Margaret Kocuiba succinctly summarizes her reason for marching in Vancouver’s fourth annual Dyke March.

It’s important to hold a dyke march, she says, “because as women we have our own identities.”

The 69-year-old is the oldest member of Sisters in Sync, Canada’s first all-lesbian dragon boat team. She and her “paddling” teammates are marching down the Drive in matching t-shirts, just some of the many women who turned out Aug 4 for the largest-ever showing of dyke visibility on the Eastside.

It’s the day before the annual West End Pride parade and Kocuiba is looking forward to that too, but the Dyke March is more than just a celebration, she contends. “Coming to the march is a way of supporting our community.”

“We can join in with gay men tomorrow,” she says, walking along Commercial Dr. “Today,” she smiles, “we can join in with lesbian women.”

“Vancouver is an environment for freedom I’ve never experienced before,” she adds —”the freedom to be me.”

A few blocks back, as more marchers leave McSpadden Park at Victoria Dr and E 5th Ave, Wendy Oberlander picks up her bicycle and smiles at her four-year-old son Uri seated comfortably in the attached carrier seat. It’s not about the politics for him, she says. “He likes the music, the costumes and the having fun.” This is Uri’s second march.

For his mom, the Dyke March is a little more political.

“It’s important to have the visibility and be together and remember history,” Oberlander says, observing the increase in numbers at this year’s Dyke March.

Three years ago, “the first one was tiny,” she recalls. Her first dyke march experience was in San Francisco in 1993 when she marched with 10,000 other women.

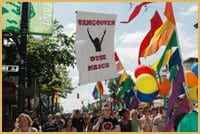

Thousands of women and a handful of men have gathered today to march to Grandview Park on Commercial Dr. People on the sidewalk watch from chairs set up in the shade outside buildings along the Drive. Some stop mid-shopping to watch the sporadically chanting, sometimes singing, often boisterous women march by. Store clerks with no customers lean out of open shop doors to catch a glimpse of the celebration.

Kristine Boisvert moved back to Vancouver in November after living in Montreal for four years. She is on security detail for the march, keeping the traffic and the women apart.

She says she felt compelled to volunteer “to do something for my community.”

“It’s important to have a dyke march,” Boisvert believes, “because we want to be surrounded by women. That’s the point of being lesbian, isn’t it?” she laughs.

Dogs sporting little rainbow bandannas around their necks strain on their rainbow leashes as they catch wind of the grass and the park, where an assortment of Pride flags and banners adorn the stage and clusters of rainbow-coloured balloons dance in the wind from strategically placed locations around the stage area.

“Pride is definitely important but this fills a different need for people,” says Dyke March co-coordinator Michelle Walker. “It’s really empowering for everyone to see everyone else here with you.”

Walker takes a breather from her march responsibilities to survey the crowd. She is very happy to witness everyone enjoying the event. Last year there were between 2,000 and 3,000 marchers, she says, “and this year it’s bigger.”

“This is completely different from the Pride parade,” she observes. “It’s more grassroots —as in, no corporate sponsorship.”

The march’s fundraising went smoothly this year, Walker notes, adding that the board “has always had a lot of support from the community in fundraising during the year.”

This year, the march’s board of directors was the smallest it’s ever been; Walker and her colleagues are actively looking for volunteers for next year.

“It’s been a lot of work this year but it’s definitely all paid off to see everyone having a good time,” she says, a seemingly permanent grin lighting up her face.

Volunteers with garbage bags navigate the crowd in Grandview Park; a reminder there’s a garbage strike happening in the city. When the volunteers arrived earlier at McSpadden Park for the pre-march gathering, they found it needed some cleaning up so they took on the task. Now, as people enjoy the post-march festival, they are reminded to please take home their trash.

George Smith sits on the grass near a fence, calmly observing the convergence of thousands of dykes in the park. His long, gray ponytail and beard complement the tattoos covering his tanned arms.

The 62-year-old explains that he used to come to the Dyke March with his wife, who recently died. “It’s tradition,” he says. “I’ll stay a couple of hours and then I’ll go home.”

The Dyke March, to him, is just another community festival. Participating in all the community events held in Grandview Park gives him a feeling of shared community —dykes included.

“This is what I like,” he says, standing as the music starts and moving closer to the stage for a better look.

Long-time activist in the dyke community Trigger, and her company, Girlgig Productions, volunteered again this year to produce the stage entertainment.

While she’s excited to attend the next day’s Pride parade and especially to watch her police officer partner of eight years march by, Trigger acknowledges there’s something different about women’s events.

“The Dyke March is important because it’s a women’s event. Women are always more inclusive and family-oriented in their events,” she believes. “It’s a family, kids, dog-friendly event,” she points out.

Trigger also serves on the Dyke March’s board of directors. “The women who started it had a vision to resurrect the march again and they’re such a great group of women,” she says. “I was happy to volunteer my services. It was a small but strong board.”

Like the rest of today’s board members, Trigger sports a black T-shirt with white letters running in a vertical line down her back: “Pride. Women. Visibility. Celebration. Family,” the shirt reads in a fitting tribute to the day’s vibe.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra