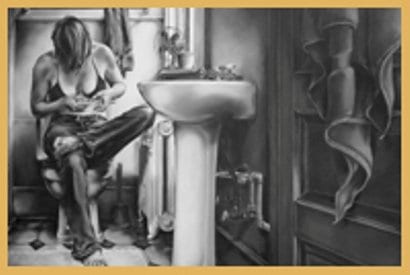

The two-tone painting hangs in her living room, subtle but unquestionably sexy.

Hearkening back to a style reminiscent of 1950s kitch, The Bathroom features a woman wearing nothing but jeans and a bra, seated on the porcelain at the far end of the room, clipping her fingernails. Staring at it feels voyeuristic, as if I’ve just walked straight into someone else’s private moment.

Patricia Atchison is unfazed. “I’ve heard a lot of people say, ‘I feel like I can walk right in’ about my paintings. I think that is kind of where the appeal comes from.”

Nearly a decade has passed since Atchison graduated from Capilano College’s two-year commercial animation program; the career choice was a natural extension of her childhood interests.

“It was a given my entire life,” the 30-year-old lesbian says. “You know the ad on TV: ‘Do you like to doodle?’ I did that when I was 10. They wrote me a letter and said, ‘Sorry, you have to be at least 14.’ At 14, they came to meet me and then enrolled me.”

Straight out of college, she was hired by the Montreal firm behind the children’s cartoon Arthur. She remained in Quebec for the next eight years, recently returning to Vancouver and immediately landing a job with the syndicated kids show Viva Piñata. She was recently promoted to art director.

While her day job is clearly something Atchison takes pride in, her exploration of photography-based paintings is unquestionably the centre of her passion.

“My first painting on canvas was in 1997,” she recalls. “I painted myself from my chin to my waist topless, much to my grandmother’s surprise. Initially, I had wanted to paint a woman, but I did not have any friends willing to pose naked for me, so I posed in front of the mirror and painted myself. That was the year that I came out.”

Fast-forward a decade and Atchison is just as determined, if not more so, to capture urban lesbian life on canvas.

“I want to paint images that are familiar to me, to my generation of lesbians and generations to come,” she says. “I want to paint images that are going to stand the test of time, go down in history as familiar places. I wish I could go back in time to the Lotus when it used to be in the basement; that is a part of a lot of women’s history. I want to capture queer lesbian life-my life-right now. “

One image she’d really like to capture is the entrance to Club 23 West, home to many lesbian nights and events. “I love the entrance of 23 West, the little window with medieval-looking, black cast-iron bars that separate you from the cashier, the sign that says ‘restricted.’ Twenty years from now, the bar might not be there anymore,” she says, “but ladies could look at that and go, ‘That’s Club 23!'”

She’d also love to “find a cool, old barbershop in the city and get the old barber to agree to pose while cutting a boyish girl’s hair in the shop.

“I’ve definitely been there,” she says. “You’re young and dykey and want the crew cut. It is typical lesbian behaviour yet at the same time controversial-stereotypical ‘manly’ lesbian getting a buzz cut. When most of America thinks of a lesbian, that is what they imagine. It is part of our community, it is controversial, it is misunderstood.”

For Atchison, it’s the subtleties of lesbian life and sexuality that are sexiest. “Ultimately, I want to paint stuff that everyone will enjoy, but lesbians can look at it and get it even more. That painting for example,” she points to The Bathroom, “has me in the bathroom cutting my nails. My mother didn’t understand the point of it, but lesbians are going to look at that and have their own thoughts about it.”

The strong but subtle image of a woman preparing her hands for a smooth sexual encounter captures the distinct type of unspoken statement Atchison strives to convey.

“Images are sexier with the clothes on,” she says. “I’d rather see a portion of a woman’s breast uncovered than totally naked because we get to fantasize, we get a story put in front of us to imagine.”

As for the future of urban lesbian life, Atchison admits to being concerned on a number of levels. “There was a piece in the gay paper in Montreal asking, ‘Are we becoming too straight? Are we emulating heterosexual society?’ That concerns me. I see that happening a little bit.

“In our community, you go to Pride and it is all about ticket prices and what you are going to wear,” she explains. “I remember where I could go to the bar and talk to everyone and it was very social and now it feels more cliquey and jaded.”

At the same time, she says, Montreal’s oldest gay bookstore closed a few years ago and was turned into warehouse space. “Those kinds of things are happening. What happened to protests? Why didn’t the gay community band together to save that bookstore? So many people were extremely upset but nobody did anything about it. There are occasions when people rise together, but we seem more concerned with what we’re wearing to the bar-and it shows.”

Despite her concerns, she feels optimistic about her future and the future of her fellow queer women. “We are going to be a strong force to be reckoned with,” she predicts. “The role models that women have to follow-Ellen, Rosie, Melissa Etheridge-women who step up to the plate and are open [and] produce what they want to produce. I have no fear in coming out and painting lesbian images; the more lesbians do that, the more we’re going to inspire other lesbians to follow their goals.

“I am painting for my community,” she says. “If I had the choice of two shows to go to, I’d go to the queer one. That is just who I am, my life, how I identify.

“I want to get out there,” she continues. “I want other artists to come with me, to show everyone else that it is a supportive scene. Something big, out and proud.

“The future of queer life for urban lesbians is to move forward and think without limits. Not to be afraid of obstacles, because if you are good at what you do, you’re going to go places. Being a lesbian is not going to hold us back anymore.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra