The Skin We’re In: A Year of Black Resistance and Power by award-winning journalist Desmond Cole follows various activists, including Cole himself, over the course of 2017 as they each struggle against racism in Canada. The following excerpt is adapted from the book’s chapter on Black Lives Matter Toronto and its return to the city’s Pride parade. Cole revisits 2016, when BLMTO—then Pride’s honoured group—stopped the parade in a political coup de théâtre, connecting the action to the Bathhouse Raids of 1981 and the evolution of LGBTQ2 activism in Toronto.

Black Lives Matter Toronto was different from most Black activism I’d seen. Its organizing crew seemed to consist almost exclusively of Black women and Black queer and trans people whose voices, the organizers regularly emphasized, have consistently been marginalized within Black decision-making and community organizing. The group’s members all referred to themselves as co-founders. Many of the young organizers I followed in those early months, including Alexandria Williams, Yusra Khogali, Sandy Hudson, Pascale Diverlus and Rodney Diverlus, were students at local universities and were actively engaged in struggles on campus for free tuition, the creation or expansion of Black and African Studies, and better accessibility standards and services.

As I attended every BLMTO event I could, I noticed the organizers often hired American Sign Language interpreters for deaf attendees. BLMTO advocated for Black sex workers, for Black people who didn’t speak English, for Black Muslim people. The media rarely explored the depth of experience and advocacy among these Black organizers—instead, mainstream media coverage focused on the unlikelihood of BLMTO securing the approval of white people with its radical politics and unapologetic approach.

In Pride Toronto’s press release announcing that BLMTO would be the honoured group at Pride in 2016, it noted that BLMTO “continues to rally against sexual violence along with Take Back the Night, focusing particularly on the lives of Black women, Black Trans and queer people along the gender spectrum, Black people with disabilities and Black sex workers.” Pride said its staff and volunteers “all openly welcome the opportunity to learn from the coalition, celebrate their successes and give support to the continued fight for Black lives.”

Canadian governments and institutions have conducted very little research into violence against people who identify as intersex, two-spirit, queer, trans, bisexual, lesbian or gay. According to a 2015 study on human rights and trans people in Ontario, “trans people are the targets of specifically directed violence; 20 percent had been physically or sexually assaulted for being trans, and another 34 percent had been verbally threatened or harassed but not assaulted. Many did not report these assaults to the police; in fact, 24 percent reported having been harassed by police.” There is even less data about the specific experiences of Black trans people. But a lack of data can’t excuse a refusal to listen to Black queer and trans people, who keep sharing painful experiences of police violence.

BLMTO was one of many organizations with a presence at the 2016 Pride Week festivities, with a booth and volunteers and pamphlets. But organizers said they were not treated like most others by the police who’d been hired to patrol the festival. BLMTO member Janaya Khan described how cops continually asked the group for its festival permits, saying the harassment became so aggressive that group members alerted Pride Toronto organizers. Khan would later ask, “What does it mean if, in Pride, I am criminalized within it as a queer Black person, and I am criminalized when I leave it?”

Syrus Marcus Ware of BLMTO, who is trans and has spent two decades organizing spaces at Pride for Black queer and trans people, has noted that Toronto’s larger Pride community has historically ignored the specific dangers and circumstances of Black queer and trans people. “The idea that we could be black and queer, black and trans, is unfathomable to too many people in our community. We don’t belong because they’ve never expected us there,” Ware said in 2016. Even as BLMTO accepted Pride’s “honoured group” acknowledgement in early 2016, its members expressed mixed feelings about the festival’s history with police involvement. “In Pride, there is often a delegation of police who are there, waving and shaking hands,” Khan said at the time. “And that’s not the relationship that black queer and trans people have, and racialized queer and trans people have with the police. It never has been.”

“‘The idea that we could be black and queer, black and trans, is unfathomable to too many people in our community. We don’t belong because they’ve never expected us there.'”

We can trace this truth back half a century, to the 1969 New York Police Department raid on the Stonewall Inn and the subsequent uprising of queer people in that city that energized communities across the United States and beyond. Stormé DeLarverie, a Black queer entertainer, was reportedly one of the first people arrested during that raid of the Stonewall, a club where the city’s queer community often gathered. But Stormé fought back, recounting years later, “The cop hit me, and I hit him back.”

The courage of Stormé and others inspired hundreds of people to pour into the streets to support those being arrested. The next night, thousands more mobilized to protest the raid. A Black trans woman named Marsha P. Johnson, who also frequented the Stonewall, reportedly climbed a lamppost and dropped a brick through the windshield of a police car.

BLMTO highlighted the ongoing mistrust of police by advocating for Sumaya Dalmar, a 26-year-old Somali trans woman found dead in a Danforth Village home in February 2015. Police said they found nothing suspicious about Dalmar’s death, but acknowledged they’d received calls suggesting she had been murdered. “Pride is about being able to live with dignity,” said Leroi Newbold of BLMTO in a 2016 interview. “And we can’t live with dignity when our Black trans sisters can be disappeared and murdered within the vicinity that we live with impunity, and the police aren’t held accountable with finding out what happened to them, such as what happened to Sumaya Dalmar.”

“There was even a Pride in Corrections delegation of prison staffers, which included a bus with tinted windows. The Toronto Star had reported on this vehicle at previous Pride parades, describing it as ‘what looked like a prisoner bus decked out in rainbow flags.’ Does your parade have a prison bus?”

We have to consider Pride Toronto’s commitment to “the continued fight for Black lives” alongside the fact that the largest delegation at Toronto’s 2016 Pride Parade was a group of hundreds of police from across southern Ontario, including Toronto, Hamilton, Waterloo, Durham, York and Peel, and University of Toronto campus police. A video of the police delegation passing by a stationary camera is almost nine minutes long. Many officers were in full uniform and were carrying their weapons. There was even a Pride in Corrections delegation of prison staffers, which included a bus with tinted windows. The Toronto Star had reported on this vehicle at previous Pride parades, describing it as “what looked like a prisoner bus decked out in rainbow flags.” Does your parade have a prison bus?

Institutions and corporations that disproportionately harm queer people have invested heavily in branding themselves as queer-friendly—activists often refer to this practice as pinkwashing. One of the many police squad cars at the 2016 parade had a paint job with pink highlights and the words “Stop Bullying” plastered on it. As a former federal prisoner said, in writing about the connection between the corrections Pride marchers and discrimination in Canada’s prisons, “In terms of its treatment of people of colour and queers alike, correctional services should not be allowed to hide behind Pride’s flag.”

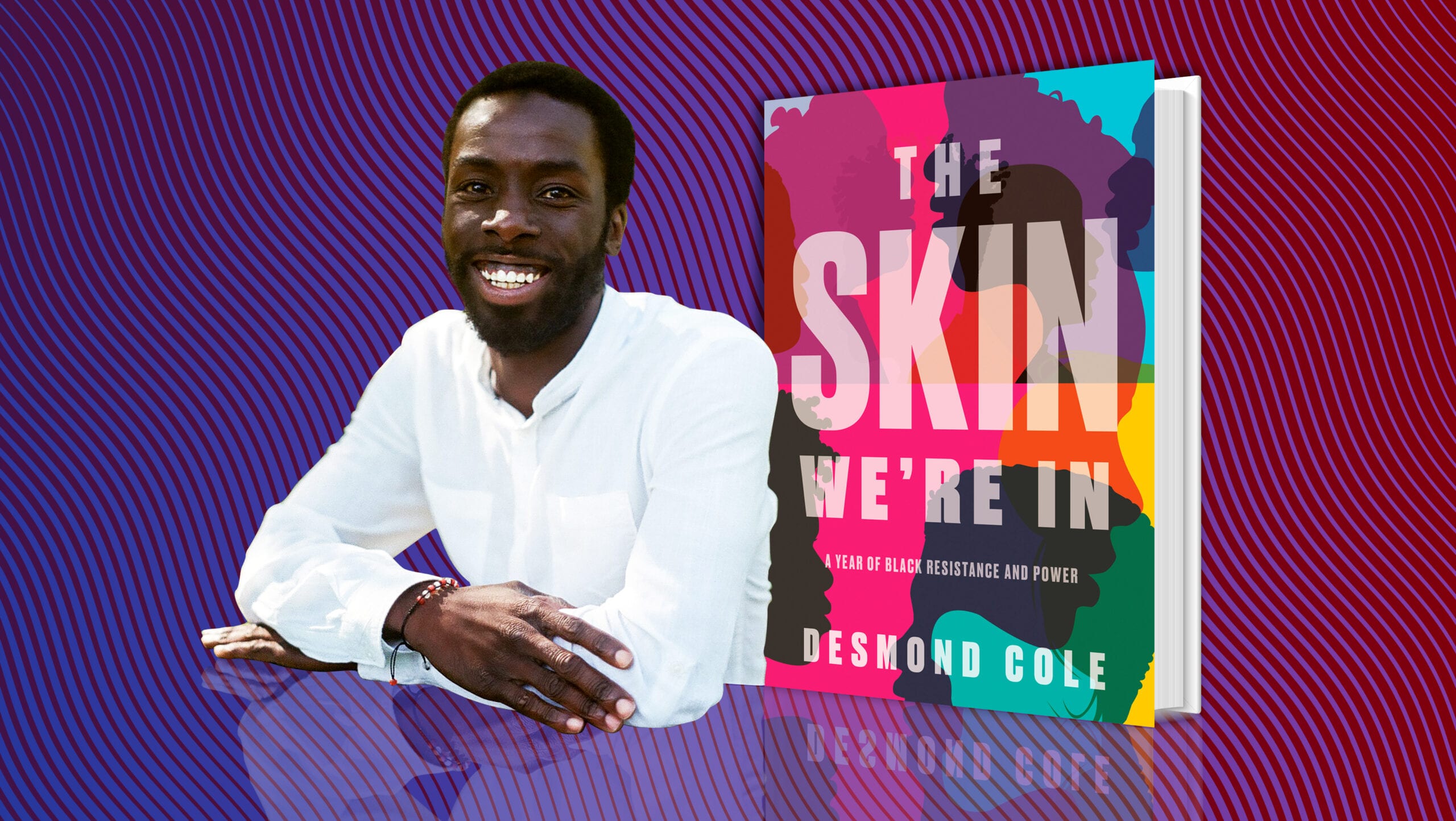

The Skin We’re In is published by Doubleday Canada. It will be available in stores on January 28.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra