The Slumber Party Massacre kicks off with a salacious bait-and-switch. We learn through a radio broadcast that Russ Thorn, a deranged serial killer, has escaped from prison and is on the loose. Trish Deveraux, a girl who will ostensibly be our protagonist for the ensuing 75 minutes of guts and sex, is listening to the radio as she gets ready for school. Within two minutes, Trish is bare-chested, her breasts on screen for no apparent reason.

As she heads to school, we learn that Trish’s parents are going out of town—she’ll be home alone! At school, unbeknownst to Trish, a couple of hapless teen girls are violently murdered by Thorn, who is wielding a thick and impossibly long power drill. We’re also treated to several sex-drenched sequences: the first is a basketball game, where the girls jump around in the shortest shorts I’ve ever seen; the second, an extended shower sequence where all the girls are butt naked and wet. This all happens in the first 15 minutes of the movie. If it were 1982 and you were a hormonal tween boy looking for hot naked girls and gnarly violence, then The Slumber Party Massacre would have seemed like the movie for you.

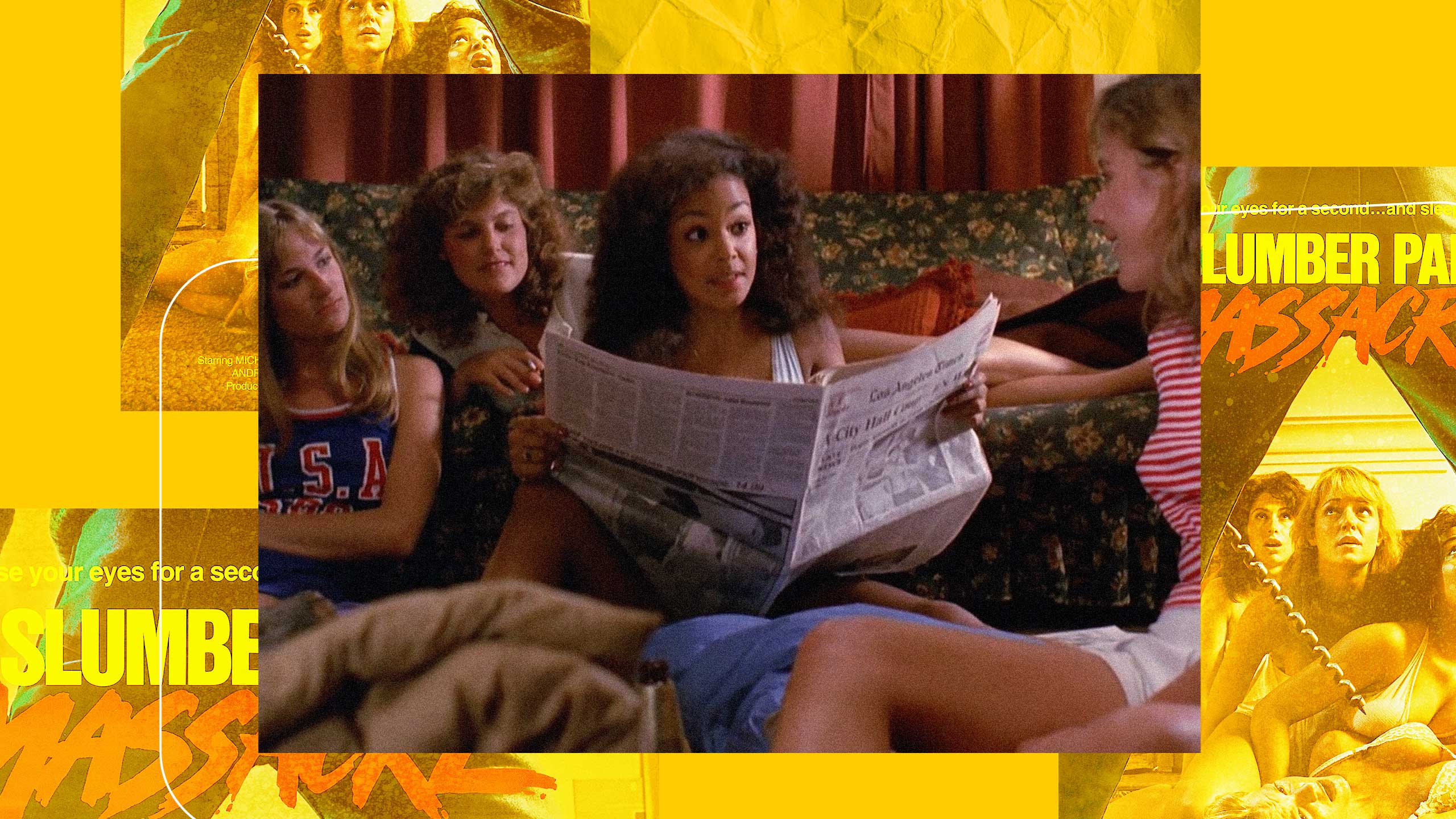

But after the movie’s first truly great kill—a blood-pumping, action-packed cat-and-mouse chase through a locker room—something strange happens. The movie’s clipping pace steadies, and it morphs into something else entirely. The murder and sex largely subside as we watch the group of friends who make up the titular slumber party go about their lives for most of the movie’s remaining runtime. They hang out with each other, making plans for the slumber party and bump into their boyfriends, all blithely unaware of the massacre that awaits them.

It’s an odd subversion of horror tropes that’s notable in 2021, but it would have been shocking when it came out. The Slumber Party Massacre was released in 1982, a short four years after John Carpenter’s Halloween came along and established the slasher tropes that remained largely intact during the genre’s imperial era in the early ’80s. Your typical slasher goes as follows: a big, splashy kill sets the stakes and whets the viewer’s appetites; the teen victims are introduced and get into some debauched, sinful antics; they’re killed one by one in increasingly creative ways by our big scary killer, who is usually wielding some household tool refashioned into a deadly weapon; after realizing her friends are dropping like flies, our virginal Final Girl encounters the killer and is chased around, only to defeat but not kill him in the end. Women in these movies were generally considered bodies to be gawked at and torn apart for the pleasure of the film’s (largely male) audiences. Movies like Friday the 13th and Prom Night, both of which came out in 1980, made millions by drawing on Halloween’s influence, and cemented the slasher as a cheap, easy way to make formulaic films with built-in audiences.

“The film is a testament to how queer brilliance and proper fun don’t have to be mutually exclusive.”

This formula would have been drilled into the kinds of people going to see a movie called The Slumber Party Massacre by its release in 1982. It’s with that context that I invite you to relish in how deliciously subversive this movie is; it’s a testament to how queer brilliance and proper fun don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

It all began when Rita Mae Brown, author of the lesbian classic Ruby Fruit Jungle, wrote a screenplay called Sleepless Nights. At that point in her career, Brown was a well-established feminist activist and author, one who fought tirelessly for the inclusion of queer women as the movement flourished in the 1970s. She was the kind of gadfly that moved our community forward in ways that reverberate to this day, and her legacy tends to be a serious one. Sleepless Nights, a madcap feminist parody of slasher movies written in the genre’s infancy, isn’t exactly the kind of thing you might expect from a person like Brown.

But Brown, ever the radical, was perhaps a bit too ahead of her time. The screenplay she wrote was much more Scary Movie than Scream, and when she submitted it to producers for edits, they pared back the comedy and left the scary bits, hoping to make it more commercial. It was renamed Don’t Open the Door with Amy Holden Jones, a film editor desperate to transition into directing, as its director. Jones shot the first three scenes of the new screenplay and somehow got an audience with Roger Corman, a horror legend who’s produced hundreds of B-movies and has helped launch the careers of folks like Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese. Corman, impressed with Jones’ work, agreed to finance the film, and asked Jones to continue directing. She turned down a gig editing E.T. and got to work on what would eventually become The Slumber Party Massacre.

Horror has always been a genre that has centred homophobic, sexist and transphobic pitfalls in favour of cheap scares and shallow storytelling. That’s particularly true of the early ’80s—movies like Cruising and Sleepaway Camp were actively, consciously caustic toward queer and trans folks, murdering us for pleasure or depicting us as violent, crazed killers. In The Slumber Party Massacre, the crude murders and naked women are imbued with a tangibly feminine and even homoerotic touch.

But don’t be fooled—this movie is not some erudite examination of queer longing and female friendship. This is no Portrait of a Lady on Fire—this is The Slumber Party Massacre.

“Cheap thrills are to be found here, but the extended focus on these women’s lives enriches the film.”

After a series of hilarious fake-outs (including a particularly tense one where a character knocks on a front door and nearly gets drilled in the face by… someone making an innocuous peephole), the massacre begins. Russ Thorn shows up at the titular slumber party and bodies drop like flies in displays of luscious gore worthy of the genre this movie so effortlessly lampoons. Bellies are disemboweled, eyes are gouged out and multiple people are impaled. The women of the slumber party are stalked and killed until only a few remain. A brutal showdown begins between the wily women of the sleepover and the deranged man wielding an eerily phallic power tool.

The movie’s climax epitomizes the ridiculous, heavy-handed melding of feminism and VHS slasher tropes that makes The Slumber Party Massacre so uniquely watchable. If you’re hoping for a movie with gore and boobs, then this movie delivers on that level. But it also forces the viewers to question their own innocence. Unlike most movies of this era, the plot fixates entirely on Thorn’s female victims and their relationships with each other, the jokes they tell and the harmless weekend fun that drives them. The men in the movie, including and especially our drill-toting killer, are completely devoid of personality and hugely expendable. But the women feel a bit more realized, and their deaths feel senseless and brutal. Cheap thrills are to be found here, but the extended focus on these women’s lives enriches the film, allowing it to carve its own unlikely space in the canon of great horror.

Movies like Scream, Jennifer’s Body and 2018’s Halloween would go on to perfect the female-led horror satire that The Slumber Party Massacre gestured toward. But after nearly 40 years, Brown and Jones’ film is finally getting the recognition it deserves. A remake, which has been met with positive reviews, was released this month, and the original frequently appears on modern best-of lists. The Slumber Party Massacre is a veritable diamond in the rough. It’s about time someone drilled it out.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra