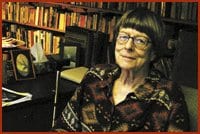

Canadian author, educator and activist Jane Rule’s kitchen overlooks a backyard surrounded on three sides by trees of nearly every shade of green. The intermittent whistles from passing ferries can be heard clearly from her home on Galiano Island. Large picture windows wrap her wooden house like a layer of cellophane.

“I used to be able to see the passage from here,” she tells me as she stands at the counter peeling apples. “But now the trees have obscured that. I think I like it better this way.”

Rule is preparing a Waldorf salad for our lunch together.

“Do you like cooking?” I ask.

“I’m not that interested in it,” she replies. “It’s a chore that has to be done. I wasn’t interested in domestic things. My mom said, ‘Never mind, if you can read, you can cook.'”

I notice a photo on the fridge of a smiling woman standing in snow. It’s Rule’s partner, Helen Sonthoff, who passed away in 2000.

“I should change that photo,” says Rule. “I keep up a seasonal picture of her. I guess it’s time to put the spring photo up.”

My visit was prompted by the news that Rule would be awarded the Order of Canada. She received word of her induction in true Island style. A neighbour picked up a letter for her at the local post office. On the envelope it read, “Order of Canada” in big, block letters.

“The letter said that I had to keep the news in strictest confidence, which was kind of hard when the postmaster and my neighbour both knew about it before I did,” she says. “I told them I couldn’t keep it in the strictest confidence. The best we could do was pretend we didn’t know.”

Rule has been a magnet for awards in recent years. Her latest medal was provided by the Atlanta, Georgia-based Golden Crown Literary Society, which gave her a Trailblazer Award Jun 9. She was inducted into the Order Of British Columbia in 1998. But she was particularly happy to receive the 2007 Alice B Reader’s Appreciation Award, which recognizes lesbian writers and showed up in the mail one day with a cheque for US$500.

“I think they deserve some publicity,” she laughs.

Rule is modest and light-hearted about accolades. She says most honours are given or withheld for the wrong reasons, but the fact that she, a lesbian artist and queer liberation pioneer, is receiving the Order Of Canada is not lost on her.

“Not enough women artists and gay people get it, so I decided to be gracious and accept it on behalf of us all,” Rule, who was born in the US, says. “I chose Canada 50 years ago. I’ve had a happy, productive life here and for Canada to choose me is kind of wonderful.”

Fifty years later, the queer community has come a long way, thanks in great part to trailblazers like Rule who stood up and spoke out long before it was socially acceptable.

Her first novel, Desert of the Heart, was published in 1964, five years before the decriminalization of homosexuality. It’s an unabashed tale of love between women, sexuality and romance. She couldn’t find a US publisher, so the first edition was published in the United Kingdom.

She has since written 11 other novels, worked as an English instructor at UBC, and contributed to The Body Politic and Xtra. She has always been a huge supporter and defender of gay and lesbian people. She’s also a visionary.

In recent years, she argues, queer people have focussed too heavily on the issue of same-sex marriage and efforts to present a more normalized image of us to the straight majority.

She views the push for same-sex marriage as an indication of the mainstreaming of gay and lesbian cultures. She believes that the queer liberation movement should move to free us from hetero-normative relationships.

“We should be campaigning against dependent relationships between adults,” she says. “We should be identified as individuals, not by our relationships.”

Rule calls marriage “privatized welfare” and cites the welfare rules as an example.

“You lose your ability to get welfare if your partner’s working,” she explains. “You don’t have to be married; it’s just if you’re living with them. It applies to common-law and if you have children you can’t get any aid for them; the partner has to supply it… My sense, which is counter to marriage, is to get the state out of adult relationships altogether, whether homosexual or heterosexual.”

Rule says that it is up to individuals, not the state, to decide who is the most significant person in their lives.

She also believes queer people need to have the courage to be more radical. The movement should focus more on youth issues, including sex education and tolerance in schools.

“I don’t think the gay community and the voices of the gay community have been strong on this,” she explains. “I think we’re afraid to deal with it because we are accused of being child molesters, so the way we avoid that is not to deal with adolescent and children’s issues at all. The trouble with any minority is that at a certain stage in its development it apes majority culture instead of doing something radical like working with youth.”

As for writing, Rule still does it but mainly for pleasure. “I don’t write anymore except for me,” she says, although she doesn’t rule out the possibility of writing another book.

“I may bring out another one,” she teases. “Nowadays I just get through the day. Helen used to say, ‘Being old takes a long time.’ Chores like washing your hair and making dinner take longer than they used to.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra