Smoothing linens with military precision is an unsung tradition in the janitorial arts. A properly made bed can console the itinerant, the broken-hearted, the homeless. Staging properties, she has learned over the years, is mostly about subtraction, about deleting personal history, something she takes very seriously. She continues to take things away with total exactitude, one after the other, until a purity in openness emerges, a balancing of light and air and material objects set in space; the lie of neutrality. This is the soothing of wounds, when complete; the calming of sorrows. Progress and satisfaction, here on earth.

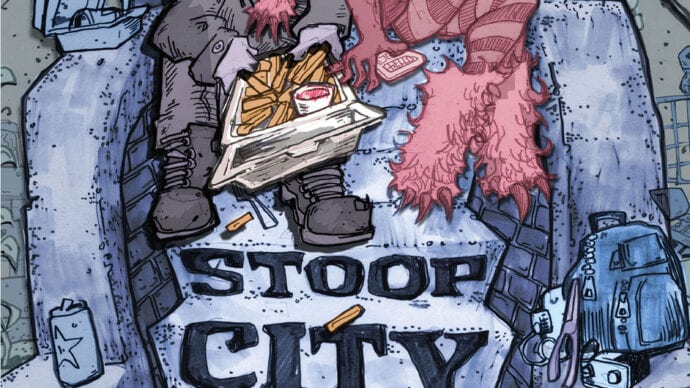

This is the ending of “How We Learn to Lie,” one of many wild and beautiful gems in Kristyn Dunnion’s new story collection Stoop City, out this month from Biblioasis (full disclosure: the publisher is a former employer of mine; I left before this book was acquired). Dunnion frequently ends her stories on evocative passages like this. Here, the protagonist has just stripped a house of the personality of its former owner, a broken-hearted lesbian widow who could no longer afford the mortgage. “The lie of neutrality,” the money shot that fuses the 17-page story together in its penultimate sentence, leads us toward a deeper truth. “Julia is kind of the enemy!” Dunnion says when I ask her about this story. The aforementioned protagonist and narrator of “How We Learn to Lie,” Julia is an upwardly mobile, straight white real estate agent methodically moving forward with her career, selling properties in gentrifying west Toronto, pleasantly and industriously executing the turnover of its residents. In a certain respect, it’s an anomalous story for Stoop City, which, with only one other exception, blooms with characters down on their luck, living with the lifelong effects of poverty, addiction, homophobia, racism, misogyny, houselessness and mental illness—a patina of shit and beauty running through Toronto (pausing in the middle for two gut-wrenchingly sad stories set on Essex County’s southern shores). “You walk through a street or open your window and you hear these random things flying in. I love that everyday magic,” she says. Her collection crawls with the interlocking life of a city—the beep of garbage trucks backing up during our Skype interview reinforces this in a cute kind of kismet. The characters, too, are linked in Stoop City, though it’s never overdone or ham-fisted; it’s subtle. “Whoever’s story it is, it’s always being undermined and infiltrated by someone who lives a different life from that character,” Dunnion says. After we get off the call, I turn that statement around a bit. I find I’m not sure I agree. Most of Stoop City’s characters are in parallel shit sandwiches. “Undermined and infiltrated” doesn’t exactly feel correct to me—I’d suggest something like “complemented and widened.” Julia takes part in a little undermining and infiltrating though—she does her job while coolly considering cheating on her boyfriend, which she doesn’t, but she does dump his ass out when she discovers he’s the cheater. From a bird’s-eye view, a reader might wonder what exactly Julia’s doing here in this particular collection—until the above ending. Julia’s measured attachment to her life and her job depends on erasure. “Deleting personal history is not just her history but it’s all history,” Dunnion says. “It’s a colonial mindset of taking and removing and smoothing over.” Is Stoop City a dark book? I don’t think so, though it gazes unflinchingly at bleakness. While there are plenty of sad parts—“Fits Ritual” and “Daughter of Cups” were particularly pit-in-your-stomach experiences for me—it’s also really fucking funny at points, and flecked through with a kind of celebration and joy. “This is the Time to Light Fires” and “Last Call at the Dogwater Inn,” the first and last stories in the book, respectively, both revolve around a recent death: An unnamed woman in “Light Fires” is mourning her girlfriend Marzana (remember the mourning widow from above? Bingo); a seething addict in “Dogwater Inn” discovers his friend and motel neighbour Jimmy has died. Grimness unspools as the stories moves forward. Marzana was cheating relentlessly on the woman and Marzana’s queerness was rejected by her family. Jimmy, a mentally ill Black man, died when he smashed out the windows to an electronic store and the police shot him down for “inciting a riot.” The book is dark, but Dunnion’s authorial voice never tips into despair, even if her characters might. It’s a nice move. The seething addict, having just taken a lot of Jimmy’s left-behind opiates, spins on Jimmy’s bed as the motel’s denizens crowd the room and remember Jimmy with beer and food—by sheer page-time, the story is more a celebration of Jimmy’s life than anything else. The mourning woman is rudely interrupted by, well, Marzana returning as a ghost, and their bickering tumultuous relationship resumes in a fashion parallel to their earthly form. The confused arrival of their couples therapist is a favourite moment:

Mindy pushes her glasses up her nose. “I’d like to remind you of my commitment to anti-oppressive practice and I think in this situation we, um, need to address the complex marginalization of the pre-deceased… I’d like to open the floor for—what’s your girlfriend’s name?” “We’re calling her Ghoster.” “Um, that’s not okay.” A shaft of light blasts the television. It turns itself on. The nauseating final scene of a film starring Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. Marzana’s secret shame: she’d watch, weeping in this very chair, and could not be consoled. “This is her doing?” “Who else?” I say. Mindy reaches for a tissue, sniffling. “Clearly we have a lot of sadness here and lost romantic possibility.”

During our Skype call, Dunnion and I talk a lot about the obligations of representation. She brings up the character of Hoofy from “Fits Ritual,” a gender-weird (in my headcanon, they’re trans) con artist and addict living on the street in a destructive relationship with a looker named Roam. “I don’t live in a shelter. I have spent time in shelters,” Dunnion says. “I work with people who are homeless. I work for people who live in shelters, and who choose not to as well. That community is not unknown to me. And is it my right to write that story? I’m not sure.” But she is sure of one thing: “I want people to stop walking by someone on the street and not think twice.

We discuss this again with “Light Fires.” The character Marzana is based on one of her exes. Writing the story, Dunnion says, was a way to deal with grief, and not just about that break-up. “I’ve lost a lot of friends in less than a dozen years, double that number,” she says. “At a certain point you just become numb, you stop feeling it as intensely. And I know people whose lovers have died while they’re still in a relationship, and I thought ‘Do I have the right to write this story? My lover didn’t die.’ But then I was like, ‘Everyone else died though.’ That grief was expressed in the story.” I’m grateful to Dunnion for articulating this. As discussions about appropriation and representation carry on through the literary world, it seems plain to me that a missing part of the discussion, specifically for authors writing characters with shitty experiences they don’t possess, is that of a relationship to those people and communities in real life, or emotional experiences that without question allow a creative way in. Certainly I think of this often as a transsexual reader—the cis writers who successfully create trans characters are usually those who’ve spent time around actual trans people. Not sharing most of the experiences of Stoop City’s characters, I’m of limited value in judging Dunnion’s book this way, but I do think her process as outlined above is part of how the book succeeds. “Fits Ritual” is maybe my favourite story in the book. The emotional undertow propelling it forward is the overwhelming, glitteringly sad and joyous feeling of the desperate love Hoofy has for Roam, even as Hoofy catches him getting way too friendly in a supposed con job with an upper-crust girl from Rosedale. Its tenderly bleak ending is not unlike how much of the collection feels: “Just ask your insides, I want to say to her. Ask your belly and your bowels and your tormented liver for the truth. Mine, doomed as they are, always soften at his touch.” Kristyn Dunnion will virtually launch Stoop City on Sept. 22 at 7 p.m. EST, with Shannon Quinn, Paige Cooper and Sybil Lamb.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra