TROUBLED TIMES. Every Time I See Your Picture I Cry is set in a community at the gates of hell. Credit: (Shelia Spence)

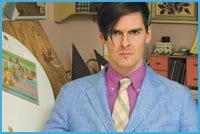

Fans have been impatiently waiting for more than three years for the world premiere of Winnipeg artist Daniel Barrow’s new “manual animation” performance Every Time I See Your Picture I Cry, copresented by the Images and Harbourfront’s World Stage festivals. Though Barrow promises to deliver the goods to his admirers, the piece is also a departure from early performances like Looking for Love in the Hall of Mirrors and The Face of Everything.

“I really haven’t had a significant span of time to gain the momentum I need to complete an hour-long video/overhead performance,” says Barrow. “But I’m so close to being finished. I’m really excited. It’s been a long way for me, so as a consequence it’s really kind of an important piece to me. I’ve spent a long time thinking of the story, watching it develop.

“I think we’re in a really serious and critical time on earth and it hopefully conveys a sense of urgency.”

Every Time is not only darker and more attuned to evil in the world, it also features a protagonist quite different from the passive, dandyish waifs and strays of his earlier work. “I wanted to write a new and angrier character, and I kind of don’t feel that I have the performance skills to pull that off without sounding whiny. It’s really hard to convey a sense of urgency without sounding self-serious. I don’t want to give the wrong impression. The piece is still very similar to everything else I’ve done – still funny and hopefully achieves a balance between shame and pride, tragedy and comedy.

“It’s different in that it’s a performance set in a community that stands at the gates of hell, which sounds very dark — and it is — but I’m still in the room to moderate the gloom and darkness.”

Stationed behind an overhead projector, Barrow — or more specifically his voice and his hands — has always enraptured audiences, who hang on to his every word and marvel at what optical delights can come from manipulating humble drawings on acetate. “I guess as I get older I feel a greater sense of responsibility with my work,” says Barrow. “None of my protagonists up until this point have cared much beyond self-preservation. But this is a character who is trying to make life easier not just for himself but for a community. He’s definitely very ambivalent about his position as an artist.”

The community Barrow will bring to life is stalked by two artists and collectors (two of Barrow’s own métiers), a garbage man and the serial killer following him and undoing all the public good he is trying to accomplish (drawings from the story appeared at Mercer Union in 2004 and Jessica Bradley Art and Projects in 2006). The music is by Linton of the band Aislers Set.

“The garbage man started this independently produced phonebook and the serial killer is a scrap craft artist who uses recyclable materials to make art. The serial killer is following the garbage man all night and murdering anyone he includes in his book, rendering his project obsolete. It was supposed to serve as this directory for a living community, and now it’s just become a sort of memorial.”

Originally the protagonist was to be a homeless person, a silent observer of traumatic nighttime events, who would restage them in miniature with trash, altering their original outcomes. Then the figure became a serial killer and the protagonist became a garbage man who creates peculiar portraits of his neighbours while they sleep. “I don’t know anything about actual serial killers,” Barrow says, “but I’m very interested in the serial killer archetype in the cinema, who almost always approaches his craft with an aesthetic, with a signature and with the ego of an artist. And so my serial killer is no different, he has a schtick, and he kills people with garbage.” Meanwhile, the garbage man’s attempt to covertly catalogue the community is reminiscent of Barrow’s own Winnipeg Babysitter project, wherein he curated a selection of his favourite moments from a Winnipeg public access television station into an impromptu collective portrait of his hometown via its minor stars, amateur performers and exhibitionists (it was presented at Images in 2006).

Barrow has been experimenting with juxtaposing video with his overhead animations for Every Time, playing with the registration of the two different kinds of light projection. But, for Barrow, good old drawing has been a form of storytelling since he was a child. “I’ve drawn all my life. I would spend hours and hours drawing by myself. But all of my drawing play was story-oriented so I would be telling stories basically exactly the same way my overhead performances function, and doing voices of various characters.”

The particularly morbid material in Every Time echoes some of the drawing games he played in his childhood. Barrow claims, for example, to have “basically invented” the concept for the reality TV show The Swan. “I would start with a fresh piece of paper and I would draw three eggs basically. Then I would put very minimal features on them, like chemotherapy hair. Then I would pretend that these were three insecure spinsters and I was the stylist. I would give them pep talks as I was applying their makeup and styling their hair with a ballpoint pen. And then when I was done, suddenly I was a beauty pageant judge asking them questions about themselves. And I had already predetermined which drawing I thought was the best — which was the prettiest lady — and I would draw a big crown on her head.”

An even more fiendish drawing game was called Torture. “I would be speaking the voice of the sadist and the victim. I would just be screaming and crying and then alternately mocking as I took this character through these different torture chambers. And then in the last room when I ran out of paper I would kill the victim, I would have him being chopped up into tiny pieces.”

Despite all these imaginary atrocities Barrow claims to have been too afraid to even look at the VHS jackets in the horror section of his local video store because he was “so scared of everything.”

“I even insisted up until the age of 14 that my baby brother sleep in my room to protect me,” says Barrow.

Part of why Barrow’s work is so affecting is how it channels all these appetites and obsessions, fears and humiliations of his queer boyhood — with his yen for drawing and collecting, TV and strange ephemera — through his fey voice and wry sensibility, rather than directly talking about “the gay experience.”

Barrow creates fantasy worlds with his drawings — in a grotesque and mannered style that evokes children’s-book illustrations — and there is something emotionally intense about witnessing him bring these worlds to life through animation projected large. His narration both lures us into the perverse, dreamlike stories, and draws attention to its own pretenses and artifice. As Barrow puts it, “[I try] to keep the piece personally volatile in a way. I guess if my performance doesn’t summon all my childhood shame and anxiety, it won’t seem particularly relevant to anyone in the audience, gay or straight.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra