In a Las Vegas restaurant, in another time, a man strides into its back room, interrupting a party. He kisses his friends on the cheeks, then tosses a casual greeting over his shoulder: “Happy birthday, Stassi. Frank, suck my cock.”

Matters escalate, as matters always do. I hold my breath. A drink gets thrown. The party becomes a fight; the fight spills out of the restaurant and into the parking lot, where the same man continues in the same vein: “Enjoy my dick! Enjoy tasting my dick!” It gets physical—then finally production intervenes, swarming the scene, herding their charges toward different cars. Inexplicably, a third man takes off his shirt. Then they all do. They charge at each other, Hollywood muscles gleaming in the slick city lights, trying to slam their bodies into one another before their minders can leash them again.

It’s glorious. It’s peak television. It’s the stuff of my nightmares, reduced down to a 12-inch laptop screen.

I was volunteering on a crisis line at the beginning of the pandemic, and I found myself repeating over and over that the situation was exacerbating and compounding our existing trauma reactions. Hypervigilance is a common after-effect of trauma. In light of COVID-19, we were constantly on guard, waiting for the anvil to fall—familiar ground for many of us. With one hand I clutched my phone; with the other, I gripped a fold in my blanket. I kept my feet flat on the ground. I breathed slowly between calls.

The thing about conflict avoidance is that it’s a misnomer. Obviously I am conflict avoidant; it goes without saying that I was the kid who couldn’t watch Disney movies, or cringe comedy, or horror movies, or anything with more realistic stakes than your average Bugs Bunny cartoon. But the reality is that conflict mostly can’t be avoided: it can be soothed, pacified, minced around, but it’s still there in the middle of the room, sucking up oxygen, waiting to blow. And that’s only conflict between people. Zoom the camera out wider and the concept of conflict avoidance becomes kind of silly. You can’t avoid capitalism, homophobia, transphobia, racism, rape culture, COVID-19 or the rest of the oppressive structures that undergird our society.

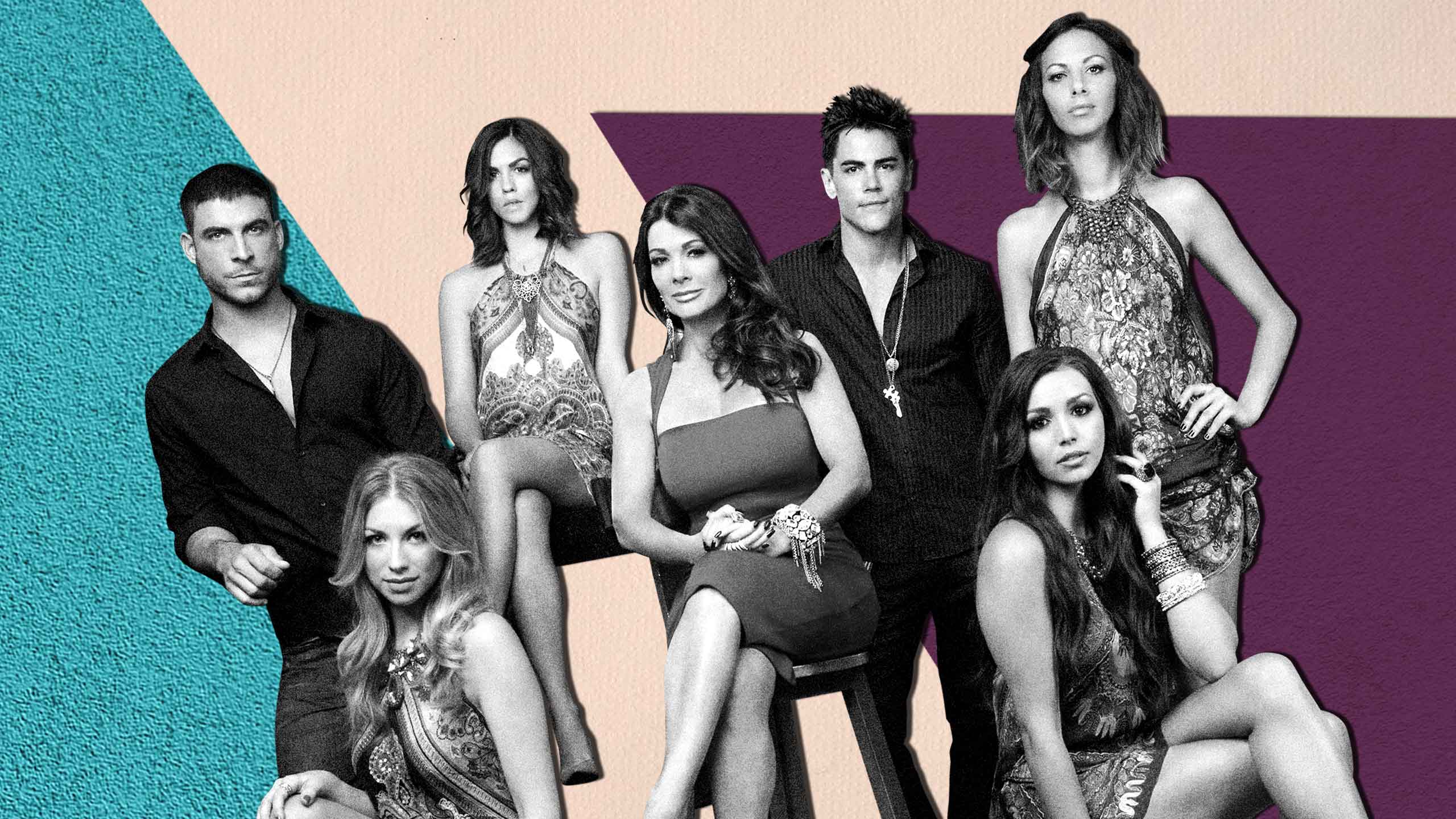

My wife—a genius—eventually suggested that we rewatch Bravo’s Vanderpump Rules to decompress during my shift breaks. Let me explain Vanderpump Rules Season 1 in 50 words or less: everyone works at a restaurant owned by Lisa Vanderpump of the Housewives pantheon. A rumour spreads that waitress Stassi’s bartender boyfriend Jax cheated, but none of their friends believe it. Stassi tries dating this other guy, Frank, but her friends hate him. Stassi disinvites Jax from her birthday trip, but he shows up anyway. This is not, in other words, a particularly relaxing show—yet I found myself devouring the first season like it could fill an empty pit inside of me. For the first time in my life, I wanted conflict. I wanted the fireworks. I was hungry for shit to go wrong, as wrong as it can possibly go.

I explained it to myself thus: during the pandemic, life as we knew it receded, and something else took its place. As my own life began to feel less real, I found myself needing a dose of reality.

“I was hungry for shit to go wrong, as wrong as it can possibly go.”

Time passed, as it does. IRL, shit went wrong, and then got worse. Like Jax waltzing into a Moroccan restaurant on the Vegas strip in the middle of round-whatever drinks, an old ghost from my life—a person I had disinvited from the proverbial party—came suddenly to the fore. Old wounds tore open. But worst of all, there was nothing I could do about them; time and COVID-19 and my own conflict avoidance built me a horrible torture machine of absent-presence. I couldn’t escape my thoughts; they were all I had to hold onto.

One of Stassi’s friends tells her, before the party fiasco, that things with Jax might get better. “Once the storm settles, things work themselves out, but you have to be proactive about it.” A second friend agrees: “Not effortless, effortful.”

The pandemic has been one long stasis, fundamentally anti-closure. How then do we resolve our unresolvables? How do we be proactive, put those parts of ourselves to bed, so that we can focus on all that’s presently wrong and hard? I found myself haunted by the what-might-have-beens. If I had said more, would they have apologized? If someone else had intervened, might I have gotten out earlier? I quit the crisis line, too busy with a crisis of my own. I burrowed deeper into the heterosexual theatrics of Vanderpump Rules.

In a dark club, a drunk Jax promises, “I’m gonna change everything. I’m gonna change overnight. Everyone is gonna be shocked.”

Inevitably, they will not.

Stassi responds, “I can’t! I love you! I can’t!”

Of course, she does.

There’s something about reality TV conflict—the high melodrama, the weird homoeroticism, the absurd schema of it—that’s actually kind of comforting. It has a Looney Tunes sensibility. Like in a comedy sketch, or a panto, there’s a formula: conflict, rising tension, outburst, implosion and recovery. Lying in bed, my wife heckling at my side all the while, I got to watch the whole process in real-fake time, in a safe setting, between universally terrible people that I didn’t care about. As Stassi and her friends asked each other “How? How did that happen?” and “Who are you? Who are you? Who are you?” I could revisit the questions I was asking myself weekly in therapy and see what was funny in them, not just what was sad.

Of course, by next season, everyone’s back to their old tricks. Sure, it’s for TV, but maybe there’s a grain of truth: conflict doesn’t have to mean growth and healing. It’s not a perfect path, and sometimes it leaves people unchanged. Sometimes—as was so often the case in this pandemic—you have to do the changing all on your own.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra