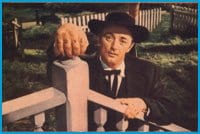

TERROR ON THE LOOSE. The spellbinding The Night Of The Hunter stars Robert Mitchum as a murdering man of God on the hunt for treasure and the children who know its location.

“And a little child shall lead them.”

Charles Laughton was the singular stage and screen performer of his day, a consummate artist who embodied such legendary characters as Henry VIII in The Private Life Of Henry VIII in 1933, Captain Bligh in Mutiny On The Bounty in 1935 and Quasimodo in The Hunchback Of Notre Dame in 1939. From the beginning he was told he could never succeed with a face like a “departing pachyderm” (his term) and his conspicuous paunch, but he forged an astounding career on his own terms, not only as an actor but as an orator, teacher, filmmaker and all-around aesthete.

Laughton’s only feature film as director, The Night Of The Hunter from 1955 (screening at Cinematheque on Sat, Nov 25), is one of the most memorable, idiosyncratic achievements in US cinema.

Where did it come from?

Born in 1899, Laughton’s rise as an actor on the late-1920s London stage was nothing short of meteoric. He brought an often overwhelming physical and emotional intensity to his roles. After a string of successes he left for Hollywood where he created several canonical performances over three decades with directors like Cecil B DeMille (he played a queeny Nero in 1932’s The Sign Of The Cross) and Leo McCarey.

Laughton invested so much of himself in his performances, he was frequently accused of hamming it up. This stubborn commitment flustered many directors, costars and critics, especially when accompanied by his effete manner and self-perception as an artist/intellectual rather than a humble craftsman. No one knew quite what to make of this scruffy, tubby and oddball genius.

Laughton married actress Elsa Lanchester in 1929 and remained with her until his death in 1962. But she found out early about what he called a “strong streak of homosexuality in his makeup” due to Laughton’s run-in with the police involving a male prostitute. Laughton had no shortage of boyfriends: He desired younger, beautiful, resolutely masculine men — polar opposites to the slob who had to transcend his bullfrog looks. Like many queers of his generation, Laughton had what biographer Simon Callow calls a lifelong “sense of not being right in the world.” He only embraced the camaraderie of his “own kind” — notably writer Christopher Isherwood — late in life.

After working closely with Bertolt Brecht on the play Galileo in the mid-’40s, Laughton went on to direct for the stage in the early ’50s. By this time, according to Callow, acting had become a way of, in Laughton’s evocative phrasing, “paying for ice for father’s piles.” Laughton wanted new challenges. Producer and impresario Paul Gregory made them happen. He organized Laughton’s wildly successful North American reading tour, where his legendary passion and skill for storytelling was put to good use. Then he bought the rights to Davis Grubb’s then unpublished purple novel The Night Of The Hunter for Laughton to direct. Laughton fell in love with it.

Laughton’s version of The Night Of The Hunter is a true work of art — a fairy-tale thriller turned Christian allegory. The book became a bestseller; the film was a box-office flop. Twenty years would pass, with Laughton long since dead, before it was crowned a curious masterwork.

In an astounding performance, Robert Mitchum plays Preacher, a self-righteous, switchblade-wielding seducer with “L-O-V-E” and “H-A-T-E” tattooed on his knuckles. During the Depression, he robs and murders widows in the name of spreading God’s gospel. His latest prey is Willa Harper (an amiably awkward Shelley Winters), whose husband robbed a bank out of desperation, killing two men in the process. He is hanged for his crimes, perhaps carrying with him the secret of where he hid the stolen money. Heading to Cresap’s Landing on the Ohio River, Preacher effortlessly charms the poor, dumb small-town folk (“My, that fudge smells yummy”) and soon marries Willa, hoping to get closer to the treasure. However, it is not this weak, wretched woman who holds the key, but the young Harper children, John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce). When John lets it slip to Preacher that he knows but will never, ever tell, the hunt is on.

The children soon escape downriver in one of the most beautiful sequences in film history, eventually ending up in the soft bosom of mother hen Rachel Cooper (silent-era icon Lillian Gish exuding, in Laughton’s words, “profound unsentimental goodness”), who protects them and the innocence they represent from the Preacher’s wrath. “I’m a strong tree with branches for many birds,” she boasts, and she sees right through to the evil core of Preacher.

From the first notes of Walter Schumann’s exhilarating score (with its wonderful hymns and children’s songs), you know you are in the presence of greatness — from Stanley Cortez’s black and white cinematography and Grubb’s mannered, folksy dialogue adapted by James Agee (and Laughton). Like a love letter to cinematic fantasy, it channels legendary DW Griffith — Gish was his greatest star and Laughton screened all Griffith’s films before shooting — and the stylized look of German Expressionism. It’s as nonnaturalistic and imaginative as Laughton’s own performances.

This mythic tale must have had many attractions to Laughton: The young, terrified boy made outsider because of his secret, or the eccentric — even cartoonish — portrayal of Laughton’s adopted country (with its religious fervour, sexual repression, abject poverty and lynch mobs). And it’s a family drama that places high value on nurturing and kindness unmoored from biological bonds (Laughton and Lanchester never had children).

The Night Of The Hunter’s stillbirth haunted the remaining years of Laughton’s life, which saw an aborted attempt at adapting Norman Mailer’s The Naked And The Dead, bravura performances in films by Billy Wilder and Otto Preminger and the chance to finally play Lear. Laughton died in 1962 after a horrifying, long-drawn-out battle with cancer.

We can now see his epic as the golden child it always was. To paraphrase its immortal closing words: It abides and it endures.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra