a constant in the East African country. Since 2019, there have been four raids on Uganda’s queer community, which have resulted in a number of arrests. The latest took place in May at the Happy Family Youth shelter in Kampala, the country’s capital city. Although all 44 persons arrested were released a month later, many faced torture while in jail, which included forced anal examination to allegedly determine their sexual orientation.

Ugandan authorities have continued to use COVID-19 restrictions to specifically target the LGBTQ+ community. The case of the 44 arrested is similar to the raid on the LGBTQ+ community group Children of the Sun Foundation (COSF) last year, whose account of the event offers a glimpse into the horrible conditions queer people in Africa face during unlawful arrests and detention.

On the morning of Mar. 29, 2020, Henry Mukiibi, the founder and director of Children of the Sun Foundation, was home with his boyfriend and kids when he got a call that the organization’s office had been raided. The office, located in Kyengera, a town just outside Kampala, doubles as a shelter for displaced LGBTQ+ people. Mukiibi rushed to the centre only to be arrested as well. Those arrested were paraded from the shelter to the police station while being subjected to homophobic taunts by the surrounding community. “The mayor ordered ropes and they tied us like slaves,” Mukiibi says, tearing up over a Zoom call. “It was a shameful walk. Because people were throwing stones at us, spitting on us and boxing us.”

The police used the COVID-19 restrictions imposed the night before to justify the arrest of queer people at the shelter, accusing them of not physically distancing and formally charging them with “a negligent act likely to spread infection of disease” and “a disobedience of lawful orders” contrary to Sections 171 and 117 of the Penal Code, respectively.

Two days later, 20 out of the 23 people arrested were arraigned before the Magistrate Court and remanded to Kabasanda Prison in the district of Mpigi. In prison, they were tortured and mistreated by other inmates, and were denied food and access to the washrooms. Mukiibi recounts an experience where a prison officer ordered the other inmates to beat the group.

“It was a shameful walk. People were throwing stones at us, spitting on us and boxing us.”

But the efforts of their legal team, the Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Forum (HRAPF), saw to it that their case was dismissed. They were released after 50 days in detention. HPRAF’s fight for justice did not end there. HPRAF and COSF sued the attorney general and the commissioner general of prisons for denying the accused access to lawyers. The high court of Uganda awarded damages to the tune of UGX 5,000,000 (about $1,735) to each of the accused persons on June 5, 2020.

On the anniversary of their arrest and detainment this year, COSF commemorated the harrowing experience with an event called The Scars We Carry. (Mukiibi plans to make it a yearly event where they remember the persecution they endured and celebrate their resilience.)

But COSF still needs support. The landlord of the shelter has asked that they move due to the controversy surrounding their arrests. COSF is now seeking financial support from the international LGBTQ+ community to help continue to cater to the queer refugees and provide them health services and support.

Even though they are no longer in prison, they still suffer from the trauma of the horrible conditions they were subjected to, Mukiibi tells Xtra. Yiga Kareem, one of the two trans women who were forcefully stripped and torched with burning firewood in prison, was recently found dead in her home. The Ugandan queer community is in dire need of support as they grieve one of their own.

Cameroon

Shakiro and Patricia, two trans women living in the central African country of Cameroon, were arrested and sentenced this April for “attempted homosexuality.” The couple was at a restaurant in the capital of Douala, when they were accosted by the police and arrested for wearing women’s clothes.

While in custody, they were put in overcrowded cells with cisgender men and had to endure transphobic abuse that was both physical and verbal. Working For Our Wellbeing (WFOW), a Cameroonian LGBTQ+ organization, sprung into action, providing Shakiro and Patricia with legal aid. During their time in prison, WFOW also provided them with better food and medical provisions, and after a few weeks, the organization made arrangements to have the women moved to a better cell.

The pre-trial detention was a lengthy one, with multiple court hearings being postponed. Finally, on May 11, the judge issued a sentence: in addition to trumped-up homosexuality charges, the women were found guilty of public indecency, as well as failing to have their ID cards. They were sentenced to jail and were fined 200,000 CFA (approximately $440).

WFOW did not relent in the fight. Together with the Shakrio’s and Patricia’s attorneys Alice Nkom and Tamfu Richard, who provided their services pro-bono, the organization is appealing the case. In July, with the appeal case still pending, a judge ordered the release of Shakiro and Patricia.

WFOW’s activism does not end with Shakiro and Patricia. Nkwain Hamlet, the organization’s director, says their goals include making sure that Cameroon’s anti-LGBTQ+ laws are repealed. “We are working with other organizations to lobby at the national assembly to better commit to LGBTIQ equality and human rights,” he says. In the meantime, the organization is actively working with judicial authorities to reduce the level of arbitrary arrests, detentions and convictions of queer people.

Kenya

Wanuri Kahiu’s 2018 film Rafiki tells the story of two women in love and the obstacles their relationship faces in Kenya, where homosexuality is taboo. The film is a mostly lighthearted depiction of two women’s love for one another, but Kahiu does not fail to capture the valid experiences of queer people in their communities, where they face bullying and abuse. The film is critically acclaimed and film festival-vetted—it is the first Kenyan film to show at the Cannes Film Festival. But the country’s censors, the Kenyan Film Classification Board (KFCB), banned it from screening in Kenyan cinemas. The legal battle to overturn this ruling is still ongoing; however, in April 2020, a Kenyan court upheld the ban. Speaking to Reuters after the court’s ruling, Kahiu said: “We are disappointed of course. But I strongly believe in the constitution and we are not going to give up.”

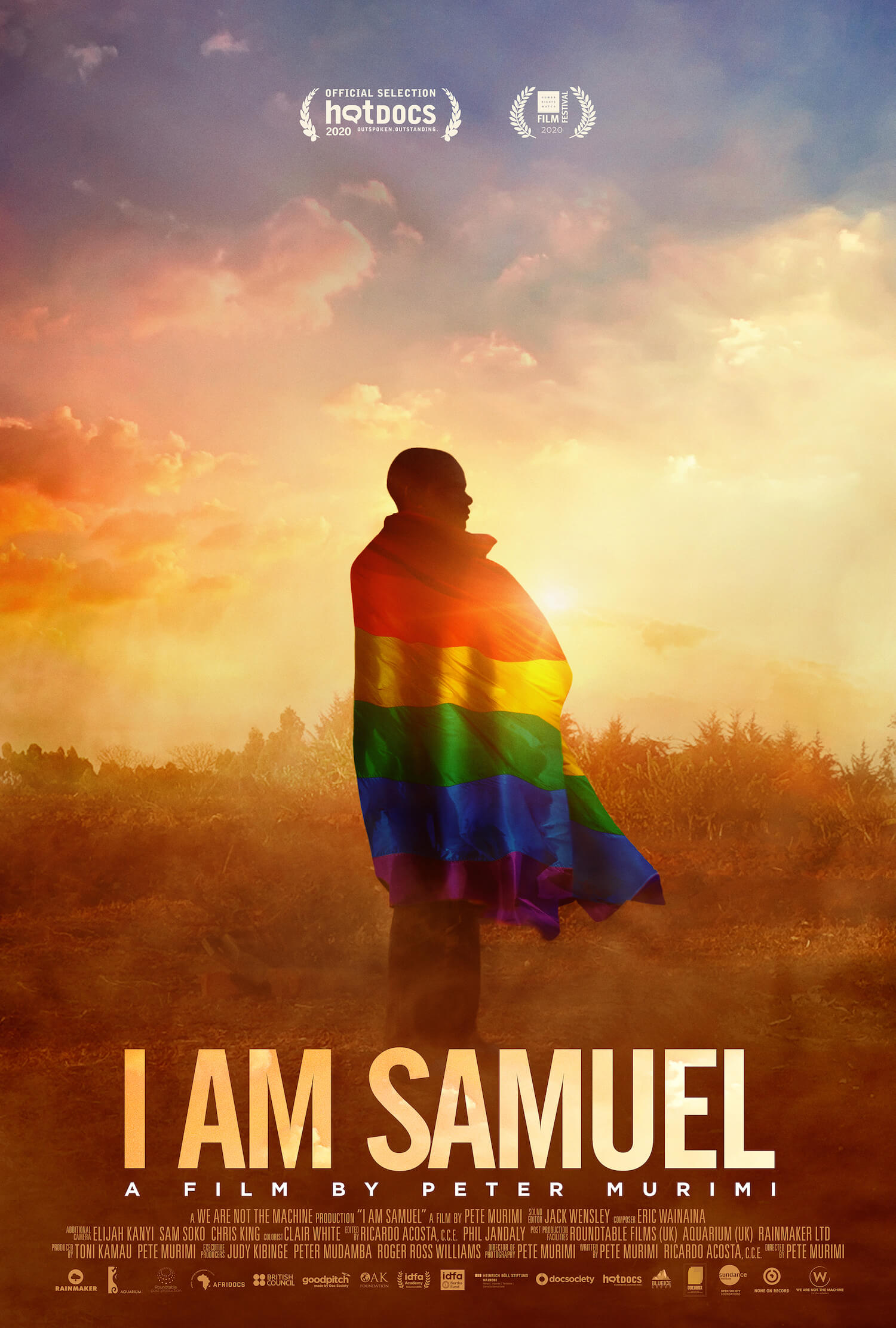

Credit: Courtesy of We Are Not The Machine

I Am Samuel, a 2020 documentary about a Kenyan man’s experiences of being queer in the African country, has suffered a similar fate. The film was directed by Peter Murimi and follows the titular character’s move from the countryside to Nairobi, where he finds love and kinship within the city’s queer community. Just like Rafiki, it was banned for its positive depiction of same-sex relationships, which the KFCB argues is against Article 165 of the Penal Code, the section that punishes acts of homosexuality with a five to 14-year jail sentence.

But unlike Rafiki, the regulatory board’s attempt to censor I Am Samuel has failed. Although they may have restricted it from a theatrical release in the country, the documentary is available to be streamed for free on AfriDocs, a streaming platform for documentaries.

Ghana

In the West African country of Ghana, the government and mainstream press have banded together against the LGBTQ+ community. Just a week after LGBT+ Rights Ghana celebrated the opening of its new community centre, it was attacked.

Abdul-wadud Mohammed, the organization’s communications director, says the community centre was created to provide queer Ghanaians with a safe space. It was also meant to serve as a social and recreational centre for the country’s queer community. But those efforts have been foiled by the government.

“We were forced to stay out of the place and go into hiding.”

In January, the organization hosted an opening event with the Australian high commissioner and European diplomats, who had come to show support in attendance. Their presence attracted media attention. The unintended consequence? Religious and political groups began a campaign against the organization, demanding that the community centre be shut down and that the activists behind its creation be arrested. Their wish came to pass after the police raided the centre and destroyed some of its belongings.

“We were forced to stay out of the place and go into hiding,” Mohammed says, noting that the organization has had to move their activities and activism online.

Currently, there’s an anti-LGBTQ+ bill in Ghanaian parliament awaiting the president’s approval. The bill criminalizes not just same-sex marriage and pro-LGBTQ+ organizations but the mere expression of support for queer people. It finds these acts a crime punishable for up to 14 years in prison.

LGBT+ Rights Ghana remains undeterred and has co-ordinated with other local and international human rights groups to oppose the bill. “We are working against the bill through the SpartaGH project, which we launched specifically to fight it,” Mohammed says. The initiative’s aim is to unite voices who oppose the bill and pressure parliament into discarding it.

Nigeria

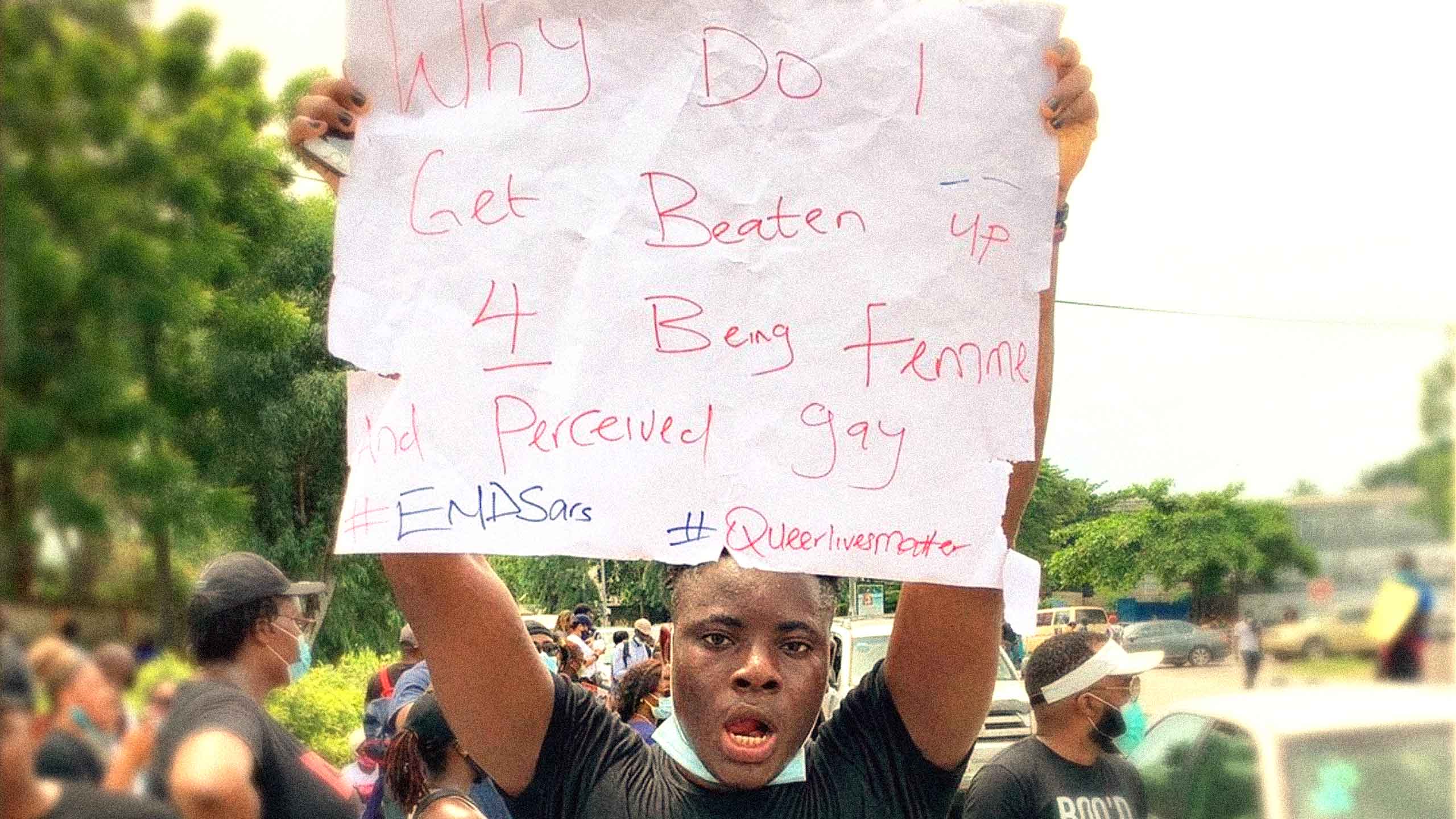

In October 2020, a defiant move by non-binary and gay activist Matthew Blaise in Nigeria motivated other LGBTQ+ Nigerians to not just join in protests but also to share their experiences of abuse from the country’s rogue police unit. During a policing protest dubbed #EndSARS, Blaise walked the streets of Lagos chanting “queer lives matter” at the top of their voice.

Although Blaise’s demonstration attracted only stares from onlookers, other queer people in the different protest sites across Nigeria were met with hostility. They were accused of trying to reclaim the anti-policing protest as a cause for LGBTQ+ rights. Queer Nigerians faced homophobic abuse and were asked to leave the protest grounds. But they persisted, insisting that they were especially targeted by the police for being gender nonconforming.

Through publicly donated funds, Blaise provided food and security for queer people protesting in different cities in Nigeria.

Blaise’s activism did not end there. They started the OASIS Project, a non-profit with set goals that include creating a positive representation of LGBTQ+ persons in Nigeria through blogging, Instagram posts and documentaries to counter the negative stories about queer people pervading traditional media.

Their work also includes physical events that serve as a safe space for queer people to have healthy conversations around mental and sexual health. Blaise plans to organize workshops and panel eventsvin the future; they also they want to open shelters for displaced and ostracized gay and trans folks in Nigeria.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra