During Toronto’s seemingly unending COVID-19 lockdown, one day bleeds into the next. Amid the unrelenting monotony of household chores, writing deadlines and screaming cats, my most consistent source of levity and empathy is a WhatsApp group chat.

“Today’s personal mood board is brought to you by being called out by your search history,” Odessa Broomes, a 24-year-old Black lesbian with impeccable style (think Wiccan crossed with ’90s goth), types into the chat on February 22, 2021. The screencap they share includes the queries: “can you overdose on Zoloft,” “how to get your life together,” “COVID-19 Toronto” and “carrot muffins whole wheat.”

The group chat consists of: Odessa; Dorde “George” Radosavljevic, 25, a dreamy tattooed gay man from Serbia who’s in Toronto to study clinical psychology; Jay Austin, a 25-year-old gender-neutral queer person who has a talent for makeup I deeply envy; and me, a 30-year-old bisexual writer in a long-term hetero relationship. We all fall under the LGBTQ2S+ umbrella, but we share another important connection: we all have borderline personality disorder (BPD).

People with BPD experience extreme levels of emotional intensity, impulsivity, a poor sense of self, a crippling fear of abandonment and a slew of associated symptoms that can range from panic attacks to self-harm. “Lacking emotional skin, [people with BPD] feel agony at the slightest touch or movement,” explains the oft-quoted Marsha Linehan, clinical psychologist and BPD specialist. This can affect a person with BPD’s ability to sustain long-term interpersonal relationships. We’ve had other people with BPD come and go from the chat, but the four of us have nurtured and maintained our impromptu support space since we met during a skills training group at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in 2018.

BPD is still a poorly understood disorder, and people diagnosed with it face high levels of stigma not just from the general public but from healthcare providers. BPD is thought to be more common among the LGTBQ2S+ community—a 2008 study found people with BPD were 75 percent more likely to identify as gay or bisexual than comparison subjects with other personality disorders. We all come to the group chat from different backgrounds, with different trauma, for different reasons. Jay best captures why it’s such an important safe haven for us during a one-on-one interview: They share the Greek myth of Atlas, condemned to hold up Earth for an eternity. “It was that he had to do it alone, which is the true punishment. We have to carry a lot around. It’s only really punishing once we are left to handle it all alone.”

“We seem to inherently know how to comfort each other—a deeply felt linguistic shorthand that developed effortlessly.”

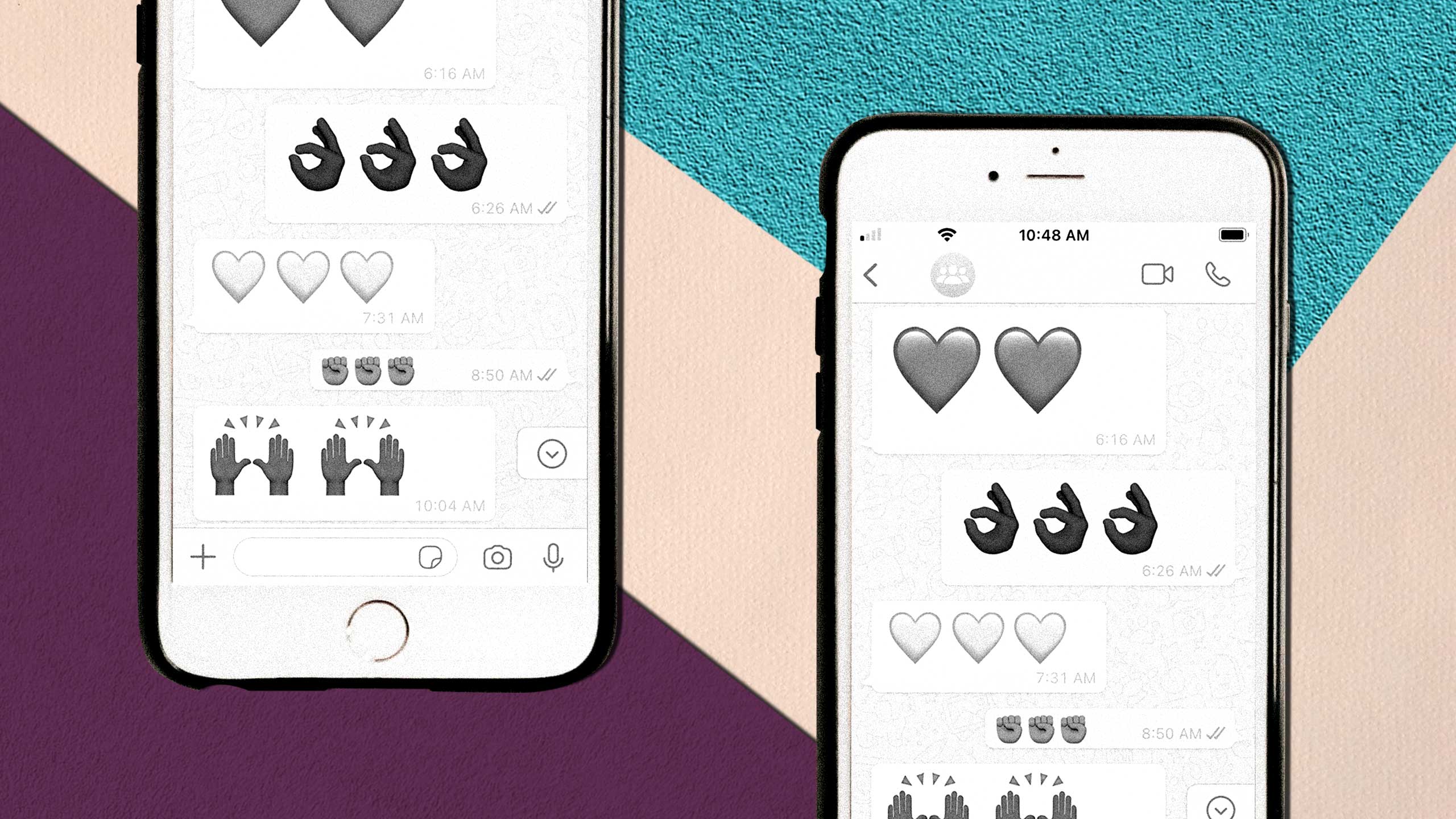

The four of us had been making good strides in our recovery journeys, and then the pandemic hit. New anxieties blossomed, panic attacks returned, and despair wrapped its familiar tendrils around us. According to a study released in December 2020, we weren’t alone: 61 percent of people with pre-existing mental health conditions reported deteriorating mental health due to the pandemic. Luckily, we could turn to each other for support. Despite our differences, we share a penchant for coping with trauma through gallows humour, and we seem to inherently know how to comfort each other—a deeply felt linguistic shorthand that developed effortlessly.

The pandemic provoked different reactions in each of us. At the onset, Jay struggled with anxiety, paranoia around getting sick and fears about the future. “Trying to calm the screaming lizard brain,” they admitted in March 2020. I reminded Jay that they were young, and likely to recover if they got sick (those were more optimistic days). George, never one to miss a beat, jumped in with a cheeky, “Or win the lottery and finally return to the void.” Today, Jay works as a security guard in a psychiatric hospital ward, and is pursuing a career in social work.

Odessa was also grappling with an anxiety disorder brought on by the pandemic: agoraphobia, the fear of crowds, public spaces or being trapped in places it’s hard to escape from. “I’m going through that cycle of, ‘let’s get motivated, workout maybe, and figure out what [I] want to do with [my] life that doesn’t make [me] want to die,’ and ‘I’d rather flay off my skin than become a functioning human,’” they said in February 2020.

“We’re in a pandemic,” I said. “Fuck functioning. I had a panic attack in a parking lot this week!” Though Odessa has recently felt aimless in their direction in life, they dedicate a significant amount of their energy advocating for LGBTQ2S+ and BIPOC communities.

“The group chat became a virtual communal space we could access on our own terms.”

Even prior to COVID-19, the accessibility of the group chat was its greatest function. Corralling people with BPD for an in-person hang was a bit like wrangling cats—our availability dependent on our moods, which are as unpredictable as the weather. The group chat became a virtual communal space we could access on our own terms. When the city’s public queer spaces were deemed non-essential and closed, the chat was the only space I could “visit” where I felt understood and didn’t have to hide parts of myself to fit in.

George and I dealt with our fair share of mental health setbacks during the pandemic, but navigating our romantic relationships during lockdown proved most challenging. The cause of BPD is unknown, but it’s thought to be linked to genetics and growing up in traumatic or invalidating environments. Though I’m six years into my relationship, and George has been with his partner for more than a year, the maladaptive behaviours our upbringings ingrained into us makes it agonizing to communicate our feelings and emotions to our partners. Last winter, desperate to brainstorm and share strategies for safe communication, George and I bubbled ourselves and our partners together for a productive and cathartic indoor meal.

On February 8, 2021, George sent a meme to the group of a skeleton wearing fairy wings and a tutu that reads, “When you’re dead inside, but your best friend needs emotional support.” To know I have a reliable and nonjudgmental space free from stigma and brimming with humour has helped me through the darkest days of the pandemic.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra