In 2017, R.O. Kwon found herself enraptured with a short story by Garth Greenwell that had recently come out in The Paris Review. The story, “Gospodar,” depicts a BDSM encounter between the American narrator and a Bulgarian man who asks to be called by the story’s title, a word that means “master” or “lord.” “But in his language there was a resonance it would have lacked in my own,” the narrator explains, “partaking both of the everyday (gospodine, my students say in greeting, mister or sir) and of the scented chant of the cathedral.”

The story, along with Melissa Febos’ memoir Whip Smart, which documents—among other things—Febos’ time as a professional dominatrix, evoked for Kwon the complexity embodied in kink. On the phone from her home in San Francisco, the South Korean-born American author of the critically-acclaimed novel The Incendiaries, tells me that, especially in contemporary books, movies and TV shows, she’s predominantly seen kink depicted in a flattening way. Often it’s a joke, and when it’s not, it’s intrinsically related to a violent character. “Very often, a TV serial killer will be a serial killer and kinky, as though the two, like, obviously go together,” Kwon says. Reading literature that included serious, complex, in-depth depictions of kink and BDSM inspired her, and she started wondering, “What if we could make a book like this?” She reached out to Greenwell, author most recently of Cleanness (in which “Gospodar” also appears), who agreed to work on the project with her.

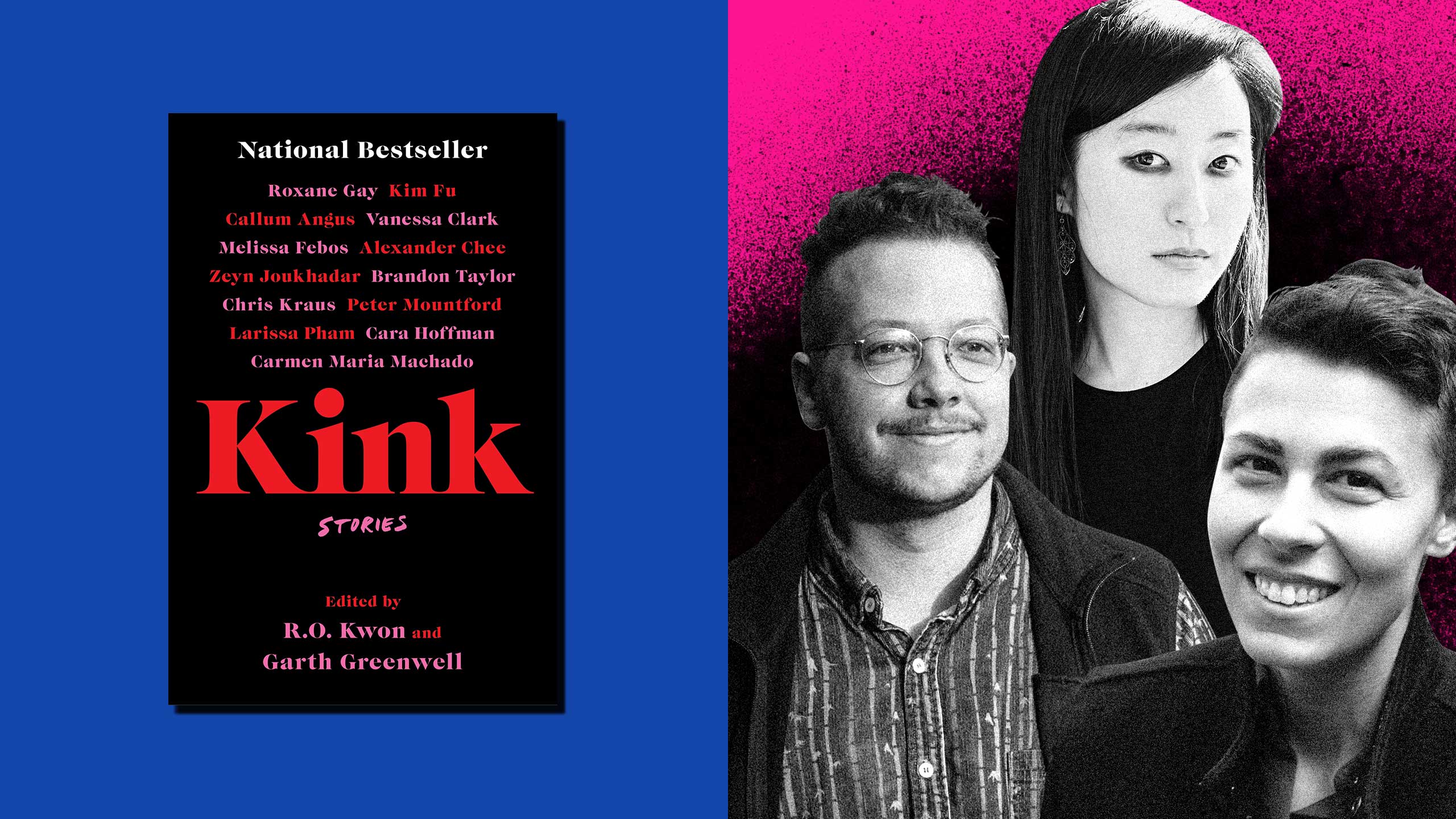

The result is Kink, an anthology of literary short stories featuring 15 writers, including Kwon and Greenwell. One might argue that there is something kinky about the anthology as an object: Authorial voices and imaginations live on top of one another when the book is closed, their order prescribed by the editors, pages of text rubbing against one another intimately. When opened, a book invites our touch as we turn the pages (or scroll or swipe at them on a screen), maybe even our spit if we’re the kind of reader who licks a finger first; if we listen to it, then the intimacy arrives through the various voices, their tones, the hard consonants and soft sibilants. We need not read it in the order given to us—we can read it bottom to top, middle outward, skip every other story. We have choice. There’s space for eroticism in the act of reading, and it is especially noticeable when reading the stories in Kink, which range from explicit sex to the subtext of embodied desires to the dynamics of transactional relationships to the intellectualization of sexual roles.

“There’s space for eroticism in the act of reading, and it is especially noticeable when reading the stories in Kink.”

“We really did want to have a wide variety of stories in terms of aesthetic style and what the stories [were about], but to get there, it was really, really important to both me and Garth that we never define kink for anyone,” Kwon says. This comes through in the stories’ many voices and styles, as well as in how kink is expressed within them. In Brandon Taylor’s story, “Oh, Youth,” the drama revolves less around the physicality of sex acts and more on the social dynamics between the main character, Grisha, and the older couple that’s housing him for the summer with the tacit understanding that he is sexually available to them. In Vanessa Clark’s story “Mirror, Mirror,” the narrator, Teena, a trans sex worker, is hired by a young man who is fascinated by her body—yet she works with this fetishization, and finds herself losing control in the midst of her own desire.

When Callum Angus, author of the forthcoming book A Natural History of Transition, sent in his contribution, “Canada,” he wasn’t sure it was explicit enough and was expecting that it wouldn’t fit the editors’ vision, he tells me. “But I was very happy to be wrong,” he writes in an email. “In this story as in my own life, I use kink as a means of exploring sexual pleasure not directly connected to or even associated with sex. This is partly because for me personally as a trans person with dysphoria, I can’t always access arousal and pleasure through my body. I turn to other kinky acts: Role play, service, clothing, anything that de-emphasizes the role of anatomy.”

I read “Canada,” which includes elements of climate catastrophe, as a story about leaning into change—as scary, terrible, necessary or joyous as it might be—and how crucial adaptation is to survival. Yet when I ask Angus about it, I discover he was thinking about an embodied kink that was completely different from where I’d located it. The kinkiest part of the story isn’t the sex, he tells me, but rather when one character puts on her lover’s binder and clothing and walks around town as if she were her own trans lover. “That living inside someone else, seeing what it might be like to be them, to feel the way people look at you differently, playing with roles and gender and identity—to me, that’s kink,” Angus says. “Ultimately it’s about exploring the edges of pleasure and bodies and pain and how they all coalesce to form an intentional, sometimes unusual and always thrilling corner of what it means to be human.”

Speaking to Angus reminds me why having spaces in which to talk about kink is so important, and how an anthology full of kinky literature can encourage such discussions. Like any other aspect of sexuality or sensual expression, there is so much that we can learn from one another, so many aspects of why and how we engage with kink that open up vistas into other realms of our lived experience as well. Indeed, all the stories in Kink bring in much alongside the sexually kinky acts or dynamics they portray. Peter Mountford’s story “Impact Play” is as much about family and shame as it is about the main character, Gavin, learning to embrace his fantasies “about spanking women, tying them up, using blindfolds, gags” and turning them into reality with a woman he loves. Roxane Gay’s “Reach” is as much about layers of trust in a relationship and the way trauma can be silent-yet-known as it is about the violent sexual pleasure shared between the narrator and their wife, Sasha.

“It’s about exploring the edges of pleasure and bodies and pain and how they all coalesce to form an intentional, sometimes unusual and always thrilling corner of what it means to be human.”

Zeyn Joukhadar, author most recently of The Thirty Names of Night, echoed how important kink in literature can be for its own sake as well as its role in exploring power structures and dynamics outside it. “As a trans writer,” he says, “I’m always aware of the tendency cishet folks have to sexualize my work (and my existence), and I’ve become increasingly interested in—and empowered by—exploring the idea of desire on my own terms.” His story, “Voyeurs,” starts and ends with a Peeping Tom who is watching a couple, Omar and Belén, who are both trans and also the only residents of colour in their neighbourhood. “I decided to begin with that outside gaze on the characters in a situation where the reader might expect to get some pleasure from watching the events unfold,” Joukhadar explains, “and then for the characters to turn that gaze backward onto the cis characters in the story—and, by extension, on the cis reader, reproducing that feeling of being watched and judged that trans people know so well.”

Most of the stories in Kink are written by queer writers and writers of colour, which was by design. Kwon tells me that she and Greenwell wanted “more people of colour than not, more people of marginalized genders than not” in the anthology. This is one aspect of what makes the book so invigorating: These stories explore the vast plurality of how kink is expressed and enacted by people inhabiting different bodies, genders and sexual orientations. “Kink should play the same role in literature as sex,” Kwon says, “and love and grief and war and friendship and all of it. It should all firmly have a place in literature.”

Kink, edited by R.O. Kwon and Garth Greenwell, is published by Simon & Schuster in the U.S. and Canada.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra