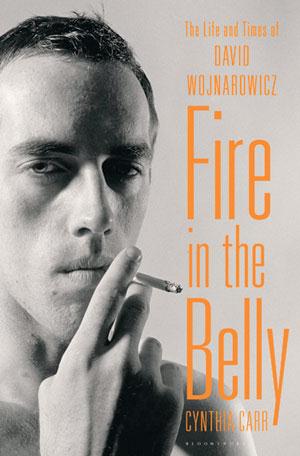

Cynthia Carr's new biography of David Wojnarowicz, Fire in the Belly, argues for his place in the canon of late-20th-century American artists.

In the fall of 2010, 11 seconds of out-of-context imagery brought the name of poet, author, visual artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz back into North American consciousness.

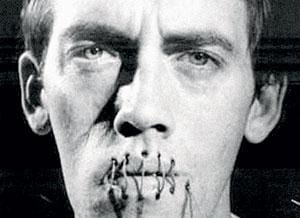

The occasion was the removal of an excerpt of Wojnarowicz’s video work A Fire in My Belly from the Smithsonian Institution’s retrospective Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture. The Catholic League misinterpreted a sequence showing ants crawling over a crucifix as blasphemous and raised the reactionary alarm. The group’s lobbying resulted in the removal of the work from the exhibition.

It’s highly doubtful that Wojnarowicz’s censorious detractors saw the complete work — or, for that matter, were even able to pronounce the artist’s last name.

The Hide/Seek affair serves as a fitting curtain-raiser for journalist and author Cynthia Carr’s magnificently researched new biography, Fire in the Belly. Through 600 pages of fascinating and stylish prose, this weighty tome argues heroically for Wojnarowicz’s place in the canon of late-20th-century American artists.

Carr covers Wojnarowicz’s tumultuous childhood, his years as a street hustler in New York City, the burgeoning success of the East Village art boom of the 1980s, and the artist’s final years as one of the moral centres of the AIDS crisis.

She draws on extensive interviews with Wojnarowicz’s family and friends, as well as his diaries and autobiographical works to construct her narrative. “What David did when he started talking about this life,” she says, “was to create a kind of myth as a sort of cloak [which] was a way to hide.”

Carr — who spent five years writing Fire in the Belly, including a marathon final year-and-a-half in which she paused only to observe Christmas Day — manages the tricky feat of separating Wojnarowicz’s self-generated mythos from the artist’s lived history. What emerges is a nuanced portrait of a complex, often infuriating, always compelling and intensely passionate artist.

For Carr, Wojnarowicz’s self-mythologizing was an attempt to pare down his life in order “to create this persona of the tough ex-hustler.” Though according to Carr, who knew Wojnarowicz personally, “David was not that way. He wasn’t a tough guy in his dealings with people; he was actually pretty sensitive.”

One of Carr’s early revelations was that “David did not understand the pathos in his own story,” and consequently, “he hid things that he didn’t need to hide, and he felt that if people knew the truth about him, people wouldn’t like him.” To Carr, “the central struggle in his life was about how much he could reveal.”

Fire in the Belly also recounts Wojnarowicz’s long tour of duty in the culture wars of the 1980s — specifically, his battle with arch-conservative demagogue Jesse Helms.

Helms, a Republican senator and virulent homophobe, proposed legislation that sought to prohibit the National Endowment for the Arts from funding artists who “promote, disseminate or produce obscene or indecent materials.” Wojnarowicz’s explicit, uncompromising work often led him into the crosshairs of the Helms-led war against the NEA, an organization that supported some of the most marginalized, and ulti-mately iconic, artistic voices of the era.

At the end of his life, Wojnarowicz contracted AIDS, which would eventually lead to his death in July of 1992. Although, according to Carr, he never wished to be viewed as an “AIDS artist,” Wojnarowicz’s ferocious political works — his searing memoirs, large-scale multimedia collage work, photography, performance art and films — remain some of the most stirring artistic artifacts of the AIDS crisis.

“I think by the end of his life,” Carr says, “he was a figure with a kind of moral authority,” and, she adds, “I think he’s very heroic.”

With Fire in the Belly, Cynthia Carr has erected a proud testament to the enduring power of David Wojnarowicz’s intellectual and emotional honesty, howling rage and brazen heroism.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra