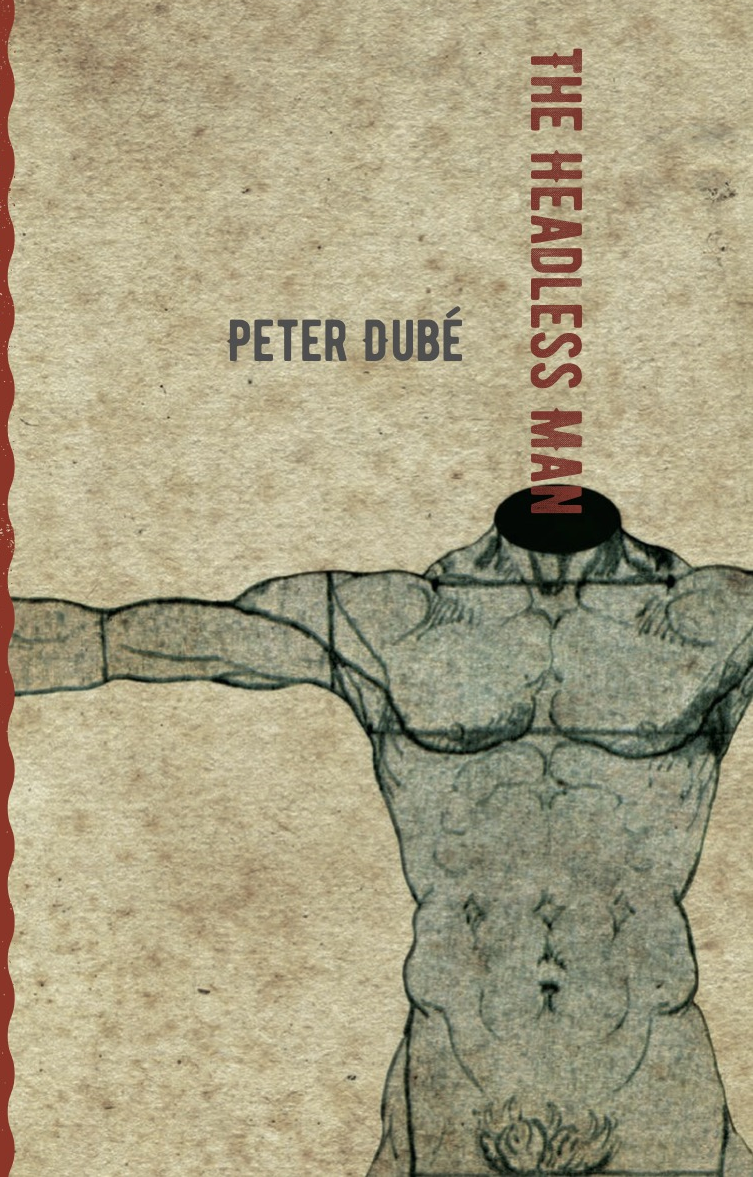

Peter Dubé is not a light read. His twelfth book, The Headless Man, is a surrealist prose poem inspired in part by the early 20th-century work of French intellectual Georges Bataille. It follows the story of the eponymous headless man as he is born and begins to gauge his connection to the outside world, ultimately engaging with the unnamed city and becoming a sexual being.

Dubé’s work is impressive in how it shifts gears, seemingly effortlessly: one moment riffing on Greek mythology, the next on a screaming-in-Technicolor screening of the landmark queer film The Wizard of Oz, then a visit to a strip club. And Dubé makes these otherworldly connections work, somehow drawing us into the world of his headless man and making it palpable; the writing is hypnotic, as if the author is speaking a singular language of his own creation. When our headless protagonist watches a stripper, moods and ideas rub up against characters: “He wonders why, again, why the passage of the dancer generated breeze strikes his intimate flesh like violence when the gloom does not. Then the beautiful naked man moves forward, sucking up light and shadow alike, and the Headless Man shakes. He sweats, feeling it.”

I spoke to Dubé from his Montreal home, just as the news broke that The Headless Man had been longlisted for Canada’s ReLit Award. (The poetry award ended up going to Simina Banu for her book Pop).

Being familiar with your oeuvre, I know you love surrealism. Tell me about what inspired this book.

I do, indeed, love surrealism. Its vision of a world far richer and more complex than is generally acknowledged, and its unwavering commitment to poetry, freedom and imagination, strike me as invaluable. As does its commitment to the simultaneous transformation of the world (external structures: political, social) and life (internal or psychological structures). In these, and many other ways, it seems to me one of the few worldviews or “practices of life” sufficient to address contemporary awfulness. For The Headless Man specifically, I found inspiration in the work of Georges Bataille, often seen as a “dissident surrealist” or a fellow traveller of the movement. It is from him (and his collaborator, Surrealist painter André Masson) that I took up the image of the headless man, whom he called the “acéphale” and deployed in the context of a secret society and magazine he founded. In my book, I transform the figure into a character able to move through the world and interrogate hierarchies of value (sexual, political and others). For example, the head as the seat of reason versus sensation or feeling, more rooted in the body. Or the head as the “ruler” of the body or the body politic.

I know that you feel there is a strong connection between surrealism and queers. Can you talk about the surrealism-queer axis?

What a great, but complicated, question. In fact, I am presently working on a theoretical/critical book about this very nexus. It is something to which I’ve given a lot of thought over the years, but I’ll answer as concisely as I can. Both surrealism and gay liberation (especially the early years of the organized gay movement and its writing, which are particularly generative for what I’m trying to work out, though there’s lots of important stuff written during the AIDS crisis years as well) are what I refer to (borrowing from [Frank] Browning) as “cultures of desire.” Both these intellectual/political tendencies centred desire, love and feeling in their thinking, and saw them as meaningful ways of organizing life and the world. And both, as importantly to my mind, were built on socialist foundations.

You make a number of pop culture references in the book. How does cinema inform your writing?

As a little boy I, like many gay boys, was obsessed with movies and my devotion to cinema has only grown greater with the passing of the years. I’ve watched—and still watch—a huge range of cinema across all sorts of genres and enjoy soaking up the wild variety of stories thus made available. So I’m a fan, for sure, but as a writer I often watch extra carefully and with an eye for form. Since cinema is (except perhaps for some forms of experimental film) essentially a storytelling medium, I keep an eye peeled for cool narrative tricks. There’s no doubt that years of taking in visual storytelling, for example, has contributed to the imagistic emphasis in my work. Plus, my study of film editing might be a factor in how I use juxtapositions, and my concern for significant detail. However, I have to note that I’m certainly not the only writer to have plunged into cinema so deeply and been inspired by some of its techniques. John Rechy, for example, has done so quite explicitly.

I’m inspired by your output as a writer, given that you have a full-time college teaching job. What does a writing day look like for you?

My writing days vary with the season, actually. What happens during the teaching semesters is quite different from what happens between them. I try to write every day in the summer, for example, but while a term is running I’m lucky to get in a morning of work once in a while.

“I like to start writing with my first coffee. There’s something in the early hours of the day that lets my imagination flow.”

I am a morning writer. I like to start writing with my first coffee. There’s something in the early hours of the day that lets my imagination flow. The door between the unconscious and the conscious, the waking world and the world of dream, is still a little bit ajar and all sorts of thoughts, visions and images can pass back and forth. That’s when I tend to do the actual creation of new pages, afternoons are better for editing and shaping. And evenings are time for me and my man. I do keep my notebook by my side even then, however, for any weird ideas that just pop into my head when chilling.

What would you say are your biggest influences as a writer?

Besides the Surrealists, I’d have to say gay liberation writers have been vital. In particular, the “New Narrative” group, an umbrella term for a literary coterie most often understood to include Robert Glück, Steve Abbott, Bruce Boone and Sam D’Allesandro, among others. Their simultaneous embrace of explicit sexual representation and highbrow literary theory is inspiring and exciting to me, as are their ideas about writing as a practice rooted in community.

“Surrealists don’t merely tell the reader what happened, they give him the whole moment: what happened, what the character felt and thought while going through it, the sensory detail.”

What joins them to the Surrealists, in my mind, is that both groups are writers of experience in the largest sense. They don’t merely tell the reader what happened, they give him the whole moment: what happened, what the character felt and thought while going through it, the sensory detail and emotional texture of things. That’s something I find very powerful.

You are a voracious reader. If people only have time to read one book this summer, what would you suggest it be?

It would be tough to narrow it down to just one, so I’ll give you two compelling titles. Personally, I recently enjoyed both Amy Hale’s Ithell Colquhoun: Genius of the Fern Loved Gully, a deeply researched and far ranging biography of Surrealist artist and occultist, Ithell Colquhoun, and the shattering but fascinating History of Violence [by Édouard Louis].

You and I lost a mutual friend to suicide during the pandemic. Losing artist and writer Richard Vaughan was intensely painful, and it was felt across Canada and throughout the global literary community. How does grief impact you, and how have you processed his leaving us?

Richard’s death was utterly wrenching for me. He was a very dear friend and I loved him. I still do, really. We shared a fairly verbal friendship and no topic was off the table for us, and we talked about absolutely everything and anything with giddy enthusiasm and complete frankness. Needless to say, we laughed a lot. Richard once wrote of our chats that when we got started we could “scald the heavens.” And boy, did we. I frequently replay some of those conversations in my mind so I can, at least imaginatively, hear his voice again. If, as I believe, “what is remembered lives,” I can keep him with me this way. But his actual real-world companionship is irreplaceable and I’m still grieving hard. I think I will be for a long while yet.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra